Nineteen sixty three unfolded into a year of beginnings. After years of post-adolescent frustration, I had sex for the first time. Having grown up in New England in the 1950s, nobody had told me or anyone else about the mysteries and techniques of copulation. There was no Joy of Sex, literally or figuratively. My parents could talk politics, science, and history, gossip about our small town’s antics, they could joke about sex but were not inclined to talk to their kids about it. Hence, I “entered” my maiden voyage on the storm-tossed seas of sexual intercourse with an athletic young woman who knew much more about having a good time in bed than I did.

I finished my freshman year of college that year. By the beginning of 1963, we had survived the end of the world as defined by the media as the Cuban missile crisis. At fair Harvard, cliques had set, the freaks had circled the wagons, and the study rate dropped to 33 percent.

Beyond the sheltering walls of Harvard Yard, our nation was embarking on a surge in the struggle for civil rights. Strategists in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference planned 1963 as a year for direct action — voter registration in Southern states, lunch counter sit-ins, marches to out Jim Crow to northerners. They organized a Birmingham, Alabama march for civil rights that was met with Birmingham Sheriff Bull Conner’s riot sticks, firehoses, and police dogs.

Hundreds were arrested, including Martin Luther King. His “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” began as a response to indignant white clergymen, but King’s letter became a manifesto for nonviolent protest and the need to end racial injustice in the United States. King’s letter, the reports and photos of that demonstration resonated ‘round the world.

Despite bloody, chaotic, and cruel treatment, these early non-violent protests succeeded. King and the SCLC had planned to be arrested and jailed. The arrests forced racial injustice into the system through unimpeachable lawsuits focused on the unconstitutional violation of American citizens’ civil rights. In the courts, the SCLC reasoned, the evidence of Jim Crow would be exposed for the nation to see. From the court cases, civil rights strategists hoped to bring Jim Crow to the attention of Congress.

Despite bloody, chaotic, and cruel treatment, these early non-violent protests succeeded. King and the SCLC had planned to be arrested and jailed. The arrests forced racial injustice into the system through unimpeachable lawsuits focused on the unconstitutional violation of American citizens’ civil rights. In the courts, the SCLC reasoned, the evidence of Jim Crow would be exposed for the nation to see. From the court cases, civil rights strategists hoped to bring Jim Crow to the attention of Congress.

Sixties America had begun to heat up. Freshman silliness prevailed in my Harvard dormitories but we read the papers and watched Freedom Riders’ buses burn from afar. We still spent more time listening to the fractious comedy of Lenny Bruce and Mort Saul and reading Paul Krasner’s satirical broadside “The Realist.” But within the sanctuary of Harvard Yard, rising social inequity and bad hygiene bred insanity that soaked into our lives like microbes through a semipermeable membrane.

Dennis, one of my freshman college roommates, a gay, working-class Trotskyite from Cleveland, had taken to sniffing glue and reading Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men —over and over. Dennis had become paranoid. Who could blame him? Gay, working class, a commie in Harvard’s hallowed halls? I believe Harvard had admitted Dennis as a social experiment.

By April, Dennis had landed in the university infirmary. When we entered his room, he desperately shushed us up from his hospital bed. “Shusssssh,” he whispered. “They’re listening.” He frantically instructed us to return to our dormitory room and destroy all his papers. “What papers,” we asked. “All of them!” His whisper was more of a scream than anything else.

Dismayed, we returned to the dorm and boxed up the clutter of papers in his desk. There was nothing worth hiding, just lists, diagrams, glue-inspired dribbles and doodles. Certainly nothing academic. Absolutely un-seditious. I don’t think the guy had cracked a book.

Dennis disappeared, never to be seen again. I’ve looked for him over the years, thought he might have become the Unabomber, but the spelling of the last name was off, and the lead fizzled out. So much for my bright but crazy roommate. I finished freshman year and immediately departed for California.

My cousin and I had been swapping letters over the year. He began UC Berkeley just as I began Harvard, and we had been corresponding over the semesters. I had been to California as an impressionable child and found it to be a wonderland. My cousin’s letters had morphed from rational narrative in architect’s block print into sweeping psychedelic drawings. My return to Berkeley in the summer of ’63, although nine years after my initial visit, proved that California had turned into a brave new world.

I joined my cousin in his passion for landscape gardening, cavorting in small work boats on the San Francisco Bay, exploring whaling stations and moored WWII Liberty ships. We took overnight drives to the Sierras and hiked into Yosemite’s high country. There, we tried to kill ourselves by embarking on hair-raising technical climbs that afforded views of 2000-foot views — euphemistically called “exposure — that demonstrated where your body would land on the talus slopes below, viewed between your boot-shod legs.

