“What do you remember about Watergate?” asks this week’s prompt. I am finding it a very difficult question to answer. Right now I could tell you everything that happened from the night of the break-in at Democratic Headquarters on June 17, 1972 (two days after I graduated from college), to the resignation of Richard Nixon on August 9, 1974. But how much of it do I actually remember from when it happened and how much do I know from books and movies? It’s really hard to say.

I read the book All the President’s Men shortly after it came out in February 1974, and learned about a lot of what transpired from Woodward and Bernstein. Of course much of what we now refer to as Watergate is not even in that book. It only includes events through the revelation of the tapes by Alexander Butterfield (July ’73) and then a brief mention of the Saturday Night Massacre in a hastily-written last chapter. I have also read other books about Watergate over the years which have certainly supplemented my memories.

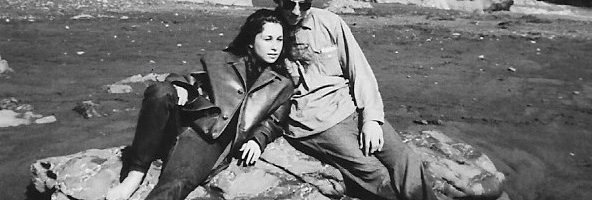

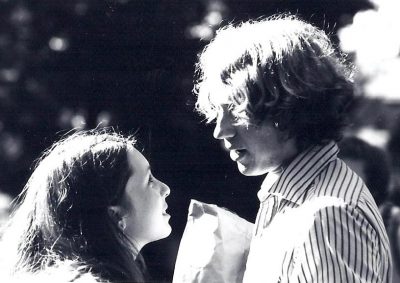

I do remember Archibald Cox being appointed special prosecutor in May 1973. The previous year he had been my college boyfriend’s thesis advisor. My BF and I had met in a junior tutorial on the Supreme Court (’70-’71), in which we actually read Supreme Court cases and wrote papers about them. An American Government concentrator, I had already studied the American Presidency as a sophomore, and requested a junior tutorial on either Congress or the Court. What I wanted was to learn about the Court, not take a mini-Constitutional Law course, but that was how it ended up. In truth, the best part for me was the one other student in the tutorial, a smart and handsome swimmer from Adams House who soon became my BF. The next year (’71-’72), while I wrote my thesis on the McCarthy presidential campaign, he wrote his on Congressional power under the 14th Amendment. When he went to ask Cox to be his thesis advisor, he was dubious about his chances for success, but I think Cox was intrigued by this undergraduate who could speak more knowledgeably about the law than most of his law students. My BF got a summa on the thesis, so obviously Cox did a good job of advising him. They spent a lot of time together, and I felt connected by association. A year later we were both excited by the special prosecutor appointment. By October ’73, when Cox was fired in the Saturday Night Massacre, my BF was at Oxford on a Marshall Scholarship, and I was still in Cambridge (the other Cambridge, as they say in England), but we wrote letters to each other about it.

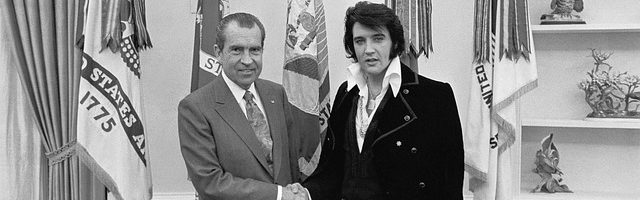

During that whole period I was working for the US Department of Transportation at their Systems Center in Cambridge, and every day as I walked in I saw the big pictures of Richard Nixon and John Volpe on the wall in the lobby. The reason DOT even had a facility in Cambridge was that Volpe, Nixon’s Secretary of Transportation, had previously been Governor of Massachusetts, and he wanted this pork barrel project for his home state. Most of the people I worked with were either Republicans or apolitical, so there wasn’t much talk about Watergate at work.

I was living in a wonderful old house on Cambridge Street (shown in the featured image) with three roommates. Arlene, the roommate I was closest to, was a graduate student in sociology at BU, working on a dissertation about people who wanted to have their bodies frozen when they died. When I consulted her this week about her memories of Watergate, here’s what she said: “I remember that summer [of 1973] sooo well. I was transcribing the interviews for my dissertation all summer. I had a piece of wood across cinder blocks and an electric typewriter. The Watergate hearings were on in the background all day. I filled you in when you came home and then we watched whatever was rebroadcast on the small tv in my room. I’m pretty sure you were home from work in time to watch the evening network news. [I was.] The tv was a portable one and couldn’t have had more than a 12 inch screen. As I recall, I had a window air conditioner and a bright orange rug, so the viewing was comfortable. That all seemed so catastrophic then, but pales now in the age of Trump. Ugh!!”

I remember being impressed with Sam Ervin, the chair of the Senate Watergate Committee. He was from North Carolina, and presented a very folksy demeanor, but was obviously smart as a whip and did a great job of running those hearings.

I also remember being impressed with Peter Rodino, the chair of the House Judiciary Committee which oversaw the impeachment proceedings. He began his investigation after the Saturday Night Massacre, and meticulously spent eight months gathering evidence. He was my congressman, in fact had represented my New Jersey district since before I was born. When I visited Washington during high school and got gallery passes to watch Congress in action, the one for the House came from Rodino, and I met him then. I voted for him in 1972 at home, and in 1974 by absentee ballot, before changing my voter registration from New Jersey to California.

Finally, I remember watching Nixon’s resignation speech on Thursday, August 8, 1974, at 9:00 p.m, again on Arlene’s little television set. The resignation was effective at noon on Friday, which I think was also my last day at DOT. So Richard Nixon and I left the federal government at the same time, although for opposite reasons — he because he had broken the law, and I because I wanted to study law.

There is much that could be said about how horrified we all were forty-four years ago, and how evil we thought Nixon was, and how he now seems positively benign compared to the present occupant of the White House. However, I will leave that to others.