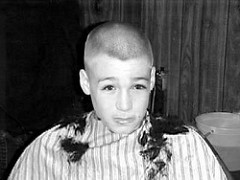

The late ’60s were exciting, turbulent times, especially for a young man growing up in a Catholic seminary. When I entered the Juniorate of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart in Pascoag, RI in 1966, there were 24 of us guys (most of whom were gay, I now realize), from all parts of New York/New England. We were the future of the Order, just as hundreds of young men who had come before us over the past half century. But something happened along the way–Vatican II, rock music, flower power, the anti-war movement, the political and cultural awakening enabled by the Beat movement and personified by the Hippie movement. That awakening decimated American seminaries, as religious candidates began to question their faith and tuned in to personal discovery and freedom. By my sophomore year, twelve of us remained; by my junior year, only 3. The Order, reeling from the loss of so many young and middle-aged brothers, shut down the Juniorate, sold off the property, and shipped the three of us seminarians to Woonsocket to attend Mt St Charles, one of the Brothers’ high schools.

There I began to reenter the secular world, going to school with regular local kids, and returning to the Brothers’ residence (a former hospital–my bedroom had been Minor Surgery, complete with blood spatters all over the ceiling) at night. During summer vacation after my junior year, I heard about the strange event called Woodstock, and shook my head in wonderment and confusion. When I returned to school in the fall, I remember vividly my friends recounting their adventures at Woodstock–they were profoundly changed by that experience, and suddenly the world had changed for me. I had had an aha! moment that changed the course of my own life. I quickly began to question my faith, all that I had been brought up to believe. Perhaps it was the times, because I very quickly shed the burden of all that Catholic weight from my shoulders–an epiphany of Paulian proportions.

And of course, my outward appearance began to change with the time. Even with the strict seminary dress code, I began to let my sideburns drop (like Neil Young’s), and my hair lengthen as much as permitted. By the end of senior year, I had donned a whole new perspective on life, as an idealist atheist, heading off to college to become a psychologist. As part of that new image, I vowed to let my hair down.

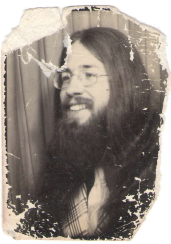

And just at the right time. The Boston of 1970 was a hotbed of antiwar protest and hippie culture, and I easily slipped into the student lifestyle. And, the music! The Beatles, The Stones, Cream, The Who, and King Crimson dominated the turntable in our dorm living room. And then Jethro Tull caught my attention–there was something about the English flute-folk sensibility combined with electric-guitar power that made me instantly follow Ian Anderson. Then and there, I vowed to grow my hair like my new hero.

And so I did, much to Mom and Dad’s chagrin. Dad would refer to me as my son “Jesus.” And Mom, who didn’t want me to go into the seminar at 14, now regretted that I had left, and was an atheist to boot! Mom had recurring happy dreams that I came home with my hair cut…

And so it went through college, all the way through graduation (see my attached booth photo right around graduation time). I had lived the hippie dream, as I had vowed. I wore a purple velvet suit (hand tailored by my talented teenage cousin) to my graduation dinner. And, when one of my parents’ friends approached me during the spring of my senior year about applying for a job with his organization–the CIA, I was aghast at the thought of having to cut my hair! You imagine correctly that the thought of working for the CIA was abhorrent, even immoral, and my prized hair remained unthreatened.

And so it went through college, all the way through graduation (see my attached booth photo right around graduation time). I had lived the hippie dream, as I had vowed. I wore a purple velvet suit (hand tailored by my talented teenage cousin) to my graduation dinner. And, when one of my parents’ friends approached me during the spring of my senior year about applying for a job with his organization–the CIA, I was aghast at the thought of having to cut my hair! You imagine correctly that the thought of working for the CIA was abhorrent, even immoral, and my prized hair remained unthreatened.

But of course, all things must change. After graduation, I took a temporary job managing TopCopy, a Xerox copy center, while I pondered my future. Not law school, not medical school, not psychotherapy, not an academic path…I gravitated instead to a career in public administration, and set about applying to masters programs.

To my good fortune, my terrific girlfriend had even more terrific parents who took an interest in my career. “If you’re interested in public management, why don’t you get an MBA with a public administration program,” they reasoned. Back then, business school was immoral to the Hippie world view, so that idea took some convincing. Thank god I listened to them, applied to business schools, and got into a dream program, just as they suggested.

It was time to grow up. Shortly after I signed my admission letter, I made the decision to cut my hair for the first time in five years. As my girlfriend accompanied me to the barber shop, my nervousness was only exceeded by the completely blase attitude of the barber. Quite a punctuation to mark the end of a life phase…