Then someone said, "You guys get up there." Bud and I looked at each other. Why the hell not?

Read More

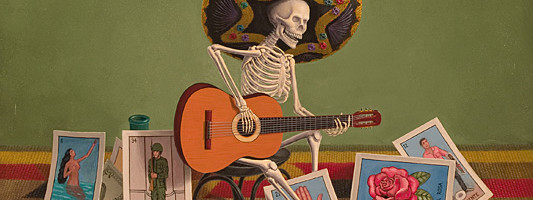

El Año de los Muertos

Some say death can be your ally. Yeah, maybe…

If you’re an Inuit shaman or a Yoruba priestess. Some days I can dig it. Mostly I doubt that death teaches us anything.

Today marks the year-one anniversary of ZL’s death. I first met Z when she ran into a theater rehearsal and shouted “they’re gonna put artists on a salary!” She was right. For five years, hundreds of us — filmmakers, theater artists, muralists, musicians — collected a paycheck and benefits for doing art in America. Impossible? No. Thanks to Z, we all applied for the program. Oh, the stuff we accomplished.

ZL lived in a Northern California commune through her 20s. We’re talking serious close-to-the-land self-sufficiency with a righteous point to make — this system sucks; we’re gonna build a better one. If you don’t mind wood stoves, kerosene lanterns and outhouses, they succeeded. When she returned to San Francisco, Z lived on Dolores Street in a rangy pullman apartment that logged in more traffic than the Bay Bridge.

I knew Z best from working with her in the Pickle Family Circus. I put the band together, Z did advance work (we toured a lot), juggled, and worked as a roustabout. Boundless energy, stubborn positivism, and gallons of coffee gave the woman superhuman powers. When stricken, Z didn’t appreciate her condition; it pissed her off to be dying. No apparent lesson to be learned there.

HM was the next to go. He was one of my few male friends in Los Angeles. Guys. Most of them don’t age sociably. HL did. He was an exquisite guitarist and songwriter born in Boyle Heights when the community integrated — half Jewish, half Chicano. H was half Jewish, half Chicano. Brooklyn Avenue became Cesar Chavez Avenue and everybody in the ‘hood thought it was cool.

HM told amazing stories, had a great sense of humor and made me laugh, showed me where to buy the best guitar, get these special strings. H could play anything. We both sang and sounded great together, rarely rehearsed. We already knew the same tunes. We could play “Don’t Think Twice” as a polka and make it swing. H bailed because the cure grew worse than his disease. Lessons? H was wiser, funnier, and a better musician when he was alive. Dead, he’s just not here anymore.

HR played tenor and drove a cab. Born in Detroit, H split after college, came out to San Francisco. All time I knew him (decades), H wore a perennial beard and a black Greek fisherman’s hat.

I met H in Winter Sun, my first electric band. He came across to play with us in the Pickle Family Circus band. He was the calmest adventurer I’ve ever known. He’d say ‘why not’ and try anything. H loved jazz, his friends, and marijuana until he dropped it. He excelled without need for recognition.

When H learned what assaults he would have to endure to gain a few more months, he said ‘no thanks.’ His decision seemed very much in character. I guess that means he died the way he lived.

DL was my oldest friend. We rambled, raced, rocked and rolled together from fourth grade through high school. D was born in the UK but emigrated when his old man, a British colonial attache in North Africa and graduate of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, decided he could not tolerate the socialist disaster that befell his precious bloody England when they booted Churchill out of Number 10 Downing. DL’s dad snatched up his wife and child and fled to our small Massachusetts town.

DL was smart but unpopular. His unorthodox intelligence suffered from the censorship of traditional education and an intolerant township elite. D grew to be an inspired liar and learned how to not give a damn. He did not-give-a-damn well, even flamboyantly. According to the club, D had already boarded the train bound for purgatory. I always liked the guy. We hung out in high school and I don’t think he ever crossed me.

I lost track of D after high school. After my old man died, my mother moved away and I lost track of everyone in that little town. David and I picked up at our 40th high school reunion, the first we had ever attended.

DL may have gone to purgatory, but he returned as a fabulously rich man. He restored a house on the water in Duxbury with a ship chandlery from 1820 still outfitted in the back room. A vineyard ran down a gentle slope to Cape Cod Bay. He refitted an elegant, seaworthy 70-foot, ketch-rigged schooner from the Gilded Age and built a hilltop palace on St. Lucia.

