Is spelling skill genetically determined? If so, where do the spelling genes reside in our DNA?

Read More

Spelling: Nature vs Nurture

Is spelling skill genetically determined? If so, where do the spelling genes reside in our DNA?

Read More

Experiences in volunteering in, especially in youth soccer and Kiwanis.

Read More

As the story goes, the property on Valencia Street was zoned for retail. But the new tenants wanted to open a tutoring center. Naturally, the solution was to start stocking up on pirate stuff.

The Pirate Supply Store at 826 Valencia is really a front for a place where kids in San Francisco can get help with writing and homework. In 2002, when I was working as a college advisor in a Bay Area high school, I read an article in the San Francisco Chronicle about this brand new tutoring center in San Francisco’s Mission District. It sounded like something I might like, so I called and went in for an interview.

From the website: “826 Valencia was founded in 2002 by educator Nínive Calegari and author Dave Eggers. The idea was simple: they wanted to support overburdened teachers and connect caring adults with neighborhood students who needed a little help with their writing.”

My experience with rising seniors and their struggles with personal statements seemed tailor-made for 826 Valencia’s needs and I became part of the first group of volunteer tutors to sneak past the eye patches, hook protectors (corks), drawers full of X’s (to mark the spot on treasure maps), and a large barrel full of lard, among other things, to the back area where tables and chairs were set up for students.

It was exciting to be part of this new adventure, and I met the most amazing, dedicated people who ran the place. I went to high schools on field trips to help kids get started with writing their essays. And classes of kids came from across the Bay to 826 on field trips to get help with their writing. For most kids, this meant taking BART to the Mission and walking through the eclectic neighborhood to the pirate supply store/tutoring center. A few years into my tutoring stint, 826 began offering a Personal Statement Weekend at Mission High School. Students from all over the city came with drafts of their essays and were paired off with volunteer tutors who had attended a training session, often led by me. I loved working one-on-one with the kids on those weekends. They all came with such interesting stories, even though they may not have thought they were interesting at all.

On one occasion, we were visited by a group of middle school kids who were writing essays about a book they had read. One of “my” kids sat slouched in his chair, chin in his hand, eyes half-closed–not exactly the picture of readiness for a stimulating discussion of his work. He had chosen to write about All Quiet on the Western Front, a story about young men not much older than he, fighting in World War I. I read his first paragraph and stopped in my tracks when I got to this sentence: “They made lifelong friendships that didn’t last very long.” I looked him in the eye and said, “This is one of the best sentences I have ever read. Really.” He sat up then and smiled. It was a moment for both of us.

Another great aha moment: working with a kid who did a compare and contrast essay about his life and The Simpsons. You just never know what kids will come up with when they get some encouragement. This kid ran with it, and produced a unique essay about life in the inner city set against the crazy TV world of the Simpsons.

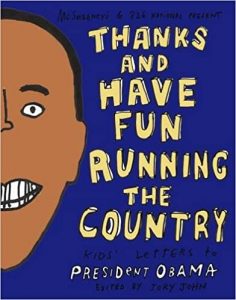

The good folks at 826 Valencia produced many books of student work. Jory John, one of the talented staff members who has since become a best-selling children’s book author, pulled together letters to then President Obama to create a book of helpful advice from kids. Obama was spotted carrying a copy of it!

826 Valencia (which now has nine official chapters nationally, all called 826) also published a book called Don’t Forget to Write: 54 Enthralling and Effective Lessons for Students 6-18. Jenny Traig, writer and editor, asked me to contribute a chapter for the high school section. So, there I am, on the same page with some kick ass writers. I was thrilled to be asked and so excited to be a part of this work.

826 Valencia (which now has nine official chapters nationally, all called 826) also published a book called Don’t Forget to Write: 54 Enthralling and Effective Lessons for Students 6-18. Jenny Traig, writer and editor, asked me to contribute a chapter for the high school section. So, there I am, on the same page with some kick ass writers. I was thrilled to be asked and so excited to be a part of this work.

My years with 826 Valencia finally came to an end after over 10 years and 100 plus hours of volunteering, and a collection of cool 826 swag. I tapered off, only going to the personal statement weekends until my fall travel schedule started to interfere.

I have to say that working alongside other dedicated volunteers and carrying out the mission of the amazing duo of Dave Eggers and Ninive Calegari was one of the best things I’ve ever done.

I found myself talking during naptime one day to Rosita, the Urban Court staffer whose job was to conduct outreach for the new program. I started asking her a lot of questions and soon found myself recruited to the training.

Read More