All right, so you had a wet dream about another boy. Is that what knotted up your adolescence so badly? Look. The famous statistic is that one out of three males reaches orgasm with another male at least once in his lifetime. That’s from Kinsey. So relax. You didn’t even have physical sex with him, did you? You just dreamed about him, right?

All right, so you had a wet dream about another boy. Is that what knotted up your adolescence so badly? Look. The famous statistic is that one out of three males reaches orgasm with another male at least once in his lifetime. That’s from Kinsey. So relax. You didn’t even have physical sex with him, did you? You just dreamed about him, right?

I was going through a stage, right? I was SUPPOSED to hate little girls when I was a little boy.

RIGHT! Oh, RIGHT! I swear to you that I am desperately trying to keep this wicker-weave throne, to live up to the image all the authority figures have of me. RIGHT! Even if I had wanted to play out my—wait, strike that—even though I wanted to play out my fantasies—even though I longed to play out my fantasies—I would never, never have done so. And as a result, no one will ever find out that I have such fantasies. I’m clean, Officer. You’ve got nothing on me.

But now that we are on the subject, Officer, I can tell you a thing or two. I happen to know that some of the kids at camp were doing more than just fantasizing. Please don’t say I told you, but there was a lot of experimenting going on. And with some of the counselors, I think they weren’t just experimenting even, if you know what I mean.

Yes, I was only vaguely aware of it as I became an older camper—like the time Tommy and that counselor kicked everyone out of their tent and closed the flaps on a sunny day—but I was aware enough not to let any of those counselors give me back rubs. I was particularly cold to that one who couldn’t take his eyes off my body. I was so disgusted by the thought that this ugly man wanted to touch me, it made me shiver.

But, oh, what I would have given to be Tommy’s real best friend. God, how I wanted to be like him, to do the same mischievous, self-assured things he did, to have muscles and blond hair and a smile like his. Nothing in our relationship would be disgusting, nothing unmentionable. Just to be like the Hardy Boys, two blood brothers, two cowboys . . . that’s it: two cowboys.

In elementary school I had felt the same way about Chip Morgan. We would go up to his apartment after school and eat Oreos and watch TV, or play knock hockey, or play that board game called Baseball, where hitting and fielding are determined by a spin of the plastic spinner. Or Chip would put on his swim trunks and bathrobe, like Joe Palooka, and we would mess around with his boxing gloves, or wrestle, like we used to watch on Channel 9. Then his mother saw him that way once, in his trunks and bathrobe—well, I guess it was underpants, not swim trunks—and got angry and said never to dress like that again. But I was eight, nine, ten those years and too young to know what was going on. I just liked it.

I was going through what they call a stage, right? I was supposed to hate little girls when I was a little boy. I was supposed to hate those dance lessons we were all forced to take, aged ten, those multiplication dances where my ego required that I be chosen at any early round in the progression, while at the same time I was praying madly that if the progression caught me at all, it would be for the last round only so I would have to go bumbling around the floor just once, and then only while everyone else was too busy dancing, and maybe trying to sneak a feel, to have time to watch me bumble. Everyone else, of course, had things well under control, like that pitcher in color war.

I was going through a stage. Sure enough, young boys all knew: One of these days a little hair would start to grow in odd places (it did); the clerk would stop calling you “Miss” when you phoned in a grocery order (he did); muscles would begin to bulge all over your body (they did); and those little girls you had been ignoring would begin to drive you wild. I was waiting for those girls to start driving me wild, but I was very skeptical.

I was all of eleven when I first “knew” what I was, in a tentative, semiconscious sort of way, hoping to be proved wrong, but knowing for certain, down deep, that it was snake eyes for keeps. No fingers crossed.

My parents were having a party in Brewster: mostly businessmen, a few doctors and a few lawyers, some real estate types, their wives—the standard grown-up dinner party. Sports jackets and slacks: pipes, cigars, and cigarette smoke; the hubbub cresting, hushing momentarily, then rushing to crest with even greater force.