DL and I had reached two different destinations, often traveling the same paths, but not together. I had been a revolutionary, D a hippie entrepreneur. We disagreed on everything. We didn’t give a damn; we loved each other unconditionally. I barked back at his smart but cynical worldview. He understood and supported my writing, the worlds I choose to explore. I marveled at the generosity of his extravagance.

D only shined me on one time. He told me he was fine when he wasn’t. He told me not to bother visiting him, he’d be back on his feet by summer. In reality— like HR — DL pitted the cure against the cause and the cure lost. All I learned from DL’s death is how much I miss him.

- * * *

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe death can be an ally, a mentor. It’s certainly a reality. But as the losses increase, life begins to feel like war. And — as with war — there are no lessons to be learned from death. Perhaps I’ll learn something after the fact. In the meantime, I love life too much to seek instruction.

# # #

Modern Dance Lessons

Looking back at modern dance lessons in Manhattan, and the drive through the Holland Tunnel to get there.

Read More

Shy Child

I was so shy, I was a skirt-hugger. I loved to play with my dolls, the kids in my neighborhood and was dazzled by the performing arts. My first love was ballet and I started lessons at the age of seven. With flat feet and a sickly constitution, I wasn’t very good, and often missed class, so despite being quite musical, my mother pulled me out of class, though I did get to see my teacher as the Sugar Plum Fairy in a local production of The Nutcracker Suite. I was hooked, though didn’t get back to lessons until an adult.

I took requisite piano lessons in 5th grade but watched The Mickey Mouse Club instead of practicing. I was, however, showing a talent for singing. When my parents’ friends came over, I was trotted out to sing Broadway show tunes, which my mother taught me when I was very young. I would sing “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” full blast on my swing set to summon my best friend/next door neighbor to come out to play. I knew quite a repertoire of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Lerner & Lowe songs at an early age. But I was a misfit at school; smart, qawky, with glasses and buck teeth. And a bad hair cut. At about this time we moved from Detroit to the suburbs and things got really bad socially.

In the summer of 1964 I began attending the National Music Camp in Interlochen, MI (now the Interlochen Arts Camp) as a drama and voice major. There I fit in completely and made the friends of my lifetime, both in the cabin and in the classes I took. One counselor and one teacher made a lasting difference in my life.

My counselor in 1966 was Marilynn Andersen, universally called “Grundy” for reasons that were never clear to me. She was a warm, gregarious person who taught friendship by example and played a great folk guitar, prompting boisterous songfests. I was still quite shy and unsure of myself, as many 13 year old girls are. Grundy’s infections good humor and compassion allowed me to blossom. Eight weeks can make a lifetime of difference. In her train letter to me (an end-of-the summer ritual, written to each person in the cabin to amuse her on her way home; I obviously still have the one she wrote to me 50 years ago), she said: “An excellent camper you’ve always been all along, and you truly are a virtuoso in the the art of living. Keep your sense of humor, enthusiasm, and intelligence always about you, and you’ll never ever lack for friends.” No one had ever said that to me before. It is not an overstatement to say that going forward into high school, I developed a certain self-confidence that has stood me in good stead ever since.

The next summer, in High School Division, I was able to take Operetta with Clarence “Dude” Stephenson. I had taken it as an Intermediate, but the High School production had really serious singers and a huge chorus, frequently as many as 90 girls. The leads had wonderful voices, some went on to real careers in opera and inspired me to take voice lessons when I returned home. But I was never of the calibre to get a lead role in Dude’s Operetta (always a Gilbert & Sullivan, fully staged with costumes rented from Tracy & Co in Boston…always a highlight of the summer). But I am just five feet tall, and was a Drama Major. Dude would line up the chorus by height, so I always led the chorus on and off the stage and he would give me special bits to do, knowing that I would be fully in the moment and could carry it off. And he rewarded me by singling me out to win the Operetta Chorus Award all three summers that I was in the division, and as the best Female Chorus member for the first 25 years of Operetta at camp. The first year I heard my name called was surreal. I sat there, not at all expecting the honor and heard “Elizabeth Sarason”. No one calls me “Elizabeth”…ever. So I sat there, thinking the name was familiar, but it couldn’t be me, not little Betsy. Everyone was looking at me. And suddenly I realized it was me. From a group of 90 girls, I was singled out. I had been noticed. And I learned that as individuals we DO make a difference. We do the best we can, we put our hearts into whatever we do and our efforts are appreciated. We are not all soloists, but being part of the ensemble is just as important. I learned that from Dude.

I went on to have a successful career in tech sales, which takes a willingness to get up in front of people and follow through with strangers. And Dude and I remain friends to this day.