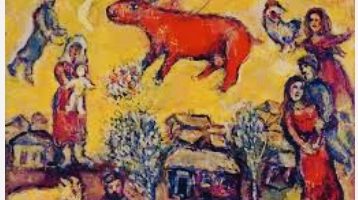

Chagall’s Cows

When our son was a toddler many friends began fleeing Manhattan. They couldn’t imagine raising a child amid all the dirt and crime.

“But think of the culture!”, I’d say.

Noah at 5, wide-eyed at the Met’s Arm & Armor exhibit. And making Purim masks at the Jewish Museum, and model dinosaurs at the Natural History. And reading the night sky at the Planetarium, and delighting when Red Grooms took over the Whitney.

But my sweetest memory of Noah’s museum-going childhood was at a Chagall exhibit at the Guggenheim when he looked up from his stroller to ask incredulously, “Another cow who’s flying?”

RetroFlash / 100 Words

– Dana Susan Lehrman