One day, an odd-looking bus pulled up in my French Canadian ghetto, near the corner of Kinsley and Liberty streets...it was labelled "Bookmobile!" This was to be my weekly oasis, my ticket to reading freedom, for much of my childhood.

Read More

Sputnik

We lived at the edge of a forest in Massachusetts. The hay field across the road served as a planetarium surrounded by stone walls and maples. From there, the night sky unfolded for us: an unusual moon, the northern lights, an eclipse, but now. . . who could predict?

“Tonight!” My old man shouted. “Sputnik! It’s going to orbit right over our heads. We’ll be able to see it.”

“I thought it was the size of a basketball,” I mumbled. “How’re we gonna see it?”

“It’s a sphere,” my old man said. “It magnifies reflected light.”

“Come on,” I said.

“Look it up. Plug in the ratio of lumens as a function of sphere circumference and distance. . .”

“Distance?” I grumbled. “Distance to what?”

“In this particular situation, my boy. . .” My old man liked to imitate W.C. Fields, Groucho Marx, Jack Benny. That night he was W.C. Fields. “The distance from satellite to earth and sun to satellite, the circumference of the sphere. From our vantage point (nobody said POV back then), it should look like an orbiting Venus.”

“Won’t that be lovely,” my mother chimed in. “Venus. Like Botticelli, in that clamshell, for the whole world to see.” My mother was an exhibitionist.

My old man pushed away from the table. He lit the sticky-sweet, cherry-stink tobacco in his five-dollar, Huckleberry Finn, corncob pipe and gazed up at the darkening sky. “For the whole world to see.”

Most people looked upon the unblinking mini-moon as a threat. The Soviets had shot the damned thing up there with a super-powerful spaceship, proving they could send anything anywhere. The Ruskie satellite orbited the heads of humans worldwide, a lighthouse for the devil. “If the commies can do that,” our authorities told us, “they can do whatever they want.” They would then elaborate, giving specifics about whatever aspect of the communist threat was being featured that week.

“Paranoid bullshit.” A backhand flick of the wrist dismissed the partisan fears. My old man was beyond all that. “Give it time. That little ball is going to unite the world.”

Now the family stood in the meadow gazing upwards into the sprawled bowl of stars. Would Sputnik drift? Would it float? Would it crawl so slow as to render its orbit imperceptible, the way the planets sidled across the night sky? Or would it fail, descend, and burn out like a meteor?

“There!” I shouted, my voice adolescent and shrill. A small orb, gleaming with mercurial clarity, broke over the treetops from the east and glided, slow, smooth, and silent across the cold New England sky.

“Jiminy!” my mother said.

“Just like a tiny Venus,” my sister said.

“That’ll make the Pentagon crap in its pants,” my old man said.

Amid Cold War infestation, my old man managed to impart a love for the patterns and structures and physics of astronomy in his son. Despite my resistance, my father’s spiritual, non-religious enthusiasm for the music of the celestial spheres had infected me with curiosity about the world, the planets, the solar system, the galaxy, and how the entire fucking Universe might operate.

I thought sputnik was beautiful beyond belief.

# # #

Roger and His Calvins

Craig gained additional notoriety in 1990 when he appeared in newspaper ads modeling Calvin Klein briefs—and nothing else.

Read More

Moon Reflections

The moon has a spell-binding hold on our collective imagination and never more-so than the summer of 1969.

That summer was my sixth and last summer as a camper at the National Music Camp (now Interlochen Arts Camp) in Interlochen, MI, the granddaddy of fine arts camps, set in a pine forest between two lakes in northern Michigan. All the girls divisions, as well as most of the main performances buildings at the time were set on Lake Wabakanetta, including Kresge, where the Gilbert & Sullivan operetta was performed, and Grunow, where the High School division put on its plays.

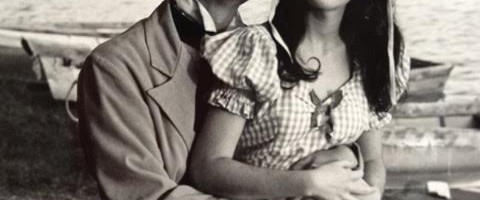

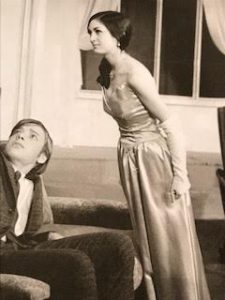

I had a good summer, portraying the glamorous actress, Irene Livingston in Moss Hart’s Light Up the Sky, a role originated by his wife, Kitty Carlisle, a fact I got to tell her years later.  I was also Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. We performed The Sorcerer in Operetta and, though always in the chorus, I was given a small part in the opening pantomime during the overture. In the Featured photo, I and my partner, David Maier, are in costume just before the start of the show. For the third time, I won the Chorus Award for Best Chorus Member; a record, I believe.

I was also Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. We performed The Sorcerer in Operetta and, though always in the chorus, I was given a small part in the opening pantomime during the overture. In the Featured photo, I and my partner, David Maier, are in costume just before the start of the show. For the third time, I won the Chorus Award for Best Chorus Member; a record, I believe.

There was one moon-drenched night that I will never forget. It was July 20, and anyone alive will always remember where she was when man first walked on the moon.

Camp was quite regimented. We wore uniforms, awoke to Reveille and went to bed by Taps. But this night, High School Girls were allowed to stay up late. A small black and white TV was brought in to the Sun Decker, a three story structure, long-gone, but at the time, a concrete haven for fun. It had indoor space for boat storage, ping pong, fireplaces for cook-outs on rainy nights, and decks outside to sunbathe on, recessed into the side of the hill sloping down to the lake and we, the last of the naïve generation who didn’t know the dangers of skin cancer, would douse ourselves in baby oil and lie out to soak up the rays when we could. It was inside, on the second level where we camped out on this particular night, packed in like sardines as we watched the scratchy image on the old TV.

My heart raced as the door of the space capsule opened and Neil Armstrong stepped out. I climbed over the bodies of the other girls and walked out to the edge of the railing around the concrete deck. I turned my back to the TV and looked out at the moon, reflected perfectly in the quiet lake below, gorgeous twin images of reflected light. Behind me, as in a dream, I heard Neil Armstrong’s voice: “One small step for man, one giant leap for Mankind,”

He spoke to me from that glowing disk I gazed at in the sky. How marvelous! How unthinkable. In an era of drug-induced hallucinations, my real experience far surpassed anything that could have been imagined. One of my countrymen really had landed on the moon; I had just witnessed it with my own eyes. And there stood 16 year old Betsy, looking out at Wabakanetta, this beautiful lake I had so enjoyed in my many years at camp. There was the reflection of the moon. But on this particular night, an American stood on the very real surface of that moon, which itself can only reflect light; twin reflections, far away, yet only as far as a pebble’s throw.