I joined my cousin in his passion for landscape gardening, cavorting in small work boats on the San Francisco Bay, exploring whaling stations and moored WWII Liberty ships. We took overnight drives to the Sierras and hiked into Yosemite’s high country. There, we tried to kill ourselves by embarking on hair-raising technical climbs that afforded views of 2000-foot views — euphemistically called “exposure — that demonstrated where your body would land on the talus slopes below, viewed between your boot-shod legs.

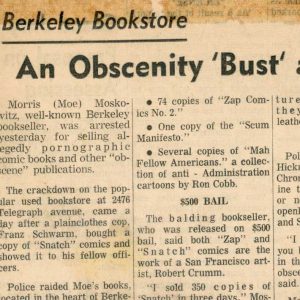

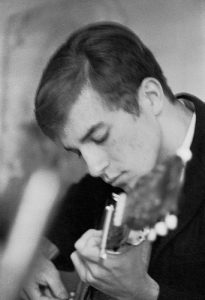

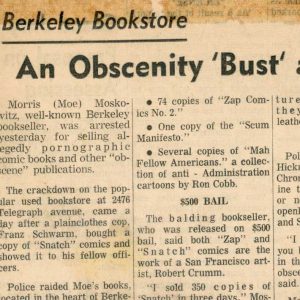

Berkeley, too, had burgeoned. There were beatniks and hipsters and anarchists and the beginnings of the Free Speech Movement. There were coffee houses and bookstores full of Ferlinghetti and Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg and — gasp — even a woman beat poet named Diane DiPrima. Folk music was everywhere, and my traditional folk music world had been turned upside down by Bob Dylan.

Berkeley, too, had burgeoned. There were beatniks and hipsters and anarchists and the beginnings of the Free Speech Movement. There were coffee houses and bookstores full of Ferlinghetti and Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg and — gasp — even a woman beat poet named Diane DiPrima. Folk music was everywhere, and my traditional folk music world had been turned upside down by Bob Dylan.

The Safeway grocery stores were open 24 hours a day, so the night people would come out to buy their oddities. Oh, and the women and girls were exotic, beautiful, and… largely unavailable. Like most late-blooming teenagers, I was hopeless at making moves. I did, however, find solace with the lovely daughter of a tugboat captain. I played the guitar under her window and— as Bob Dylan wrote two years later — she “invited me into her room.”

In late August, I said goodbye to my California family and began the long, hot haul back across the continent to Cambridge. I had not wanted to say goodbye to cousins and the California life that daily grew more adventurous in its love affair with nature, marijuana, and the mutual recognition of what we then called “freaks.” We proudly referred to ourselves as freaks, scruffy outsiders who were beginning to recognize one another as we stepped over the lines of societal propriety, to invent lives, “beyond the fringe.”

The cross-country drive froze into a highway duet — engine and tires — at 50 mph, no more, no less. Harriet had picked me up on a Berkeley billboard where notices for riders and rides fluttered in the breeze. She drove a Nash Rambler and was returning to Smith College. We had little to say to each other. Harriet gazed out the window, hot wind blowing her hair. She had little to say to her scruffy travellng companion. I was moody and silent, too. I liked the tugboat captain’s daughter. Most important, I didn’t want to go back to Cambridge.

In the Midwest, busses began to pass Harriet’s Rambler. Each bus sported a large banner saying things like “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” or “Civil Rights Now — No More Waiting!” Bus after bus roared past us. We could hear people singing over the roar of the buses, the highway noise, and our own tiny engine. Something was going on.

In the Midwest, busses began to pass Harriet’s Rambler. Each bus sported a large banner saying things like “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom,” or “Civil Rights Now — No More Waiting!” Bus after bus roared past us. We could hear people singing over the roar of the buses, the highway noise, and our own tiny engine. Something was going on.

By the time we hit Ohio, the Rambler’s AM reported a “largest ever” crowd gathering in the heart of Washington, D.C. It sounded exciting! The busses were headed for Washington and the Reflection Pool that lay between the Lincoln and Washington Monuments. “Hey,” I said to Harriet. “Let’s follow them. It’s not that far off our route.”

Harriet crossed her arms. She shook her head. Harriet was headed for Smith College, not Washington, D.C.

“But look!” I said. Another convoy of busses passed. “There’s something happening here…”

Harriet reminded me that I was driving her car. “We’re going to Amherst.” So…

I never made it to the March on Washington. Such are the turns of fate that shape our lives.

