My Love Affair with James Joyce

Playwright Israel Horovitz was caught by several women who said “Me too.”, and so was Prairie Home Companion creator Garrison Keillor; filmmaker Woody Allen’s private life has been far from exemplary; abstractionist Pablo Picasso and novelist Philip Roth were notorious womanizers; the 17th century painter Caravaggio killed a man in a brawl; poet Robert Frost was a domestic abuser; and composer Richard Wagner was a vehement anti-Semite. Yet despite their reprehensible behavior, it seems I’m able to separate these artists from their art – perhaps because I love their work and want to enjoy it.

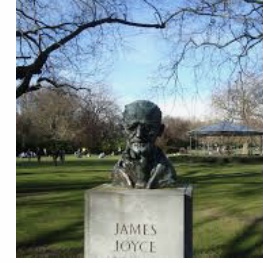

On the other hand, as far as I know, there was nothing reprehensible about author James Joyce. But to me his life – his Irish Catholic upbringing and his eventual disillusion with the faith; his unlikely romance; his self-exile from his homeland; his painful and lingering eye problems and innumerable surgeries; his battle against the censorship of his work – is all so intriguing while his literary gifts so monumental I can’t forget his own story while reading the stories he’s written.

And truthfully I’m a bit obsessive about James Joyce. I’ve read his all books; seen the stage and screen adaptions made from some; read biographies of Joyce and his wife and muse Nora Barnacle; am fascinated by his innovative stream-of-consciousness style, and his encyclopedic knowledge of languages, history and cultures; and am familiar with the facts surrounding the banning of his books and the sensational obscenity trial over the publication of his novel Ulysses in the 1920s. And twice my literary love affair with this Irish writer took me across an ocean.

Boulder, CO / New York, NY

It started innocently enough one summer in the late 1960s when I was living in Denver. I decided to take a course, discovered that the University of Colorado at Boulder had some great non-matric offerings, and signed up for one entitled Three Great Novels. I honestly don’t remember the other two novels I read in that class, but the third, James Joyce’s masterpiece Ulysses, was unforgettable. In fact it changed my life, at least my reading life, as I now measure every work of fiction I read against that great book – and disappointingly most pale in comparison.

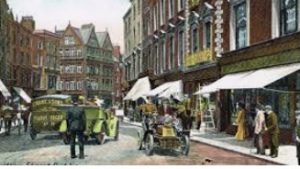

That summer I’d drive the 30 miles from Denver to Boulder and, through Joyce’s astonishing genius, be transported from a sunny, Rocky Mountain classroom to the city of Dublin at the turn of the 20th century.

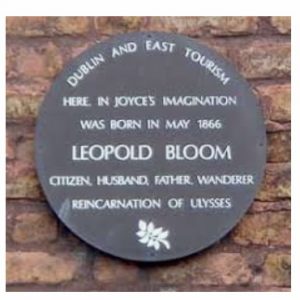

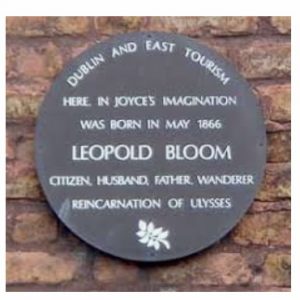

After that I couldn’t get enough, and back home in New York I took more Joyce courses over the years – at Hunter College on a study sabbatical; at NYU’s adult ed program; at the 92nd St Y; and at my neighborhood Barnes & Noble I joined a Ulysses reading group that met for 18 weeks, each week covering one of the book’s 18 famous “episodes”. And every year at Symphony Space I celebrated Bloomsday on June 16th, the date on which Ulysses’ fictional Dubliner Leopold Bloom wanders the city and his wife Molly famously betrays him.

And then I heard about Dublin’s James Joyce Summer School.

“I’m going to Ireland.”, I announced to my family.

“Promise me you won’t eat meat.” my husband said. It was the year of the Mad Cow.

I promised.

Dublin, Ireland

I’d been to Dublin well before my first James Joyce Summer School summer, and since I was already a Joyce lover back then, I’d taken the celebrated walking tour of the city sites associated with his books.

