I am reposting the story I wrote for the prompt “Gratitude” two years ago, with updates. I decided to do it this way, rather than just move the old story to this prompt, because this will be my 100th story! Thank you for your indulgence.

***

Thanksgiving was always the most special holiday in my family when I was growing up. It was the one time of the year when everyone would gather, aunts and uncles and cousins, to spend the day together, eating and talking and enjoying each other. It was the only time all year that we ate in the dining room instead of the kitchen, putting all the leaves in the table so it would seat everyone. It was also the only time we used the good dishes, a delicate Wedgwood bone china that my parents had bought on a trip to England. We would have hors d’oeuvres in the living room first. Olives, marinated mushrooms, smoked oysters, and other delicacies, with brightly colored toothpicks to spear them all. I first tasted smoked oysters as a child on Thanksgiving, and I have loved them ever since.

I’m not sure if we ever talked about politics at the dinner table. It’s possible that we did, especially during the Vietnam Era, but I don’t have any recollections about it. Even if we had, there wouldn’t have been much arguing, since we all had essentially the same political views. It may have taken my father a little longer to get to the point of thinking the war was wrong, but I know he got there, and I don’t remember any trauma related to it. The only family member with a totally different political view was my uncle Ed, who was a rabid pro-Soviet communist. In his eyes, the Soviet Union could do no wrong, to the point where he wouldn’t admit that there was any anti-Semitism there. He even went to Moscow every spring for the Mayday celebrations. But for the most part, nobody engaged in argument with him. Except for once. I was in college, taking a course about China, and totally smitten with Chinese communism, which was at odds with Soviet communism at the time. He and I had an argument about which was better. But it wasn’t at the dinner table, it must have been before or after. Neither of us convinced the other, but I don’t think there were any hard feelings.

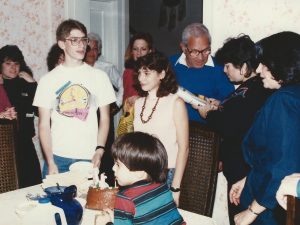

The last of the consecutive family Thanksgivings we had, where everyone in the entire extended family showed up, was in 1977, when my niece, the first baby of the next generation, was six months old. After that it seemed to be too hard to gather everyone at that time of year. Twice thereafter my parents and sisters and I gathered at my middle sister’s house in Colorado, but it didn’t include the cousins. Two decades later, in 1999, we had one more Thanksgiving gathering of everyone, because my nephew’s bar mitzvah was that weekend, so we stuffed ourselves with turkey on Thursday and danced the horah on Saturday. Later on, during the years when my two older kids were in college on the East Coast, and it didn’t make sense to fly all the way across country for four days, they went to my oldest sister’s house in Brooklyn for the Thanksgiving vacation, and my mother was there too, and the other members of the Eastern branch, and I was very thankful that they still got to have a family Thanksgiving even if I wasn’t there.

Now my extended family gets together in the summer rather than in November, because it works better for everybody’s schedules, but I do miss having everyone together for Thanksgiving. I am thankful that two of my children still come home to Sacramento for Thanksgiving. The one who doesn’t come has a good excuse, as she lives in Spain where it isn’t even a holiday. The other two have an easy one-hour hop from LA, and this year they are even on the same flight.

***

At any time of year, I am grateful to have the family I do, both the one in which I grew up, and the one I have formed as an adult. Each member is a loving, thoughtful, intelligent person with whom I enjoy spending time. I have been particularly thankful for the last two years that we all share the same political views. I know that many of my friends have relatives who are Trump supporters even now, and I can’t imagine how that would be, and how one could have a civil conversation with them. The midterm election two weeks ago was such a relief, especially as more and more Democratic wins trickled in, and it’s nice to be able to share the elation with all of my family members. And the fact that one family member is in the forefront of the fight against Trump makes it particularly sweet!