I loved reading about the very friendly skies while the little kids were asleep.

Read More

Babysitting with Coffee, Tea, or Me?

I loved reading about the very friendly skies while the little kids were asleep.

Read More

Each day I go to the convalescent home and walk in and see him sitting there and I am the ONLY person there that knows he was an amazing, genius of a man, one who had worked as hard as any successful man could and one that raised a family, he was the most loving husband a woman could know and a man that cared about all living things and made sure nobody ever needed and now there he sits with Alzheimer’s.

Read More

I am a historian on the interstellar environment Samsara, circa 3200. I explore the many time capsules that were loaded aboard the craft before we departed earth. The capsules were loaded helter-skelter in the pre-launch rush, but I take great delight in randomly sampling their contents.

Today I found several intriguing artifacts that had worked themselves up through a data capsule from the early Anthropocene* era. The artifacts featured images, precisely pressed into the porous surface of compressed wood pulp, known as paper. Paper came from the time of trees, when men — only men — toiled mightily to fell the trees under the beauty of eco-systems called forests. I felt intrigued but sad: the action seemed contradictory, that people would work so hard to destroy natural beauty. There must have been a reason.

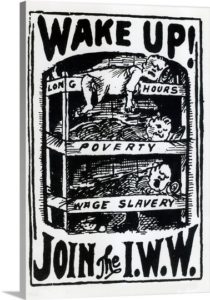

After analyzing the graphics for days and pondering, I began to understand that the images told a story from a time of work. In this work era (circa 1900 – 2200) , people competed for the right to join authoritarian hierarchies where they were ordered to perform mind-numbing, repetitive, sometimes dangerous acts in exchange for currency. Currency, often called “wages” was a medium designed to represent use value — as if people’s worth depended on how much repetitive or dangerous work they could withstand.

After analyzing the graphics for days and pondering, I began to understand that the images told a story from a time of work. In this work era (circa 1900 – 2200) , people competed for the right to join authoritarian hierarchies where they were ordered to perform mind-numbing, repetitive, sometimes dangerous acts in exchange for currency. Currency, often called “wages” was a medium designed to represent use value — as if people’s worth depended on how much repetitive or dangerous work they could withstand.

The people who worked received currency which they could exchange for commodities — food, clothing, shelter, mobility — and services. None of these commodities were morphed into their lives as they are today.

As I studied the data capsule’s graphics, I began to question how much we take for granted about our natural and civil rights. These graphics also suggested that, if groups or individuals were unable to perform these “works,” they would be cast out of society and even be allowed to starve or die of disease.

As I studied the data capsule’s graphics, I began to question how much we take for granted about our natural and civil rights. These graphics also suggested that, if groups or individuals were unable to perform these “works,” they would be cast out of society and even be allowed to starve or die of disease.

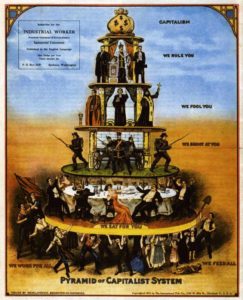

The graphics also revealed that currency was unequally distributed. It may seem contradictory, but many individuals or small groups could gather enormous amounts of currency, more than they could “spend,” or “exchange” for commodities. These individuals and groups were often connected — through a synthetic form of symbiosis called hegemony — to those who decided who would work and who would not. These decisions were often based — not on ability — but on a potential worker’s placement in the hierarchy, their facility within narrow intelligence spectra, and even physical appearance.

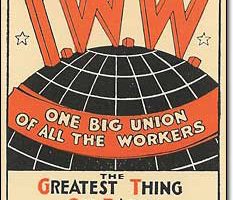

The workers (men, women, and animals who worked, as the word suggests) seemed to have little or no power over how many “wages” they could earn. The graphics seem to suggest that the worker people began, over centuries, to gather together into a critical mass they called “One Big Union.” They considered these gatherings to be powerful.

The workers (men, women, and animals who worked, as the word suggests) seemed to have little or no power over how many “wages” they could earn. The graphics seem to suggest that the worker people began, over centuries, to gather together into a critical mass they called “One Big Union.” They considered these gatherings to be powerful.

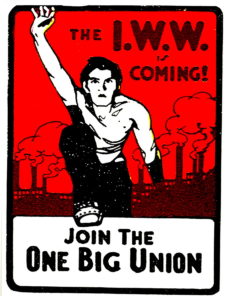

Although the first worker gatherings began centuries earlier, the One Big Union group represented in the posters had evolved into the International Workers of the World or IWW, possibly pronounced “Eww.”

The Ewws seemed at times to stand at a crossroads. Some wanted to demand wages called “fair pay” suggesting justice or satisfaction could be enjoyed by toiling for currency. Others wanted, as far back as these centuries-old ancestors, to abolish the entire system of currency, as if they were predicting our own world.

The Ewws seemed at times to stand at a crossroads. Some wanted to demand wages called “fair pay” suggesting justice or satisfaction could be enjoyed by toiling for currency. Others wanted, as far back as these centuries-old ancestors, to abolish the entire system of currency, as if they were predicting our own world.

I have not yet determined how much meaning they placed in this toil. Certainly there must have been times, as we enjoy now, when people either inherited or fought for the right to health, beauty, imagination, and creativity. Some may even have taken meaning from doing these dangerous, repetitive, or mind-numbing jobs. However, for many, if you lost your work, your life would have no meaning. Can you imagine the jeopardy that suggests?