Our guide had led us from 7 Eccles Street where Ulysses’ protagonist Bloom supposedly lived with his wife Molly whose celebrated “Yes” ends the book; to Sweney the chemist; to Davy Byrne’s pub; to the Ormand Hotel; to the National Museum; and to Dublin’s red-light district that Joyce calls Nighttown.

And I also went to the Martello Tower where Joyce set the first episode of Ulysses. There the aspiring young writer Stephen Dedalus – obviously based on the author himself – lives with “Stately, plump” Buck Mulligan who famously shaves as the book opens.

That tower is one of many “Martellos” built as defensive forts by the British in the 19th century to dot the Irish coast. And there, like legions of Joyceans before me I’m sure, I rambled down the beach intoning Stephen’s thoughts, “Am I walking into eternity along Sandymount Strand?”

Of course arriving back in Dublin for that summer school program was exciting. The school was run by University College, Joyce’s alma mater, and we met in the same building where the author attended class a century before. Thus I walked up and down the very staircase Joyce did, and looked out at the city through the same windows as he did with his legendary poor, myopic vision.

But my initial delight on arriving was clouded by a serious decision I had to make. Classes were offered in all of Joyce’s famous works and I had signed up for Ulysses. But the enrollment for that course was too large, and so it was decided to divide us into two sections – a beginner and an advanced – with Fritz Senn, a world famous Joycean, teaching the latter. Each of us was to decide by next morning in which class we belonged.

I called home with my dilemma. I explained that I’d met my several dozen fellow students at a welcoming session and knew some would be reading Ulysses for the first time, obvious candidates for the beginner class. But others were obviously well-versed in Joyce including a professor of Irish lit at a top American university, and a scholar from Sofia who had translated Ulysses into Bulgarian! I asked my family what I should do.

“You love that book, in fact you obsess over it.” said my son, “If anyone belongs in the advanced class it’s you. Go for it Mom!”

And so I did, and in fact I got to know the renown Joycean who taught the course quite well as we lived in the same dorm. Actually our dorm, Muckross House, was a convent for novice Dominican nuns throughout the year, but apparently the nuns had a summer break, and then their very spartan rooms were rented out to us Joyce-lovers.

But there was nothing spartan about our delightful breakfasts in the convent dining room with bowls of fresh fruit, and eggs, and cold meats, and hot porridge, and heaps of buttered toast and strong Irish tea.

And walking to class every day was also a delight, even on a drizzly Dublin morning, as we crossed a little footbridge over the Grand Canal that flowed south from the River Liffey, and then cut through St Stephen’s Green, the loveliest and greenest city park imaginable.

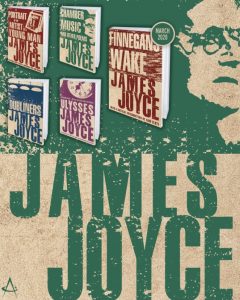

We actually studied not one but two of Joyce’s works during each summer session, and because I returned for a second summer a few years later, in addition to Ulysses I read his famous short story collection Dubliners, his brilliant autobiographical novel Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and his nearly impossible-to-read, experimental novel Finnegan’s Wake.

My appreciation of Joyce during those summer programs surely grew, and so did my appreciation of Guinness on draft – much creamier than the Guinness we drink in the States. And I learned it’s customary in Ireland for professors to adjourn to a nearby pub after class and for their students to follow. Every afternoon we did just that, and at a large table in the back reserved for us, we’d spend the next few hours drinking and talking about literature and life. My friend Jeanne joined me the second summer, and although we had lots of reading to do for class each night, we nevertheless found time for some serious pub-crawling as well.

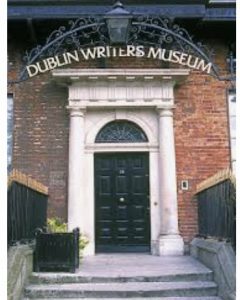

Then one day I decided that after class I’d go to the Dublin Writers Museum to learn more about Joyce and Ireland’s other great literary icons – Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift, William Butler Yeats, Sean O’Casey, and George Bernard Shaw.

I called the museum for their hours, and when I heard they close at 5:00, I worried that I might not make it in time.

“Don’t fret Luv,”. said the Irish voice on the phone, “we’ll keep open until you get here.”

Erin go bragh!

– Dana Susan Lehrman