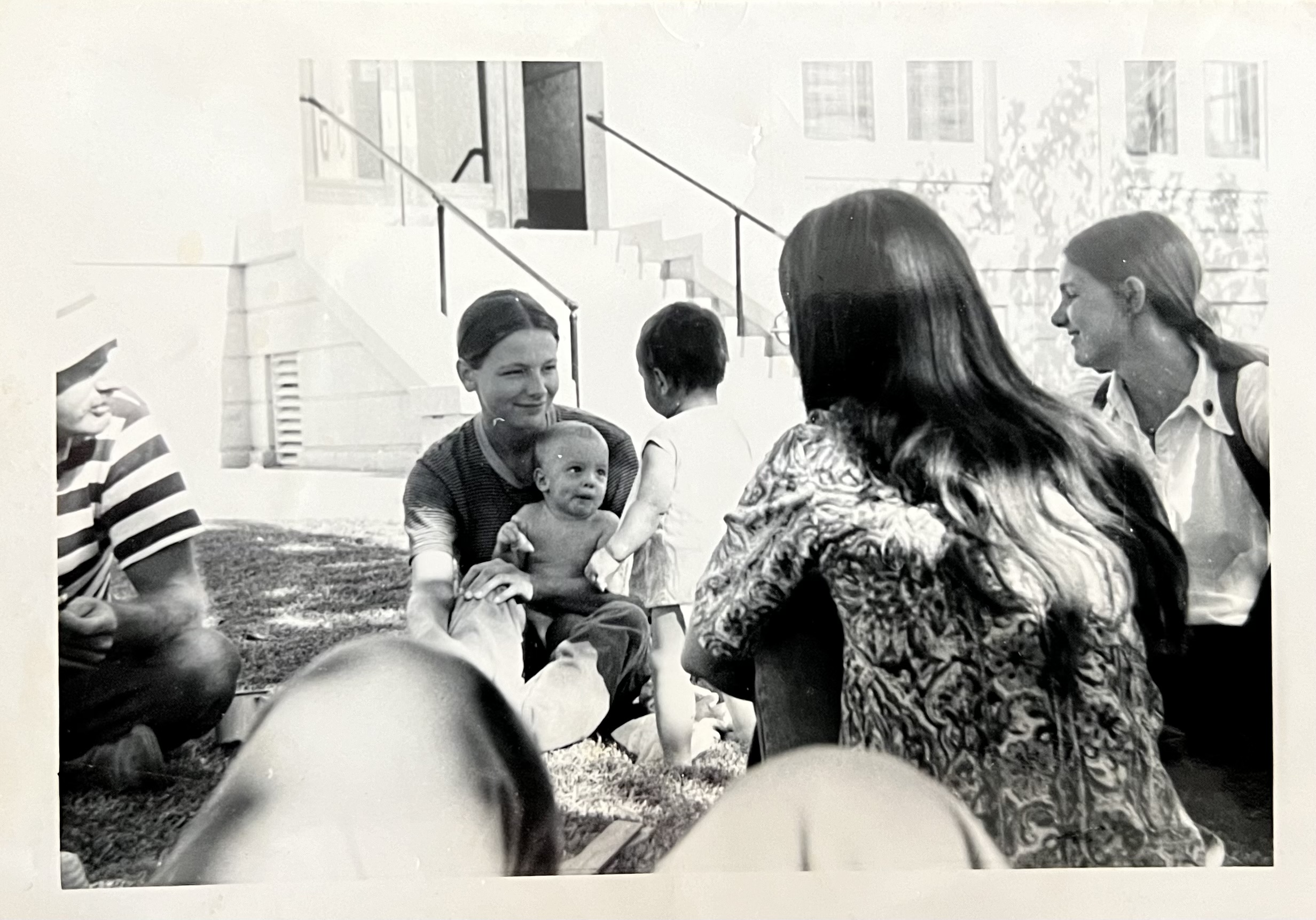

1974 El Centro outside courthouse after people arrested picketing in the melon fields

Calexico is hot, hot, hot in the summer. It sits at the southern end of the Imperial Valley of California and abuts its twin, Mexicali, on the Mexican side of the border. If you walk into the white light of day on the street, the dry heat can hit like an oven blast. The farmworkers would line up at 3 in the morning looking for day jobs, and then pick cantaloupes past when the heat should have driven them out of the fields. In 1974, the United Farmworkers Union was organizing in those fields, and had set up a medical clinic in Calexico to show its commitment to the workers’ health and welfare.

Instead of the usual “my name is” and “how are you” basics, I learned how to explain how many pills to take how often, with or without food, with cautions about dizziness, upset stomach or other side effects.

I eagerly sought out one of the $5-a-week summer volunteer opportunities at the clinic. A few years earlier, I had made friends with people working on the grape boycott and become inspired to get medical training I could use in support of just such a cause. And now, one whole year into medical school, I had a chance to make good on that idea.

