We were driving north up Interstate 80 from the East Bay to Davis, California. We had a show to do at UC Davis with a ragtag street theater group called the East Bay Sharks. I was driving a pickup truck with a hand-made redwood camper securely fastened to the truck bed. The camper was very well made and good looking. Built of resawn redwood plywood, it sported diamond-shaped windows, a skylight, and a fancy, hand-carved scroll of flames over the rear entrance, hewn out of the redwood ply. A stiff, green canvas flap covered the back, affording a modicum of modesty to its passengers.

He nodded the beak of his perfectly molded, authoritarian-style trooper’s hat in my direction.

Clyde and I, the crew of this erstwhile land cruiser, were not as well-made or good-looking as our vehicle but, boy, could we play music, all manner of tunes, from Old Timey to jazz to R&B. I played the guitar and Clyde played bass for The Sharks. We could sing, too, and the company wrote its own songs, like “Angel of Fire,” a doo wop creation celebrating the dry-ankled wisdom of Noah, the flawed protagonist of an epic cartoon story depicting the flood, not such an immediate subject as it is now.

So there we were, cruising up Interstate 80 when a piercing red glow lit my side-view mirror. It was a familiar glow, a red orb of flame, the hairy eyeball of the California Highway Patrol, circa 1969.

“Dammit,” said Clyde.

My heart began to pound, my mouth went dry, and my hands began to shake. Back then, the CHP, especially in the hinterlands, was inspired to authority by the sight of any vehicle that suggested resistance. The redwood camper must have made the trooper salivate. There be hippies up ahead.

“What do they want,” Clyde asked.

The mirror glowed redder, reflecting blood into the cab.

“Papers in order?” Clyde was an original hipster with a colorful musical background, having played bass with the Chicago Symphony and acting as sideman to the doubly hip and charming blues pianist and lyricist, Mose Allison. “I’m too old for this shit,” he murmured as I rattled the truck onto the gravel verge.

My papers were not in order. For reasons too lengthy to describe, I had earlier bid farewell to the Bay Area, shedding my identity along the way. I now had a Colorado driver’s license in the name of Stephen Django, a moniker hastily cobbled together thru associative thinking. The Stephen name, sans an “e,” tipped my hat to the iconic French jazz violinist, Stephane Grappelli. My surname I took from Mr. Grappelli’s Parisian partner, the extraordinary, three-fingered jazz virtuoso, Django Reinhardt.

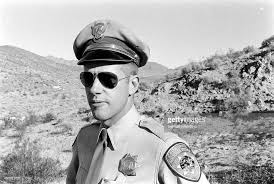

The CHP guy appeared at my window, looking red-faced and surly. It was hot out there in Dixon, wherever that was. I know we were near Dixon because I had stopped before the big green freeway sign that shouted Dixon! to all who whooshed by. We weren’t whooshing by, Clyde and me.

“How can I help you, offi…”

“License and registration.”

Not even a “please.” My mind spun. My license bore Django’s name but the truck was registered under my girlfriend’s name, to avoid any collision between identities.

Clyde moved to open the glove compartment.

“Not you,” the Land-O-Dixon trooper growled.

Clyde glared at me, then sat back and folded his big, bass-player’s hands in his lap.

“You.” He nodded the beak of his perfectly molded, authoritarian-style trooper’s hat in my direction.

I reached across the gearshift lever and over Clyde’s girth, opened the glove compartment, grabbed the registration. Then I froze.

From the passenger-side window, timid eyes peered at me from beneath a dusty mop of thick, blond hair.

Trooper bad-ass stepped back from the truck and unsnapped his holster flap. “Step out of the vehicle,” he shouted. “Now!”

I opened the door and stepped out, my heart pounding.

Clyde couldn’t figure out which way to look — at me, the dusty kid, or the highway patrolman.

“You, kid,” CHP growled. “Where did you come from?”

Clyde snarled at the kid, unholy as ever. “Yeah. Where the hell DID you come from?”

“You, in the passenger seat. Shut up and put your hands on the dashboard. “

Clyde complied.

To the kid, the cop said, “go around the back and stand where I can see ya.”

The kid’s eyes widened and he disappeared. I could hear his feet crunch on the gravel verge.

I turned to The Man. “Sir, I’ve never seen that person before.” Oh boy, I thought, did that ever sound lame or what.

The cop grabbed my bicep and shoved me to the back of the truck.

The hot valley sun beat down and cars slapped by, impassive, tires whining on the tarmac.

“You say you never saw this kid before?”

“No sir. I sure haven’t.”

“So where did he come from?”

The kid pointed to the green canvas flap, looking at me all sheepish.

I felt my eyebrows knit.

“You been riding in there,” the cop asked.

“Yessir.”

“Really, officer, I had no idea. I…”

“Shut up.” The cop pulled back the tarp. Nestled in the gloom was Clyde’s big bass, my guitar, a snare drum, a rolled up East Bay Sharks banner, two rolled up sleeping bags, and a little girl, fifteen-ish, clad in a cruddy Mexican sweater and blue jeans, her dirty feet slipped out of worn huarache sandals. She had her sweater sleeves pulled down over her fingers, her fingers crammed into her mouth, and she was crying.

I looked at the kid. “How did you…?”

“We got in at the gas station, back there.”

“Miss,” The CHP guy sounded weary. “Please step out of the vehicle.”

The little girl crawled out, weeping, tears streaking her dusty cheeks. She stood beside the guy, knock-kneed, sucking on her sweater.

“We’re just trying to get to my mom’s house,” the guy explained.

“Where?” The cop asked.

“Just outside of Sacramento,” the guy said.

“We want to go home,” the girl said.

Clyde joined us at the back of the truck. “What’s happening?”

The cop looked at Clyde, the kids, the back of the truck, and at me. He pulled the canvas aside a second time and nodded to the kids. “Get in.”

“I’m sorry, officer,” I explained.

The cop put up his hand. “Stop. I don’t want to hear another damned word out of any of you. I’m gonna pretend I never saw any of this.” He swept the green canvas across the back of the truck, glared at me one more time, and walked away, bringing down the curtain on a roadside tale of broken stereotypes and serendipitous empathy.

Hitchhikers? No. Stowaways. I guess.

We stopped at the next roadside gas. I tried to reach our compatriots from a phone booth, but nobody at the university switchboard knew a damned thing about any East Bay Sharks.

Clyde and I drove the kids home and the East Bay Sharks did the show without us.

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.