We are five months into the pandemic. Massachusetts was one of the hardest-hit states and took a long time to reopen. That’s fine with us. Dan ends conversations saying,”Stay healthy, stay safe, stay sane”. In a normal summer, we would have moved to Martha’s Vineyard for the season the week before Memorial Day, but nothing about this season is normal. Dan was on the Vineyard for about 10 days, setting up, supervising painting and other work, then came home (I had doctor appointments, delayed from March and April), so for the first time in 24 years, we did NOT spend Memorial Day on the Vineyard. Dan’s birthday is May 25, which is usually that weekend. We had a quiet weekend in Newton. He had already received his gift, but I got him a good chocolate cake. My last appointment was June 16 (our 46th wedding anniversary, also always celebrated on the Vineyard, but not this year), and we moved down the next day.

This year, every large gathering, fundraiser, parade, fireworks, EVERYTHING has been canceled. Restaurants opened for outdoor dining in mid-June and indoor dining in late June. We are only OK with outdoor dining. Barricades have been set up along Main Street and elsewhere to accommodate more tables for outdoor dining. Everything is socially distanced.

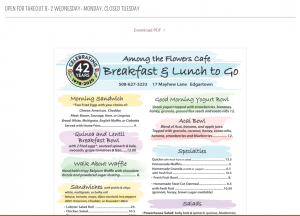

We are doing a lot of take-out, from a few select restaurants. Our favorite café, where we even have the owners’ cell phone numbers, won’t be open for dinner at all this summer. They are too small to make it worth their while. They are only doing take-out breakfast and lunch. We bring in food before they close and eat it for dinner. I can still get my favorite “summer” salad, eat healthy and support them. They are working harder than ever; finding it difficult to get help, while up-ending their business model.

My workout routine was still my Zoom classes online when I first moved down. Just a different view. The house computer is in the kitchen, behind the table…I can’t move that aside, as I do the ottoman in my den in Newton, so I use my iPad in my bedroom. But the workout is just as good. Now our club is open. Classes are under a tent on the great lawn, a bit of a slope, but usually a pleasant breeze (not so pleasant with heat and humidity) and nice views of flower beds (and the thwack, thwack from the nearby tennis courts). the in-door gym reopened on July 6. Everything is reconfigured for social distancing and keeping us safe. Some machines (including my beloved recumbent bike) has been moved to the studio, since all classes are outdoors. There are shower curtains hung between each machine. Masks must be worn at all times, sanitize hands upon entering and leaving, wipe down machines before and after each use. Machines that could not be moved are roped off, and will be changed after a few days, so they can be rotated for use. There are no mats, hand weights, bosa balls, stretching place. You come in, use your machine, leave. There are head counts to ensure low numbers of people at any given time. Lockers are taped off, not to be used. I feel perfectly safe just using the bike and leaving. I was given a small towel upon entering (we always had to sign in) and a small pack of sanitizing wipes of our own. Outdoor classes will be canceled in inclement weather. I will continue to do a mix of live and Zoom classes, but it is nice to see people again. Yesterday we learned a club member who participates in the tennis program tested positive for COVID-19, so the whole family is being tested and will quarantine. No one had used the Fitness Center. But still, this has come very close to me now.

We are die-hard mask-wearers, but are very concerned when we see too many people wandering around not wearing masks. Dan takes long walks as part of his exercise regime and says about 90% of the people he sees are NOT wearing masks! Perhaps because they feel they are outside and can be far enough away, but it makes him crazy. Most carry one, but don’t put it on, even as they pass him. He goes out of his way to avoid them, then asks, brusquely why they aren’t wearing a mask. This country has gone crazy. We have seen an influx of people since we came on June 17. Tourist season is upon us. We are afraid to go to the beach. We don’t want to see large crowds. We are happy in our own backyard with our swimming pool. As of July 10, Edgartown mandated that everyone in downtown (where we live) MUST wear a mask or pay an increasingly large fine.Since then, mask compliance has improved. We read in the local paper that COVID cases are increasing (slightly, two a day, hardly a spike, but still worrisome) as the tourists arrive. This is a small island with a 25 bed hospital and few of them are ICU beds. Real emergencies are flown off-island to Mass General, but we don’t want to be overwhelmed.

In a normal year, in late June, we would go to the other island to attend the Nantucket Film Festival. We already bought our patrons passes months ago. We thoroughly enjoy it and always attend with close friends, usually run into friends who have homes over there, and see great films ahead of their release, accompanied by a Q&A with the director or producer, or sometimes even the leading actor. The producers of the festival do an excellent job and it has grown over its 25 years in existence. In April, we got a call from the Executive Director telling us they had to cancel; we could get our money back or roll it forward to next year, which we chose to do (hopeful there will be a vaccine by then). Then we find in our email in June, they are doing an online streaming “NFF Now: at Home” over the course of a week. We signed up, got the service and watched several good documentaries, each followed by a Q&A with the director, as well as a short subject series. They did a fine job and we thought it was well-worth the money.

Friends from out of state who have to get on a plane probably won’t come to the island at all, as cases around the country spike. It is strange and sad not to see them. I heard a Zoom lecture today and one couple was also on, stuck in Florida. We texted greetings to one another. I was on a Zoom camp reunion one Sunday night recently. I briefly saw my brother and several other Retrospect writers, but SO many people showed up that there was no way to manage it, and I couldn’t speak with the friends I really wanted to, so we have organized our own group’s reunion. Even that will be about 15 people, which could be difficult to manage, but at least we can try to say hello.

The only people we socialize with are close friends, in our backyard, theirs., or perhaps a beach picnic, after hours. We bring our own food, sit at different tables, but at least we can visit. Trying to make this a pleasant experience, we ordered new furniture; a larger table that can seat six, but, if sitting at opposite ends, we could probably seat two couples and still be far enough apart. It has a fire pit in the center, so as the days grow shorter, we can still be warm and comfortable with friends. We had to tear up our patio to run a gas line to the center. Lots more work in the backyard. The new furniture arrives today.

We don’t know when we will be able to see our children, in London and St. Jose, CA, again, as the UK won’t let us in and we don’t feel safe getting on an airplane anyway. We don’t know when we will feel safe again. David has set up a few “Google Chats” for us. It is difficult, across eight time zones, to find a time that works for all of us, but at least we can all see one another and chat. The sound quality isn’t great, but we can be together and check in. Evidently Zoom doesn’t work well for David.

We are all trying to stay safe and healthy. We are not comfortable eating inside or going to a movie theater, no matter how many seats are roped off. This virus is spread by droplets in the air. We don’t want to tempt fate.

I heard an epidemiologist speak this week (of course via Zoom, like everything else in the world right now). He suspects COVID-19 may be endemic. It is not going away and the vaccine, whenever it surfaces, may will not be a panacea, but rather, as with the flu, it may mitigate the severity of the disease. We may just have to learn to live with this, continue to mask, wash, distance, even with a viable vaccine (and he readily admitted that many people will not try it at first, but wait to see how it impacts the early adopters – so there’s that too). Lots of questions, few answers, as scientists continue to research and expand their knowledge of the virus. The “new normal” is evolving, even as we learn more about this horrible disease, which he said absolutely crossed from a bat to a human. They definitively know that now that they’ve have the genome for COVID-19, just published last week.

This is, indeed, the summer of the backyard. Hoping everyone reading this stays safe as well.