Accounting was just add-subtract-multiply-divide, right? Apparently not.

Read More

Left Brain or Right Brain?

Accounting was just add-subtract-multiply-divide, right? Apparently not.

Read More

Shy people often come alive through acting. I was no exception. Though a skirt-hugger as a little girl, I started singing publicly as a 7 year old, and acting at about the same time. Everyone thought I had some talent and I was encouraged to pursue it. I was passionate about it. With the stage lights blinding me, I could become someone else and escape into some fantasy world, explore new places and facets of myself, get away and be someone else.

Though I could move well, I felt awkward and from the time I got glasses at the age of 8, I went through a serious ugly-duckling phase. My beloved second grade teacher discovered I had a knack for voices. I could cackle, so when we read fairy tales aloud in class, I would read the witch or old lady. Mrs Zeve had been a “radio” major in college (I think today we’d call it communications) and she encouraged her shy charge to voice other characters. She proudly came to see me play Gretel in the all school (K-8) production of “Hansel and Gretel” when I was a mere 5th grader. We moved out of Detroit that year, but I didn’t lose touch with Mrs. Zeve. The one photo I have of her was after a high school production of “Arsenic and Old Lace”. I played Elaine, the love interest. My mentor died the next year at the age of 42. She never knew that I went on to be a theatre major in college.

I spent six glorious summers at the National Music Camp (now the Interlochen Arts Camp) in Interlochen, MI during the ’60s, majoring in voice and drama, also taking dance. I sang in the chorus, took Operetta, and had good parts in the High School dramas, culminating in the role of Hermia in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” in 1969. Though not a strong enough singer to ever have a lead in the operettas, the director always gave me extra acting bits to do and rewarded me with the Operetta Chorus Award the three summers I was in the High School division, even going so far as to name me the best female chorus member for the first 25 years of Operetta of all time at the camp!

I was more determined than ever about my craft, got all my general curriculum requirements out of the way during Freshman year at Brandeis and honed in on theatre, which at the time had an excellent theatre program, with a strong graduate program and would hire many professional actors to come in, take leads in the productions and teach part-time in the studio classes.

I began with small parts in large main stage plays and other parts in plays directed by the grad students. For my “tech” requirement, I began stage managing. I was good at it.

By sophomore year, I had a lead in the Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. Junior year, I won the coveted role of Sarah Brown in “Guys and Dolls” against a large field of grad students. The director said he wanted “a little dynamo”. He hired a professional in his mid-40s to play opposite me in the role of Sky Masterson (the role played by Marlon Brando in the movie). Jack had a beautiful singing voice, but needed a hair piece and girdle to go on-stage and look somewhat appropriate. We were an odd couple. He was hardly believable as the dashing gambler who sweeps me off my feet, takes me to Havana on a bet, but actually falls for me. I know…this is ACTING.

The director didn’t help. His directions were mushy. Ultimately, I felt I gave a better first audition than final performance. It is not supposed to be that way. The reviews came in and I never forgot them. The Worcester Telegram said, “Elizabeth Sarason is a superb Sarah”. Boston After Dark wasn’t as kind. “Elizabeth Sarason plays a passing flirtation with the correct key. She acts better than she sings and looks better than she acts. Enough said.” I was devastated. Except for a dancing/acting role in a friend’s senior honor’s project (“An Evening With Garcia Lorca”) and the role of Clea in “Black Comedy”, I have not been in a show since. I am not thick-skinned. I did not have a strong enough drive to overcome the rejection.

I became one of the top stage managers at Brandeis. Senior year, I stage managed the complicated show “Lenny”, for which I was awarded departmental honors.

“Two roads diverge in a yellow wood, and sorry I could not travel both”. Robert Frost wrote “The Road Less Taken” 100 years ago. Randall Thompson turned it into a popular song that I first sang at camp as a 13 year old and as recently as last May in my current chorus. I did not continue with acting, but did with singing, another form of artistic expression which continues to offer gratification. I have thought about roads not taken, both in pursuit of life achievements and love life and what might have been. But one can’t dwell on those thoughts…the “what if’s” or “what might have beens”. One lives life one day at a time; moving forward.

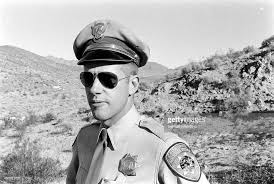

He nodded the beak of his perfectly molded, authoritarian-style trooper’s hat in my direction.

Read More

I confess to hitchhiking once. I don’t think my parents ever knew.

Read More