“Behold it is the Springtide of the year.

Over and past is Winter’s gloomy reign.

The happy time of singing birds is near,

And clad in bud and blooms are hill and plain.”

That is the first verse of my favorite Passover song. I sang it in Junior Choir at my Temple. I even sang a solo verse. I eagerly awaited the portion of the Seder when this song was sung. Passover is the only Jewish holiday which is entirely celebrated at home with a Seder which translates to “order”, as there is a specific order for the entire service, a few songs are sung throughout, but the general ones happen at the very end. Alas, this song, sung when I was young, no longer makes the cut. Call me and I’ll sing it for you.

As we know from the overblown movie epic “The Ten Commandments”, Passover celebrates the Exodus, when the Israelites, who had been slaves in the land of Egypt for generations, are finally allowed by the Pharaoh to flee, leaving most possessions behind, and escape, unharmed, across the Red Sea, only to wander for 40 years through the desert until they arrive in Judea, the Promised Land. Because Moses, their leader, lost his temper once, he is not allowed to enter. It is left up to Joshua to lead the 12 Tribes of Israel into the “Land of Milk and Honey”.

So we celebrate freedom each Spring with various special foods, rituals, songs and important questions. Because our people had to leave so quickly, they couldn’t wait for their bread to rise, so the bread they made was cracker-like. It is called matzah. There are other symbols on the Pesach plate too, each with a special meaning, some reminding us of the tears shed by our slave ancestors, some of the mortar for the bricks they used to build the monuments to the pharaohs. Some are symbols of Spring and renewal, some symbols of the ten plagues, increasingly destructive, brought down by God to prove He is mightier than the Egyptian gods and Pharaoh must let the Israelites go free.

During the Seder I attended (more on that later), we were reminded, as the Israelites crossed the sea safely, then saw the sea swallow their oppressors, they rejoiced. But the Almighty admonished them. The Lord reminded them that ALL people are children of the Lord. God takes no delight in anyone’s destruction and caused the Children of Israel to stop celebrating the death of their enemy. A powerful lesson for today.

The word “Pesach” means to pass over. It also refers to the Paschal lamb that was sacrificed for the last plague, the blood used to mark the doors of the Israelites’ homes, as the final plague was death of the first-born son. The Angel of Death “passed over” the homes that had the marking on the sides of the doors, but no one else was spared, including the son of the Pharaoh himself. He relented and let all the Israelites go free.

Thousands of years later, as Christianity was taking root, the lamb came to symbolize the sacrifice of Jesus and “lamb of God” has a place in the Christian liturgy. More sinister, that lamb’s blood on the door posts of the house took on a different meaning. Particularly during the Middle Ages, but at various other times as well, ignorance and superstition took hold, dark tales were told, beliefs circulated of the need for the blood of a Christian child for Jewish ritual; for the making of matzah, or for the four cups of wine, drunk on Passover. Ignorance, superstition, conspiracy theories, fear of “the other”; all come from ignorance, lack of tolerance, knowledge, belief in science, love and acceptance of fellow human beings (as is taught in most moral religious theory). This was true then as it is now. Ignorance, superstition and fear are powerful forces for evil.

The first incidence of this took place in Norwich, England as a crowd rose up, killing Jews. This is called “blood libel” and caused Christians to hate Jews, even to kill many at this time of year. It was only within the past few decades that the Pope formally denounced the notion of blood libel and officially “forgave” the Jews for the death of Jesus. Easter (also a spring festival with bunnies and chickens), harkens back to pagan springtime rites as well.

We probably all know that Jesus’ Last Supper was a Passover Seder. My father loved to tell jokes and was a gentle man. The following was one of his favorites and he told it every year as we gathered, waiting for the Seder to begin: “Just think, 2,000 years ago tonight Jesus said, “OK, everyone who wants to be in the picture, sit on this side of the table.”

Passover was always a fun time in my household. For many years, we celebrated at my Aunt Pauline’s house with many aunts, uncles and cousins spread out across two rooms of her small home. I’m not sure how she served so much food or how we got through the entire Haggadah, but we did, with children running everywhere. Mayhem, but such fun!