Cambridge seemed dirty, droopy, tired of its long, humid summer. The narrow streets felt constricting after my California summer full of sunshine, suntans, alpine challenges, and Berkeley weirdness. The “authorities” had turned down my request to join several pals in Adams House. Instead, they had shunted me off to the cinderblock-dreary confines of Quincy House. I never considered appealing the decision. The housing office had spoken. I felt better, however, standing in the Quincy House yard. I rejoined my embryonic hipsters, traded matchboxes of weed, and listened to the Isley Brothers sing “Twist and Shout” over a hi-fi speakers jammed into the stingy Quincy House windows. However…

Cambridge seemed dirty, droopy, tired of its long, humid summer. The narrow streets felt constricting after my California summer full of sunshine, suntans, alpine challenges, and Berkeley weirdness. The “authorities” had turned down my request to join several pals in Adams House. Instead, they had shunted me off to the cinderblock-dreary confines of Quincy House. I never considered appealing the decision. The housing office had spoken. I felt better, however, standing in the Quincy House yard. I rejoined my embryonic hipsters, traded matchboxes of weed, and listened to the Isley Brothers sing “Twist and Shout” over a hi-fi speakers jammed into the stingy Quincy House windows. However…

The performers weren’t the Isley Brothers; they were the Beatles. After playing folk music and listening to the blues for an impressive four years, I thought I had an ear to distinguish between white covers (bad) of black tunes (good). But the Beatles had me fooled. I’d never heard the band before, and they rocked “Twist and Shout.” I was impressed. As with so much of 1963, we had no idea what was about to happen — with the Beatles, the civil rights movement, the Presidency. Vietnam was still a mystery: Where was Saigon, and why were Buddhist monks burning themselves in public squares?

In their wisdom, the authorities had chosen to team me up with two preppy football players from Connecticut. The mismatch was so sharp that I couldn’t help but feel that I was being sabotaged. We had nothing in common and, when together, the two blond bruisers were insufferable. I grabbed the single bedroom, closed the door and listened to Dylan records while I studied and daydreamed, staring out of the slit windows that symbolized the claustrophobia I felt.

In their wisdom, the authorities had chosen to team me up with two preppy football players from Connecticut. The mismatch was so sharp that I couldn’t help but feel that I was being sabotaged. We had nothing in common and, when together, the two blond bruisers were insufferable. I grabbed the single bedroom, closed the door and listened to Dylan records while I studied and daydreamed, staring out of the slit windows that symbolized the claustrophobia I felt.

