Though not an art history major, I’ve loved looking at and learning about art since I was a small child. I tend to be very sensitive to all forms of external stimuli, which makes me open and vulnerable to various forms of creative arts and I enjoy most.

For example, I have always loved the story of Romeo and Juliet. (I first saw it performed as a 10 year old, while visiting my brother at the National Music Camp – he was a Capulet servant, but the girl who played Juliet went on to a professional career, playing opposite Jack Lemon in his Academy Award winning role in “Save the Tiger”.) I desperately wanted to perform the lead role at some point in my life. The closest I came was doing one of her monologues in Speech Class in college. But my mother took me to see the Stuttgart Ballet perform their version (set to Prokofiev’s dramatic music) when John Cranko, their genius leader, was still alive and I was still in my teens. Marcia Haydée, one of the leading ballerinas of her day, danced the role of Juliet. Much as I love ballet, it does not easily move me, yet in this version in the death chamber scene, Romeo dragged Juliet’s lifeless body around and had me weeping. I could feel Romeo’s anguish for his lost beloved and it moved me to despair too.

I have sung my entire life and am frequently moved by the music, as I wrote about some time ago: Gotta Sing .

I did take some art history courses in college, with a speciality in Renaissance art. My son took a painting course in Italy in the summer of 2002, but of course, looked at the masterworks too. I told him to “see the art with my eyes”. He brought me a book on Giotto, the father of 3-point perspective.

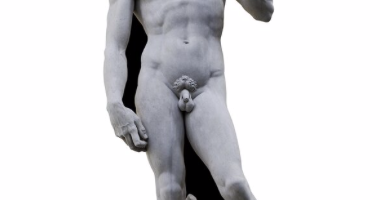

We finally got to Italy in 2011, touring Venice, Tuscany, Florence and Rome. It was everything we’d hoped for, with wonderful guides in Florence and Rome. When Lorella, the Florence guide, took us into L’Accademia it was a quiet morning. We quickly walked through the entry galleries into the grand salon that holds Michaelangelo’s masterwork: The David. It truly took my breath away. Of course I’d studied it, seen a zillion photographs of it, but being in its presence, being close to it, was something else entirely and I welled up, just by the magnificence of it. Lorella looked on with approval. She could tell that I felt it in my bones, that I was moved beyond words. A mere mortal had sculpted this from sheer rock. I stood in the presence of genius and was humbled by it. (And the teacher in Florida who thinks this is pornographic and the teaching of it should be banned should sit in a corner with a dunce cap on; her thinking is from a different century. She should not be allowed near impressionable children.)

I’ve been active at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University for over 33 years and on its Board of Advisors for something like 25 years. The Rose was selected to host the U.S. Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, the granddaddy of art shows. Mark Bradford did all the artwork in our pavilion, as well as working with prisoners at a local prison to teach them how to make handbags that were sold locally. They kept some of the proceeds, some benefitted indigent people in Venice. That made an impact.

I spent five glorious days at the vernissage before the official opening of the show. With our interim director and several Brandeis art history professors and curators, we had insider access to all the exhibits with great people to explain all. We could wander off anytime we chose and our group, along with another museum (where our former director had now become the director) hosted an incredible gala at Cipriani, overlooking the Grand Canal. Extraordinary!

One artist really grabbed my attention. On May 11, 2017, Kristin Parker, our interim director took us on a tour through the Arsenale, a huge space full of invited artists. We stopped to see Lee Ming Wei. He is a performance artist. He collects old clothing from people and he and his assistant stitch up the holes in the clothing, thereby healing, or making the owner “whole”. The thread from the patch is then unspooled and attached to the wall near their workspace, making a web of thread – its own form of art that grows and changes.

Kristin knew this gentle man and spoke with him at length about his process and philosophy. Something about his story really struck me. He was a Chinese refugee who had lived in Paris most of his life, so he understood pain and displacement. The idea that by stitching up these torn garments, the owners could be healed really gripped me and I again welled up. Kristin noticed me – “Betsy’s having a moment”. She took me in her arms and comforted me.

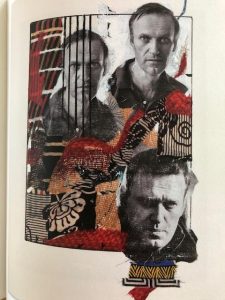

Last autumn, the Rose hosted a one-man show for Peter Sacks, a brilliant poet and painter who emigrated from South Africa as a young man and now lives full-time on Martha’s Vineyard. The show was called “Resistance”. He painted collage-style portraits of historic figures from across the world, some still with us, most deceased, who have had the courage of their convictions to resist oppression or the status quo and promulgate change. The portraits depicted everyone from Harriet Tubman to Nelson Mandela to Alexei Navaly. They also included audio recordings of some of their remarks, read by famous people, projected into the gallery in a great wave of sound, though through an app on your phone, you could isolate each person’s personal narrative. As I write this, on August 4, 2023, Alexei Navalny, who has been imprisoned in Russia on trumped up charges since January, 2021, was sentenced to 19 additional years for “inciting extremism, rehabilitating Nazism”, and other ridiculous charges. He is trying to point out Putin’s corruption and is being silenced. His daughter, Daria, now a student at Stanford, was at the Rose opening last fall. She took in all the portraits solemnly and quietly said, “So few of them survived”.

Isn’t this what we all need these days? To have a moment, perhaps be comforted – “healed”; or open our eyes and learn something new? Great art should inform, teach, ask us to be vulnerable or even uncomfortable and challenge us. That should be what art can do, if we open ourselves to it.