Wow, blue books! So many memories! I considered calling the story “Blank Space” — because there was always a lot more blank space than writing in my blue books — but figured this crowd wouldn’t know the Taylor Swift song, so I went with a 1970 song that applies equally well to my exam-taking experience.

At Harvard, many exams, especially in large survey courses, were given in a cavernous room in Memorial Hall, a High Victorian Gothic structure built in the 1870s to honor the college’s Civil War dead (but only those who fought for the Union). Lots of different exams would be going on in there at the same time, with students sitting at endless rows of long tables. The people sitting near you might or might not be in the same course as you. These exams always seemed to be proctored by the same man, who was known to all as Mr. Goodpeople, because he started every sentence with the phrase “good people.” So he would say, “Good people, you may open your blue books now,” then after almost three hours of silence, “Good people, you have ten minutes remaining,” and finally “Good people, close your blue books and put your pens and pencils down.” He spoke into a microphone, because the hall was so big that it was the only way everyone would hear him. It was pretty intimidating. When my son became a Harvard student, I was amused to learn that this cavernous exam room had been turned into the freshman dining hall, known as Annenberg, so I don’t know where they give exams now.

My worst blue book exam memory is from freshman year, from the most horrendous course ever given, known as Nat Sci 5. I took it to fulfill the one year of natural science that was part of the Gen Ed requirements. The fact that it was a single digit suggested that it was an introductory course, and the title was something about biology, which was the only science I had taken in high school. Unfortunately, it was neither introductory nor strictly biology. All the pre-meds were in this class, which should have tipped me off. After the first semester, I had a grade of C- and I could have dropped it then and taken a semester of some other science. But I knew there was a paper in the second semester, and I always did well on papers, so I figured I could bring up my grade. Big mistake! The second semester was heavily biochemistry, with amino acids, the Krebs Cycle, and god knows what else. I had never taken chemistry and I was totally lost. I did write the paper, and got a decent grade on that, but it wasn’t going to save me. So I went into the final exam with a sense of foreboding, and possibly a few amino acids sketched out on my hand.

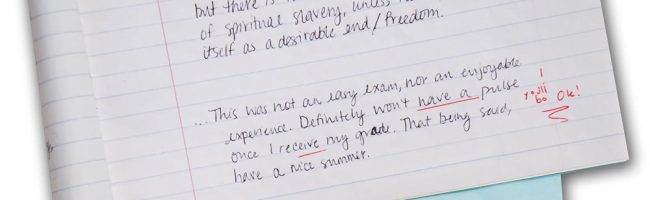

The exam had ten questions on it, each worth ten points. On seven of them, I didn’t even begin to understand the question and couldn’t possibly formulate an answer, even a BS one. The other three I actually did answer, possibly with the help of those sketches that may or may not have been on my hand. I also wrote a note in the blue book to the graders, begging them to pass me, because if I flunked the course I would have to take another year of Nat Sci, and that would probably cause me to quit school. We always put stamped, self-addressed postcards in our blue books so that we could find out how we did on the exam – otherwise all we would know was the overall course grade when our transcripts were mailed to us late in the summer. Soon after I got home, my postcard from Nat Sci 5 arrived, saying I had gotten a 29 on the final exam. I was elated! I had only answered three questions, which meant the most points I could have accrued was 30, and I had gotten 29 of them. That seemed pretty perfect to me – I should have gotten an A for how well I did on the questions I answered! What I actually got in the course was a D+, but that was okay with me, because it was sufficient to satisfy the Nat Sci requirement and I was done with science!

My next blue book memory is from a course called Soc Sci 137. It was a general education course about the law, taught by Paul A. Freund, who was a professor at the law school. It was a hugely popular course, with hundreds of students in it. A good friend of mine, also named Paul, was taking the class with me, and when we were preparing our stamped, self-addressed postcards to put into our blue books, he wrote on his, “It was a great experience having you in my class, PAF.” This was obviously a joke, to make it look like he had received this flattering message from the great Paul A. Freund. I thought that was a funny idea, so I did it too. When I got my postcard back, there was another note written under mine saying “I hope it was for you, PAF.” I have no memory of what grade I got in the course, but I was pretty jazzed to get a handwritten note from Freund! I looked for that postcard to illustrate this story, but alas, it must have gotten lost at some point in the last 50 years.

My final blue book memory is from my first exam at UC Davis Law School. UC Davis started out as an agricultural college, and the school’s nickname is the Aggies. When they passed out the blue books, I saw that the honor code was printed on the front, along with a statement saying that we would neither give nor receive aid on this exam. I didn’t have a problem with promising not to give or receive aid. My problem was that the statement we were signing started out “I, _________________, a California Aggie, promise . . . .” You were supposed to print your name in the blank and then sign at the end. I was a city girl, and didn’t like the idea of calling myself an Aggie. I wanted to put in my name and cross out “a California Aggie,” but in the end I left it. I didn’t want the professor to be biased against me when he was grading the exam.

I would have thought blue books would be obsolete now in the computer era, but apparently colleges still use them. I guess they can’t let students bring their laptops into an exam. Even if they turned off the WiFi, the kids could have all the answers stored on their hard drives.