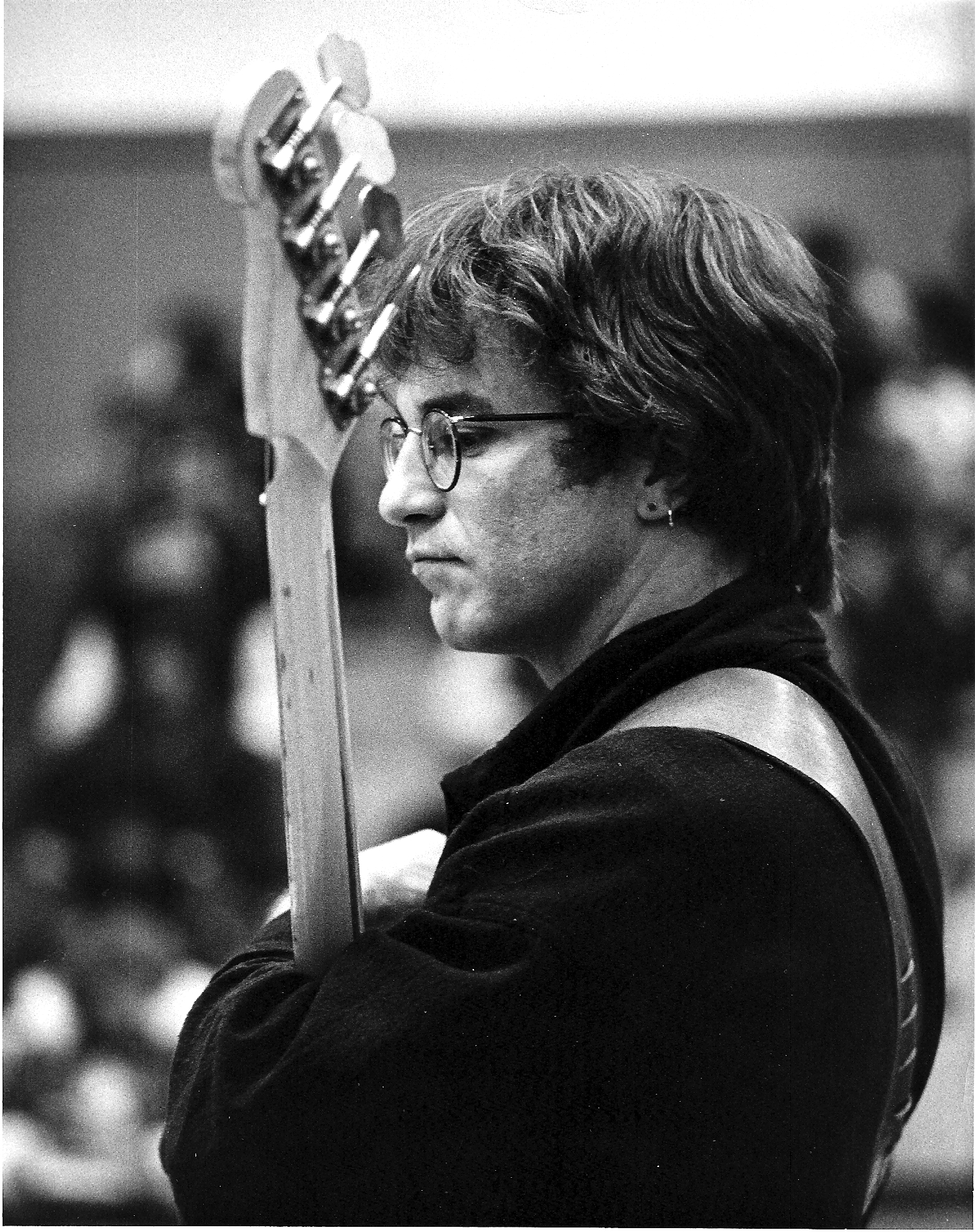

Football season came. The files of happy Harvardians with their Cliffie companions trooped beneath my windows to the stadium every Saturday while I remained dateless. I did, however, manage to escape the nasty hilarity of my jock roommates to hang out with a covey of folk musicians on the floor above me.

Contrary to popular claims, I don’t remember where I was when Kennedy was shot. I suspect I was in the dorm. I do recall watching the aftermath, the waiting, the final death verdict, Cronkite’s speculations on the black-and-white television. I remember being alone. I don’t remember speaking to anyone, just watching, suspended in the numbness that had enshrouded me during the October days of the Cuban missile crisis. I recall wandering up to the Square, to the newsstand at the subway entrance. Someone snapped a photo of me that showed up in the 1964 Harvard Yearbook. I must have been looking appropriately sad.

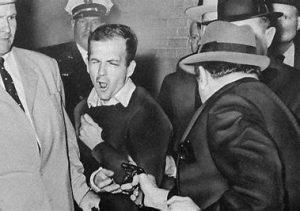

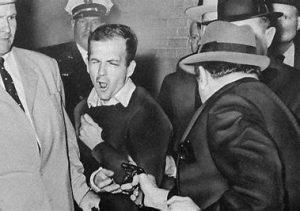

Two days later, I stood stock still in the wretched lobby of my Quincy House dorm and watched — in real time — as some fat guy in a fedora pushed through the crowd in the basement of the Dallas courthouse and shot Lee Harvey Oswald in the gut. I thought Oswald was a patsy even then; I knew that somewhere, there were bigger fish to fry.

Two days later, I stood stock still in the wretched lobby of my Quincy House dorm and watched — in real time — as some fat guy in a fedora pushed through the crowd in the basement of the Dallas courthouse and shot Lee Harvey Oswald in the gut. I thought Oswald was a patsy even then; I knew that somewhere, there were bigger fish to fry.

I do remember a familiar lack of emotion over JFK’s assassination. As with the nuclear nightmare of the U.S. – Soviet arms race and mushroom clouds, or the big showdown off Cuba, the loss of the “Age of Innocence” left me cold. What innocence? What Camelot? I wasn’t a big Kennedy fan. I didn’t think his often-repeated slogans “Ask not what you…” meant much. I didn’t like his attack on Cuba, I thought Bobby Kennedy’s integration plans were disingenuous, and I saw the Peace Corps as a Marshall Plan for kids who would become well-intended advocates for American imperialism. I was old for my age.

