Close calls can be close only because of a chance occurrence, thought, or action. Like the so-called “Butterfly Effect” they often yield their own legacy, and in my father’s case, raise questions in my mind as to luck, responsibility, and personal values.

When I was a young teen, my father related, as best I recall, the following:

It was on St. Patrick’s Day 1953, in the middle of the Cold War, when a squadron of eight RB-36H’s left the runway in the Azores Islands, heading home to South Dakota for what promised to be a grueling 20+ hour flight strapped into uncomfortable seats in nasty weather. A circular storm system rotating clockwise promised a 100-knot headwind that would delay the return even more. The RB-36H was a specially modified B-36, a six propeller, four jet behemoth dreamed up by General “Bombs Away” Curtis Lemay, designed to penetrate Soviet Airspace to take photographs in “peacetime” and to drop a single nuclear bomb should war break out. Each plane had a crew of 23 servicemen.

This was more than a training mission, as the squadron was also testing whether they could sneak into the United States on the return trip without being picked up by US radar, intercepted radio communications, or visual observation. The plan was to fly close to the surface of the Atlantic and gain altitude only after entering US airspace. The crews were told not to use their radar, and to make no in-flight radio transmissions. Entry into North America was over Newfoundland, Canada.

Sitting in the co-pilot’s seat of the lead airplane was Brigadier General Richard Ellsworth, the officer in command of Rapid City Air Force Base in South Dakota. As the base commander, he didn’t have sufficient recent hours and training to be in command of the plane. He was basically along for the ride.

My father, then a First Lieutenant, was a navigator in one of the other planes. It was his responsibility to know where the plane was, and to tell the pilot where to fly to get back home. The flight left in the early daylight hours in the Azores, and flew through the night over the Atlantic. It was difficult to see the water below, and, with the cloud cover, virtually impossible to see any stars above. Sometime before dawn, he and the pilot agreed to gain altitude, violating the ground rules of the mission, to take a peek at the stars above the clouds, thereby allowing my father, trained in celestial navigation and armed with an Omega watch, to determine where they were. I don’t know who made the suggestion, but the information it produced was startling – they were over a hundred miles closer to land than expected. It turned out that over the night, the storm had migrated north. Rather than facing a headwind at the northern edge of this circular storm, they were at the southern edge. No longer hindered by the wind, they were instead pushed along at a rate far faster than anticipated. Armed with this information, the pilot gained altitude when new calculations indicated he would be approaching the edge of North America.

It turns out that the decision to take a peek and violate orders was, according to my father, followed by each of the other crews on this mission. (Other accounts said that some crews were able to see the stars through a break in the clouds.) At any rate, it is clear that the crew of the Commanding General’s plane stuck to the orders. At about 4:40 a.m., in a blinding rainstorm, it ran into a 900 foot hill at an altitude of 800 feet twenty miles inland from the Atlantic coast in Newfoundland. Everyone aboard was killed in what witnesses described as a tremendous fireball. The Air Force sent up another plane, a B-50 (the successor to the B-29 that dropped the atomic bombs in 1945) to search for the RB-36. It, too, crashed for unknown reasons, and was never recovered.

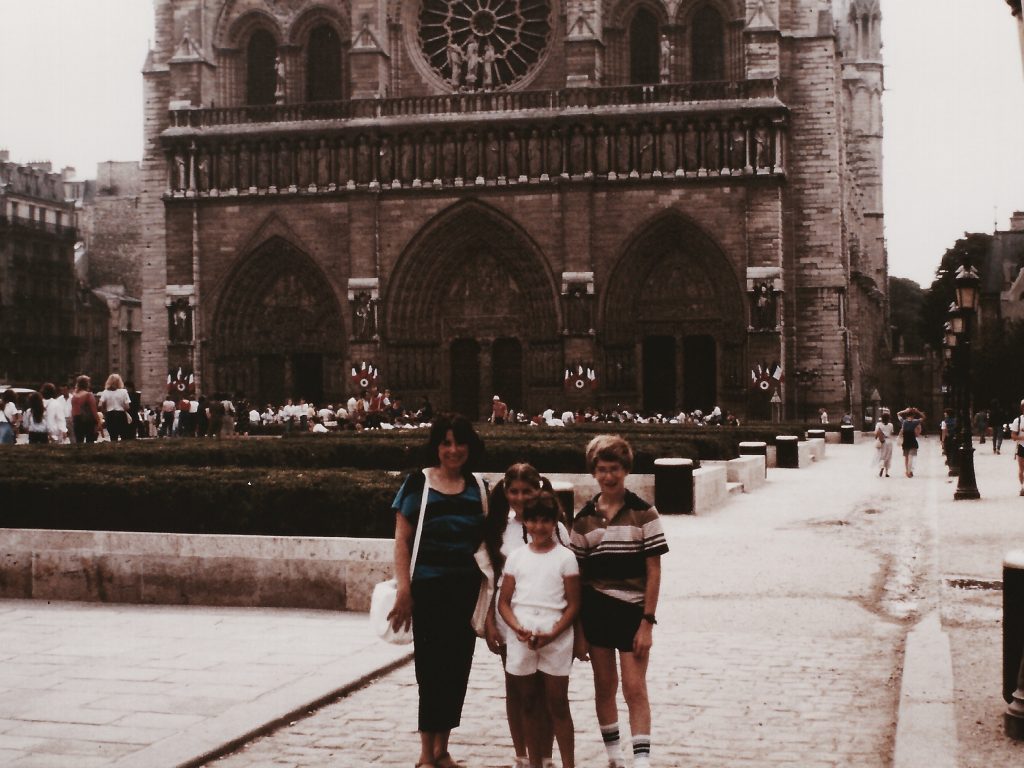

Families waiting for the crews got word of sketchy news reports of a crash involving an as-yet unidentified USAF plane. My mother, like other wives, called the Base. No information was forthcoming, and, no doubt, the person in the base command building had very little to give. Probably breaking protocol, and after pleading by my mother, he said that the Lieutenant had checked in. Our family did not escape unharmed, however. My grandmother, who also heard radio reports, was certain that my father had perished, and suffered a non-fatal heart attack which left her out of breath for the rest of her life. She had survived being struck by lightning and being bitten by a rattlesnake, so it would take more than a heart attack to take her down.

Soon thereafter, in a ceremony attended by President Eisenhower, Rapid City Air Force Base was rededicated as Ellsworth Air Force Base.

What strikes me, 67 years later, is the lesson my father imparted to me after telling this story – don’t obey a stupid order. It may end up killing you. To my father, at least, this mission was a close call. To others, of course, it wasn’t.

But other questions remain. Did my father accurately state the facts? And do I remember accurately what he told me? And more haunting is a question raised years later by my twin brother (the good twin), and a question that never occurred to me (the evil twin) – did my father, or any of the other crews, who discovered their location only by violating orders, have any responsibility to break radio silence to alert other crews who might not have made the same navigational discovery?