Despite my education, I was far from being able to attend to patients directly. I spent the summer assigned to work out of the little windowless room we called the pharmacy in the converted house that was the clinic, dispensing pills. And learning Spanish.

The medications were ordered by some administrative staff, presumably under the license of the physician nominally responsible for the clinic. Someone else had already organized the shelves where the supplies were arrayed by type. My job was to keep the shelves in order, restocking as needed, and then counting out, packaging and labeling the prescribed pills. Since physicians could dispense medications, I suppose I was technically working as a physician trainee under supervision. I didn’t ask and, in truth, we were probably on the fringes of legality.

There was a plastic tray for counting pills. I would pour them onto the tray and use a wooden tongue depressor to marshal the proper number, meting out multiples of fours or fives over one edge into the attached plastic-topped trough. The excess pills would be poured back into the mother pill container; the rest would be poured from the trough to the patient’s pill bottle. Each bottle had to be carefully labeled with patient name, date, medication name and strength and number, prescriber name and instructions (in Spanish) on how to take the pills. I was very conscientious about that, even though it took a long time to print everything by hand. Then I had to instruct the patient verbally as well.

Although I knew French quite well and had embarked on a Spanish self-learning program with a grammar book, dictionary, and Spanish comic books, my language skills were limited. The patients lived mostly in Mexico and commuted across the border (much easier then), and some of the clinic staff knew almost no English, so it was a summer of immersive Spanish. Instead of the usual “my name is” and “how are you” basics, I learned how to explain how many pills to take how often, with or without food, with cautions about dizziness, upset stomach or other side effects.

I became quite familiar with common medications—amoxicillin, hydrochlorothiazide, metformin—the milligrams, color, shape and size of capsule or tablet. Cost was always foremost, so we stocked mostly generics, and stayed with the cheaper tried-and-true standbys. This was good training for judicious use of overhyped pharmaceuticals in later years. It also developed the excellent, if time-consuming, habit of assiduously explaining and documenting medications.

While we were in the clinic, UFW organizers were off in the fields, signing up members, protesting working conditions, and sponsoring rallies. We would sometimes support them by showing up at the courthouse when organizers were arrested, or by promoting and participating in rallies. We got to know some of the legal volunteers and staff, who shared the apartment complex with medical volunteers. The union was a many-layered undertaking.

Although I absorbed a lot of medical knowledge from my two months of dispensing pills, it wasn’t the technical skills I valued most. The camaraderie of the staff, the righteousness of our cause, and the gratitude of the patients was unrivaled. Two years later, more medical school training in hand, I returned to Calexico not to count out pills, but for a month of attending patients directly. It was my right path.

Wow, Khati, what a wonderful story about pills! You really walked the walk, supporting la causa in the best possible way. Your final beautiful sentence brought tears to my eyes.

Thanks Suzy. Good to see your presentation (and hear the songs) on zoom yesterday!

As always when you share stories about your good work, I think of the fortunate people you served so selflessly, in this case as a young medical student dispensing pills to farm workers in the heat in that makeshift Mexican pharmacy.

For that and for all you’ve done in your medical career since, thank you Khati.

Thanks Dana. Actually it was the poor farm workers out in the heat most of the time—at least our clinic had air conditioning! That little office was small and windowless but not baking 🙂

Khati! I so admire your long and varied activism! You write with such straightforward authenticity that you allowed me to feel each setting, from that hot, dry Calexico heat to the fields shimmering under the sun and the cramped, overworked spaces of the buildings that organizers are so often assigned to.

I was particularly moved by your final paragraph, describing the satisfaction and effectiveness of doing such “thankless” work, and how often organizing brings such heartfelt gratitude from all sides. I also appreciated how beautifully you described how that experience served as a stepping stone and affirmation of your calling. Brava, hermana!!!

Gracias Charlie. You know. I couldn’t imagine a better place to be.

What an enlightening educational experience you had in Calexico, Khati! I can’t imaging how on-guard pharmacists have to be these days to ingenious cons people use to get opioids. My doctor has already regaled me with some of those stories from what he has dealt with from his own patients.

I don’t recall we stocked any opioids in our little dispensary, or that there were issues (at least I wasn’t part of it). And we weren’t in the middle of an opioid epidemic either—fortunately. You are right that handling controlled medications can be a real challenge though.

It is so important to explain how to take pills and in what combination with other pills. Your experience with that aspect of medicine was invaluable.

I agree. I was always slow at least in part because I tried to be super-careful about staying on top of medications. No such thing as “just a refill” visit! You have to be sure med is doing its job, no bad side effects, is still needed, doesn’t need adjusting, necessary labs or exams done, is documented and so on. That can be quick but you have to at least a mental run-through of those considerations. And of course there are always other issues that arise. With elderly patients of multiple meds, particularly in longterm care, it can be good to work at “de-prescribing”—stopping unneeded medications.