My church youth group pressed into Pam like clowns into a VW bug.

Read More

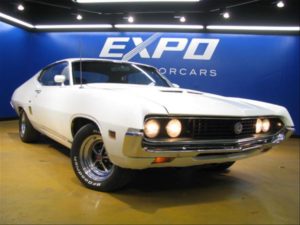

We called her Pam

My church youth group pressed into Pam like clowns into a VW bug.

Read More

My First Ride, a 1970 Ford Torino, a better car than I deserved that I treated with less respect than it deserved. I wouldn’t have had this car if it wasn’t for my brother Gene and my dad. It took me to concerts, to the beach, hiking, camping, out to the lake and many other adventures with my friends.

I wish i had had taken better care of this car and kept it to this day. It was worthy. Whenever I see one I harken back to the days of driving far too fast and scaring the snot out of my friends.

I usually had Queensryche Operation Mindcrime or Metallica Master of Puppets blaring on the radio. We would take it out and cruise McHenry on a Friday night, or pile in to it during lunch time at school and grab burgers at Scenic Drive Through.

There were countless burn outs on Paradise Rd and high speed runs down highway 132, it’s a miracle I didn’t get anybody killed or even marginally hurt. There was one time I accidentally spun the car 720 degrees on a wet road and somehow maintained control. I was a freakin idiot and a higher power must have been watching over me to save me from my own stupidity.

Many years and many cars later this one holds a special place in my heart that it will always have.

We lived in the Oakland hills, and bus service was minimal - everything was far away.

Read More

This excerpt from Even in Darkness occurs when Klare returns from Theresienstadt, the concentration camp, to reestablish a life in her home town of Hoerde. She begins to lose those she'd fought so hard to save, not realizing that redemption is just around the corner.

Read More