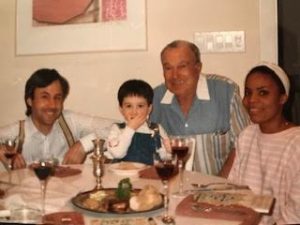

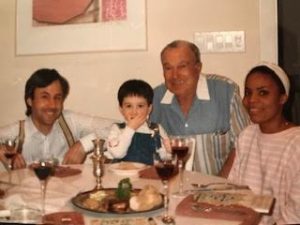

At a certain point, we moved over and celebrated one block from my house at my parents’ best friends, Ray and Mildred Berry. The following photos are from 1973, during my junior year at Brandeis (which would shut down for the holiday, as there are certain foods that are off-limits, so easier to shutter the cafeterias and send everyone home) and while my brother studied at Hebrew Union College for the rabbinate. I found these in one of my mother’s albums.

Mildred & her mother, at the foot of the table.

Don Berry, me, Rick

Grandma Hannah at the far end, Ray (barely visible) at the head of the table.

They had three children of their own, some close in age to us, Ray’s mother would often attend. She was a former opera singer and Ray played piano, so music was a big part of the Seder. They had other friends and family to the Seder, mostly adults. Less mayhem, good food and good music, lots of singing around the piano at the end of the evening. I thoroughly enjoyed those evenings during my later years at home. The Berrys always felt like family. Ray died young (he and Dad constructed the stand for my chuppah, borrowed from an artist friend for my wedding), Mildred remarried, but stayed in close touch. We exchanged letters until her death.

When I married, I learned Dan’s family didn’t know much about being Jewish. To them, Passover was a home cooked meal of Jewish food with a few blessings mumbled by their grandmother. I was very fond of and close to their mother and grandmother, but was nearly in tears during my first Passover of married life. It was nothing like my happy experiences with my own family with a formal Seder.

As we made friends in our married life, we were invited to other families who had nice Seders and that was great. Once David was born, I had my own little Seder, just for our small group, but it worked.

First attempt at Seder

The food is an acquired taste, but Jill, our nanny from Barbados, was a good sport about the gefilte fish, though she didn’t ask for seconds. As my family grew larger, I decided to grow my gatherings as well and invited neighbors with about the same tolerance for length of service as ours. Even an abbreviated Seder (and I tried several different Haggadahs before I found one that I liked) lasts about 45 minutes, going through each step. I started bringing in the food, but finally had it catered, as my group grew to number 15 in all and I led the service too. Those were fun times, before the kids went to college.

My house, 2000

I set a nice table and invited all comers, Jewish and non. We all had a good time, ate well and enjoyed each other’s company. Now we go to other’s homes, though this year, with social distancing, I thought we’d be alone. Since Dan doesn’t care for Jewish ritual, we would skip it altogether.

My darling and learned brother sent an invitation to join him and his wife for Seder via Zoom to me and various cousins and close friends in cities around the country. His children are in Brooklyn and Chicago. She even sent, in pdf format, a copy of the Haggadah they used. By some miracle, I had one of my own, though discovered that what he sent had been edited to his liking and he ran it full-screen, during the service, though I followed along on my iPad. We each had our own ritual food and symbols by our sides in front of the computers (my brother is a rabbi, and long-time professor at Hebrew Union College, the seminary that trains Reform rabbis), and each participated at our own home as he led the Seder. He has been teaching remotely for weeks now, so is good with Zoom. Annie set up break-out groups during dinner. The younger cousins got together. David even called in from London for a bit to say hi. Technology; got to love it!

Hours before my Seder, David sent me a photo of what he and Anna did (they are 5 hours ahead). She is a vegetarian, so made some appropriate substitutions on their Seder plate.

Seder plate from London

Annie and I began texting about a half hour before the service was due to commence. She normally has 30 people for Seder, extending her dining table all the way into the living room, using paper goods and plastic utensils. She commented how strange it felt to only have two place settings, put pulled out the good china and silver and lit her Arenstein grandmother’s candle sticks. We wash our hands multiple times throughout the service (as if anticipating these conditions). She said hand sanitizer would suffice. Here’s what their table looked like.

From Cincinnati

While we conversed, I took a photo of my setup. I don’t have a laptop computer, only a desk top, so it won’t travel to my kitchen table and I wanted to use my iPad for the pdf of the Haggadah (besides, my iPad is a mini), so I cleared all the space on either side of the computer and set up an old TV table (yes, the last of my mother’s), so I could have as much space around me as possible, as there are a lot of elements involved with the Seder. Here’s a shot of one corner of my Seder “table” (some items were on the other side of the computer). Just as Annie used her grandmother’s candlesticks, I have my grandmother, Belle Stein’s candlesticks, brought with her when she emigrated from Russian in 1906. So they are now over a century old. I love and cherish them. I am her youngest grandchild and it means so much to me that I inherited them. L’dor v’dor…from generation to generation. My matzah cover is a dyed handkerchief, made by one of the kids at our Temple nursery school, can’t even remember which child or how many years ago. It was lovely to pull it out again. My Kiddush cup was a gift from my father on my wedding day. We used it in our ceremony. The Seder plate was my parents. They bought it when they visited Rick in Israel in 1971. It has an Eilat stone in the center. Everything is full of memory and meaning. The daffodils were cut from my front yard that morning for a touch of spring on my table.