I have not yet determined how much meaning they placed in this toil. Certainly there must have been times, as we enjoy now, when people either inherited or fought for the right to health, beauty, imagination, and creativity. Some may even have taken meaning from doing these dangerous, repetitive, or mind-numbing jobs. However, for many, if you lost your work, your life would have no meaning. Can you imagine the jeopardy that suggests?

If you’re interested in these glimpses into our ancestors’ past, I urge you to approach those ancient times with respect and to understand how completely we are accustomed to enjoying health, beauty, imagination and creativity as our human and animal rights.

As I explored other glimpses of this One Big Union, its heritage and legacy, I had the eerie feeling that I was missing a cross-current that may have been present during this time of work. Is it possible that they found joy and love amidst these cruel conditions? Is it possible that people took pride in gathering together to fight for work? Could they have gained satisfaction or a sense of accomplishment from participating in this work for survival?

Life is complex. History offers lessons for the present. Even far up the ages, with all that has changed, it seems as if work may have brought with it, a certain nobility. I must explore further this great and long-lasting battle. I can only hope that deeper examination will tell us much about our past… and our present.

Life is complex. History offers lessons for the present. Even far up the ages, with all that has changed, it seems as if work may have brought with it, a certain nobility. I must explore further this great and long-lasting battle. I can only hope that deeper examination will tell us much about our past… and our present.

# # #

*An·thro·po·cene — the geological age during which human activity became the dominant influence on climate and the environment. Geologists estimate that the anthropocene age began between the mid-18th century and 1950, EWT (Eurocentric World Time).

I interviewed for a year, but it was a start-up and they weren’t ready to hire salespeople. I was looking to leave the software company I worked for and come to this one, as the product was a good fit with what I already knew. In fact, it could serve as a friendlier front-end to my current product and I was the perfect person to introduce it to the world, having been the most successful salesperson at my current company.

When they were ready, they hired three of us; Mehmet, Drew and me. We all had the same offer letter and started the same day. But Mehmet’s territory was the whole East Coast except New England. Drew had the rest of the country. I had New England including greater New York, but not the city itself. I protested to the president of the company. No way was that fair, but he said salespeople always wanted more territory and just do my job. I also was not allowed to hold Hardee’s Food Systems in Rocky Mount, NC. They asked me to call as soon as I got to the new company, since they already wanted my new product. Mehmet made the call, got the sale and told me they had signed strictly on the basis that I was with this new company. I got no credit.

I also became pregnant a month after joining this little start-up of 15 people. I didn’t tell anyone, but did have “morning sickness” all day. People at the office became annoyed when I ran to the bathroom to throw up, thinking I was contagious. I finally had to confess that what I had, they couldn’t catch! It didn’t take long for them to figure things out. Within a few months, I felt better and had a few good leads that I pursued. I don’t chase my tail. I am good at screening out tire-kickers and only chase down leads that I think have potential. I am not afraid to ask for the order and am good at closing business. I also set up a strategic partnership with Arthur Andersen.

I grew bigger and bigger. I put on 42 pounds in total and worked until two weeks of my due date. My manager had recently been through a nasty divorce and I think that affected his view of women. He didn’t take a shine to me, a strong, successful woman. He wanted to stay close to home before the 4th of July holiday, so asked to come on a call with me to Combustion Engineering in Stamford, CT. He drove, I did the sales pitch. He had never seen me in action, though it was one month before the start of my maternity leave. The call went well. He was impressed. Really? Did he think I would be incompetent?

My clients from Westinghouse referred to my maternity dress as something made by “Omar the tent-maker” (couldn’t say that today, but this was 31 years ago). The Featured Image is the company picnic. I am the curly-haired (it’s a perm) big-bellied lady on the right. The president is wearing red shorts in the center of the photo, looking to his left. My manager is kneeling to the left of me (actually, my right side), with the receding hair line.

I closed business with Westinghouse, Combustion Engineering, Gillette…I don’t even remember who else. Aetna was in the works. Mehmet closed it and I did get credit for that. At the time I went out on maternity leave, the amount of stock we salespeople were being granted still had not been voted on by the Board. I, personally, was responsible, in 10 months time, for 60% of the revenue of the entire company. I had planned to take a 4 month, unpaid maternity leave.

I left on August 2, 1985. A few days later, the letter arrived telling me the stock grant. It was 40% smaller than my two male colleagues. I called the president. He lived a few blocks away. I asked if he could come by for a talk. I asked why, given my actual performance, I had been voted less stock than the other salesmen. He told me my manager hadn’t made a strong case for me in the Board meeting. He went on to say that I had fewer sales calls than the others and my pipeline wasn’t as long, and I seemed to be in the office more. Of course I was. I could make a call in the morning and still come in, since I had the LOCAL territory! But I had CLOSED MORE BUSINESS! That was irrefutable.

I talked to a lawyer friend. She said I had a clear case of discrimination, but judges hated cases like that (1985) and if I ever wanted to work again, I should just walk away, which is what I did. I stayed home with David, who was born on August 20, for 18 months. I really don’t know what happened to the software product I sold, but some of the principals in the company have gone on to other successful ventures. I took my lumps and added to my feminist cred.