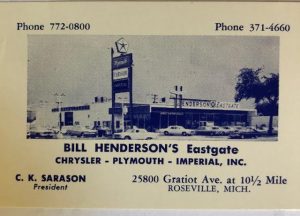

I grew up in Detroit, Michigan; Motown, USA, in a family deeply involved in the automotive industry. My dad, with a partner, owned a Chrysler dealership and there was always a new car in the driveway (he’s the one just to the right of the car door holding his pith helmet with his arm out in the Featured photo dating from 1966; a full-page ad in our local paper when the new cars came in. The Detroit Auto Show was REALLY something). He usually drove an Imperial. It was huge! One even had a record player inside. I remember lying down on the plush carpet in the back.

Dad worked hard; six days and two nights a week. Mom had one of the first Valiants off the production line, a silver beauty. She had a maid five days a week who did all the cleaning, laundry and most of the cooking. We lived in a three bedroom house. Thinking back, I’ve wondered how there could be so much to clean on a daily basis.

Detroit is divided by mile markers, starting at the Detroit River, heading north. The city limit is 8 Mile Road (as in the Eminen song). We lived a block away on the north end of town. We also lived a block from the huge Woodlawn Cemetery, now the final resting place of the great Aretha Franklin, as well as Rosa Parks. This has become a famous cemetery, but when I grew up, it felt vaguely creepy to me. On Halloween it was just plain frightening. The night before Halloween is called “Devil’s Night” in Detroit. Supposedly, the dead spirits came out of their graves to haunt all of us, and there were obviously an abundance of them in close proximity to me. It was a time of mischief in Detroit. Kids came out to egg or TP houses, or worse. I was not a mischief-maker, but Detroit was notorious for this.

In front of my elementary school. I am in the second row, toward the left, short dark hair, bangs pushed back.

I attended the Louis Pasteur Elementary School at 19811 Stoepel Street, which was K-8, a huge place, racially diverse at the time (more so as the years passed). It was a good school, though over-crowded. The above photo was probably the first and second grades. I think I was in second grade at the time. I was surprised when I looked up the address, as my parents’ first house was on Stoepel. It was taken by the city by eminent domain (my parents were compensated) to build a public parking lot. The school, and my classrooms, were large; typically 30-32 kids to a room. Because of over-crowding issues, if you were born between December 1 and February 28, you started school at the semester break, in February, which I did (my birthday is December 10), so I was always half way through with a grade in June. Before entering high school, which did not have that weird off-set, kids went to summer school to make up the half grade and enter high school (no middle schools in my area of Detroit), ready for 9th grade. We moved to a near suburb, adjacent to the Detroit Zoo, when I was half way through 5th grade. I was tutored for four weeks in math and just skipped ahead to 6th grade; now the youngest in my class; not socially or physically mature.

After their first house was taken, my parents moved to 20209 Briarcliff Rd, which is the only house I ever knew in Detroit. It seemed like a great place to live. Briarcliff was just three blocks long, full of playmates for my brother and me. My best friend lived next door with two older sisters. A boy about my brother’s age, with an older sister, lived on the other side. I’m still in touch with the older sister.

The Good Humor truck drove up the street, clanging its bell in the summer and we’d all run out to get our treats. We played games like the “kick the can” or “hide and seek” until the street lights came on. Then we knew it was time to head home. I learned to ride a bike, going around the block from Briarcliff to Renfrew. My friends Joanie, Patty and Julie lived there and I could visit them. The brilliant journalist and political commentator, Michael Kinsley also lived around the corner on Renfrew. He was a few years older, but his sister Susan was my age and in my grade at school.

We called “soda”, “pop”, most notably, Faygo Red Pop, a local brand. The best was Vernor’s Ginger Ale, also brewed locally. Sander’s made the best fudge sauce and cupcakes. We would sit at the counter for ice cream sundaes.

Our house was small but seemed ideal to me. My parents had an en suite master bedroom at the top of the stairs. Rick and I had our own bedrooms around the corner from each other. We shared a bathroom with a tub (my parents just had a shower) near the stairs landing. No air conditioning, my father would put out a big floor fan opposite my brother’s room on hot summer nights to ventilate the rooms. One of my windows overlooked the driveway. I’d listen for my father’s car to pull in at night. Then I could rest comfortably, knowing that he was home.

When my brother’s tonsils were removed and he was bed-ridden for a week, my parents got their first “portable” TV, a huge thing on a cart that could be wheeled around upstairs. With my brother in bed, I’d join him watching American Bandstand in the late afternoon. I loved Frankie Avalon songs and sang “Venus” to the stars after the lights went off (“Venus, goddess of love that you are, surely the things that I ask, can’t be too great a task’). I was a dreamy, romantic child. The house TV was in the paneled den, where Rick and I watched The Mickey Mouse Club earlier in our lives (I loved Bobby Burgess). I did that instead of practicing the piano. I was hopeless. Sunday night, the family gathered there, three of us on the couch, my dad in his easy chair, and watched Ed Sullivan and other family entertainment. The house had a formal living room, but that was for birthday parties and piano practice.

A small kitchen, breakfast room and dining room completed the downstairs. Off the dining room was a great screened-in porch where we spent hot summer nights. Dad listened to baseball games on his transistor radio. We could smell the flowers from the garden (as described in The Flowers That Bloom in the Spring (Tra la)). The basement had a finished room where Rick’s Cub Scout troop met. We carved the Halloween pumpkin in the scrub sink next to the washer/dryer. And there was a storage room under the steps where we huddled for safety against the fierce Midwest storms.

It seemed like an ideal upbringing. Until the millage failed. The millage was the part of the property tax that paid for the school system. I was only 10 so didn’t understand it all entirely, but knew there was a ballot initiative to vote for higher taxes to fund the school system. My girl friends and I made signs and wandered through the neighborhood, campaigning in favor of the initiative, but it was voted down. My parents knew this meant the school system, already over-crowded, would go downhill rapidly. I was already enrolled in Liggett, a good private girls’s school (Gilda Radnor’s alma mater), but instead, they quickly found land in Huntington Woods, and a cousin built us a new house. It wasn’t quite complete in September, 1963 when the new school year started, so I commuted for a few weeks. It was larger than our current house, a center-entrance Colonial with 4 bedrooms, still 2 1/2 baths, but deep walk-in closets and central air conditioning. Of course it was new and modern, but I was happy where we were.

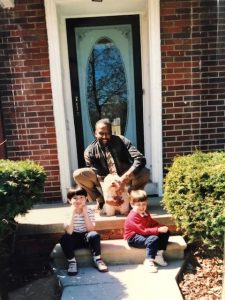

We sold Briarcliff Rd and moved to Huntington Woods on October 1, 1963. It seemed to mark an end to a happy period in my life. I returned to the old house once, with my own children, as described in Family Defined by Place. I found the neighborhood still quite nice, full of happy memories. The gentleman who owned my old house was kind enough to let us in and show us around. The house had changed little and I was happy to share it with my own small children, who were 8 and 4 years old at the time. The owner’s name, like my brother’s, was Richard. The house had come full circle. After the turbulent years in Huntington Woods, it brought me peace to see it again.