My Seder setup

I think everyone around the world tried a Zoom Seder on Wednesday night. We had technical difficulties and started late, but finally got in gear. As we waited for everyone to come on, I took a shot of our virtual community, though my nephews hadn’t joined us yet. Once we started, Rick had the Zoom tiles running down the side of the screen (not all were visible at any one time), with the text of the Haggadah running down the center of the screen, for all to follow along. He muted all except his screen so he and Annie could lead, comment and sing. At certain points, he asked for participation and each of us to unmute, individually, but due to virtual time lags, we couldn’t all unmute at once, so couldn’t sing together. We were only unmuted during dinner, though we came and went, depending where we were eating. I walked around the corner to my kitchen, as I couldn’t really eat soup in front of my computer, but it all worked quite well, considering. We had our food and Passover symbols in front of us to use during the service, so could each participate at the appointed time.

Rick & Annie are in the top left box.

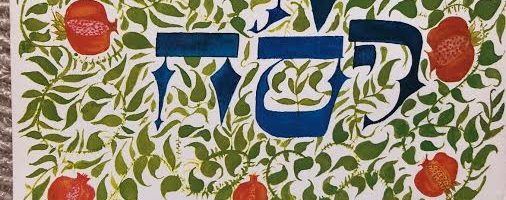

My brother chose to use the Haggadah edited by Herbert Bronstein, published by the Central Conference of American Rabbis, New York, as seen in the Featured photo. After the holiday candles are lit and the first of four cups of wine are drunk, we are reminded this is a time of birth and renewal and a poem is chanted from the Song of Songs which includes the verse, “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine” (roughly transliterated: ani la dodi, v’ dodi li; excuse my lack of Hebrew phonetics.) As my brother, who, like me, has sung all his life, I was overwhelmed.

Rick was ordained two weeks before my marriage. His first official act as a rabbi was, along with my long-time Temple rabbi, to co-officiate at my wedding, and he sang that song. Here we were, almost 46 years later, under these difficult circumstances, hearing my brother’s gorgeous baritone, chanting the same verse he sang to me and Dan on our wedding day. It took me up short, gave me comfort and joy, caused me to reflect, gave me hope.

For all the symbols of the Seder, they lead to the 10 plagues, brought down on Pharaoh so that the Israelites will finally be set free and allowed to leave Egypt. Each plague is bad, and Pharaoh claims he will agree, only to change his mind when each plague subsides, until finally, death is brought upon the land. His own household is not spared; his oldest son and heir is killed and he finally relents.

At this point in the service, we read the one word Hebrew name for each plague, stick our pinkie finger in our cup of wine and drop the red droplet on our plate, reminding us of the blood that is about to be shed. But before we read off the plagues, Rick interjected this thought: “For our people, it was a watch night; they were told to stay indoors for their own well-being while a plague rages outside”. The parallel was missed on no one in our virtual community. The text that followed, written in 1982, I found so powerful that I reproduce it here.

“Each drop of wine we pour is hope and prayer

that people will cast out the plagues that threaten everyone

everywhere they are found, beginning in our own hearts:

The making of war,

the teaching of hate and violence,

despoliation of the earth,

perversion of justice and of government,

fomenting of vice and crime,

neglect of human needs,

oppression of nations and peoples,

corruption of culture,

subjugation of science, learning, and human discourse,

the erosion of freedoms.”

My brother put particular emphasis on “perversion of justice and government”, and punched the words ‘science’ and ‘learning’ as he read these lines. I remind you that this Haggadah we used was first published in 1974, last revised in 1982. I turned the corner of the page in my own copy and wrote my brother’s introductory commentary in the margin. I wanted to be able to share it with this community. How thoroughly we can relate to the message today. But as we know from the psalms: light cometh in the morning. We must stay safe, ride out this horrible time and the abomination in the White House. We truly are stronger together, even if we are only together virtually at the moment.

Chag Sameach (Happy Holiday). By tradition, we end the Seder by saying, “Next year in Jerusalem”, but this year, I think we say, “Stay safe, be well, next year: back to normal, Vote Blue!”