I was watching Superman in the den. My father passed through with one of his guests. He was saying something like: “I’ve read that, too; but ten percent just couldn’t be right. There couldn’t be that many people with homosexual tendencies. . . .” Something like that. Frankly, I am surprised I do not remember the exact words, because the incident itself I will never forget. That is all there was to it. They passed by; I sat there with my head aimed at the TV—but my face on fire with recognition. I knew, I’m not sure how, but I knew I was in that 10 percent. So that’s the word for hating dancing school, for not playing baseball, for admiring Chip’s athletic prowess, for the phony feelings, and lonely feelings, I sometimes felt.

It was hazy and vague, aged eleven. But I had gone off to camp the previous summer, and I was about to enter junior high school: I was being jolted into thinking a little, into becoming aware of myself. I no longer just looked at the picture of the Golden Gloves boxer in the magazine and liked it—I started to wonder why I liked it. And whether I was supposed to like it. And if not, whether I would stop liking it.

By the age of thirteen I was poignantly aware of what I was. But my inner shell of defense was impregnable. I had found out about myself, but no one else would ever find out as long as I lived. That stigma and keeping it a secret were the fundamental core of my mind, from which all other thoughts and actions flowed.

I would somehow cope. I would somehow enjoy hour after hour of cosmic depression, day after day, year after year. I knew what was happening now, and I spent most of my time writing programs for my defense department computer. You would never catch me spilling the beans in my sleep. You would never catch me electing art instead of science, playing Hamlet instead of tennis.

One ingenious defense was to remain as ignorant as possible on the subject of homosexuality. The less I knew, I reasoned, the less chance that I would start looking like one or acting like one. I wasn’t one, damn it Those people I saw on the streets with their pocketbooks and their swish and their pink hair—they disgusted me at least as much as they disgusted everyone else, probably more. I would sooner have slept with a girl, God forbid, than with one of those horrible people. Do you understand? I wasn’t a homosexual; I just desperately wanted to be cowboys with Chip or with Tommy.

So I never read anything about homosexuality. No one would ever catch me at the “Ho” drawer of the New York Public Library Card Catalog. Bachelor J. Edgar Hoover and his lifelong friend Clyde Tolson would have to be a lot more clever than that to trip me up.

[Somehow—”with a lot of help from a country that opened its heart and mind to being different,” Tobias writes—he sorted things out. Witness his speech, half a century later, at the 2012 Democratic National Convention.]

[Somehow—”with a lot of help from a country that opened its heart and mind to being different,” Tobias writes—he sorted things out. Witness his speech, half a century later, at the 2012 Democratic National Convention.]

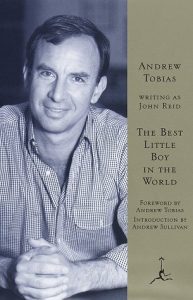

Andrew Tobias is the author of The Only Investment Guide You’ll Ever Need, the memoirs The Best Little Boy in the World and The Best Little Boy in the World Grows Up, and numerous other books, mostly about finance. (You can read his financial story Fearless Forecast elsewhere on this site.) He won the Gerald Loeb Award for Distinguished Business and Financial Journalism. Read his blog at andrewtobias.com.

“Cowboys” is excerpted from The Best Little Boy in the World. It was originally published under the pseudonym John Reid. Copyright © 1973, 1976 by John Reid and reprinted here by permission.

This story so vividly captures the turmoil of an adolescent’s mind, feeling new feelings and desires, anxiety over being “abnormal,” the need to fit in, and the resignation to cosmic depression. All of these are applicable to straight teens but even more poignant for gay teens. Glad to know it got better.

This is such a beautiful telling of a child’s struggle to make sense of his place in the world. I loved that you “weren’t a homosexual, but just desperately wanted to be cowboys with Chip or with Tommy.” So strong is the power of labeling that we learn to question our innate sense of self.

Beautifully written about the inner turmoil of adolescent struggle to fit in and discover one’s true self.