I had lost my “age of innocence” when Eisenhower murdered the Rosenbergs. The two communists were people just like my parents. They had joined the communist party during 1930s, when they were in their 20s and socialism seemed possible. As a child I wondered when the FBI — who periodically came to our door — would take my parents away and fry them, the way they had done to the Rosenbergs. My father was blacklisted in 1947 and could never find enough steady work to feed his family before he died in 1964. So, for me, the violence of 1963 seemed linked to the violence of 1953, when McCarthy was at his pinnacle.

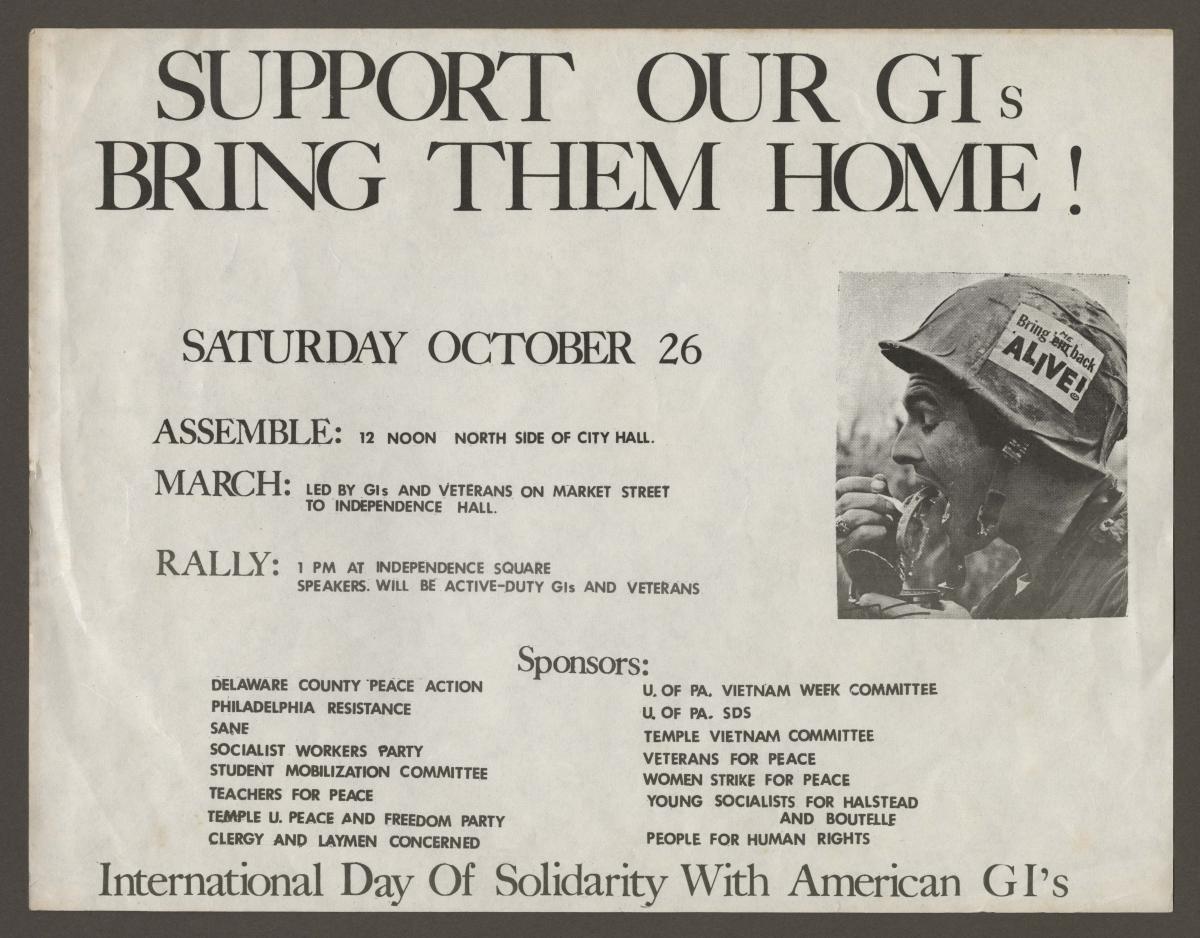

Thanksgiving came and went, the nation mourned, Johnson took over, Vietnam began to rumble and then — as we had done in Iran (1947), Guatemala (1954), had tried and failed in Cuba (1961) — the CIA set out to block an election and facilitate a regime change in Vietnam. We succeeded in halting the election that would have unified Vietnam in 1963. One hundred American advisors died in Vietnam that year. We all know what happened after that.

At the semester break, I walked out on the two football players. I had secured a bunk with my folk singing pals in Quincy House and looked forward to taking a year off to work with a new student activist group called SDS —Students for a Democratic Society. Beginnings had begun.

# # #