[I wrote this piece for the Retro prompt “Gardens,” but I’ve posted it here to celebrate the salmon that reinhabited the Mattole watershed as a form of recycling. — cd]

I wrote this piece for the Retro prompt "Gardens," but I've posted it here to celebrate the salmon that reinhabited the Mattole watershed as a form of recycling.

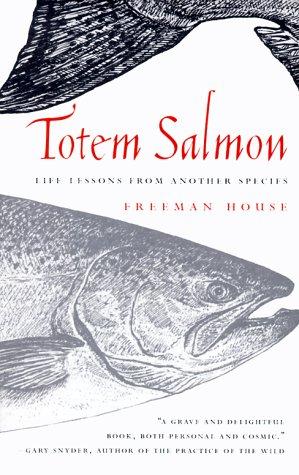

“…we have lost previous models of a more elegantly balanced life among humans.” — Freeman House, Totem Salmon

As I child, I grew championship cucumbers on a septic tank. I grew apples and corn for farmers. I grew communal gardens in Massachusetts and California. I’ve grown hot peppers and marijuana together; they are the best of friends. You can put your pot-sticky fingers to your nose and inhale but never, NEVER touch your face after you’ve cut an orange habañera pepper. This simple advice is typical of the kind of lessons one can learn from gardening, que no?

I’ve also had the opportunity to walk through a different kind of garden, one with roots in land and water, a garden created by the earth gods and goddesses and cultivated for millennia by indigenous people, those who lived on the edge between hunting and gathering and planting and harvesting.

Freeman House was a salmon fisherman, writer, and ecological thinker who lead the efforts of a group of people who set out to recreate a garden from the main course and tributaries of a California river and the land that surrounded and supportedit. Not a garden in the standard sense of the term, but a garden, nonetheless.

In the late 1960s, I lived in San Francisco with an extended family of utopian anarchists who set out to explore new ways to live on the land outside the city. They wanted to extend our notions of change to the countryside, where they could see the scars of industry that had “tamed” the wilderness.

In 1975, a small group of these San Francisco artists, activists, and adventurers moved to a hillside above the Mattole River along Northern California’s Lost Coast, in Humboldt County. They had seen firsthand how the Mattole’s complex and fragile watershed had been eroded by overgrazing and clear-cut logging. As they became more intimate with the land they loved, they saw how the salmon suffered from the destruction “of a place” — the creeks and small tributaries that fed the Mattole. In the words of Freeman House:

The very roots of the word ‘indigenous’ mean “of a place.” But…the relatively recent Industrial Revolution have been so successful that … we have engaged in a process of purposeful and systematic forgetting; we have lost previous models of a more elegantly balanced life among humans, and we have convinced each other that it is fruitlessly utopian to imagine any other way of life.”

Freeman and his brothers and sisters set out to reinvent “a more elegantly balanced life” in a unique garden of earthly delights, using indigenous means and ways of thinking.

Salmon hatch upstream at the headwaters of small creeks and streams and as youngsters, swim downstream to the sea. There, for two years, they become deep water creatures, roaming for thousands of miles, growing into the powerful and intuitive animals who return to the exact same creek or other tiny tributary where their parents had laid and fertilized their eggs to complete the cycle of life.

In the Mattole, the logging and overgrazing had filled these tributaries, making it near impossible for the adults to return to their birthplace. Confused, they often died during their frustrated journey upstream.

The Mattole family followed the way of the area’s indigenous people, who considered the salmon to be a life force. They reasoned that, if the bioregion (the watershed of the Mattole) was ill, the salmon would be ill. If they made the watershed a healthy bioregion again by clearing the streams and tributaries, they would make the salmon healthy again.

They set out to do just that, to restore the garden that had developed naturally in the Mattole bioregion. They began a long campaign to convince the community of ranchers and loggers to do the impossible — pay attention to the health of the Mattole watershed. At the same time, the family set out to restore the salmon and their migration by collecting them in hand made traps, incubating their conception and releasing them. After years of patient work, the Mattole family began to win cooperation from local ranchers, loggers, and even the Bureau of Land Management.

Nothing is perfect, nothing ever lasts, except an abiding love for the wild beauty of the salmon. Today, generations of “gardeners” have followed in the footsteps of Freeman house to sustain the wild beauty of this noble creature, the totem salmon and the garden it lives in.

# # #

*Totem Salmon is also the title of a book by Freeman House, who describes in detail the Mattole River salmon restoration project. You might find it of interest.

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Fascinating! I am intrigued by all the stories hinted at in your first paragraph – sounds like you could write several more tales about gardening. The Mattole River section of your story is all in the third person, so I’m wondering if you were part of that group of salmon caretakers. You have written previously about your time on the Lost Coast, but I don’t know if it was in 1975 or not.

Was not a Petrolia dweller, playing and doing theater in S.F. This scene and the salmon project was umbilically linked to brothers and sisters in SF.

Thanx Charles your the enlightenment and for reminding us there is no Planet B.

They just found hints of oxygen in Venus’ cloud cover. Does that count?

Can we book the next flight if the unthinkable happens here?

Many have suggested such a possibility, Although I’ve heard it said that we need more than oxygen to survive.

This is so interesting, Charles. I am forwarding this link to a good friend who is deeply involved with environmental issues. I wonder if she knows about this.

These were — and are — fascinating people. Many are now engaged in worldwide travel with a company called The Reinhabitory Theater.

I loved learning about the Mattole River and Lost Coast, and it’s gratifying that the actions of Freeman House and others seemed to have had some lasting impact. Our oceans certainly need our curation and love.

The words and work to seem to be expanding. Renewable wild salmon areas such as Bristol Bay off the coast of Alaska have withstood even the onslaught of Trump. Thus far… See Pebble Mine, Bristol Bay.

You speak in a mythic voice here, giving the image of generations of caretakers of the salmon. You weave a wonderful tale of caring for these fish. Thank you for sharing this journey. As Suzy points out, it is not clear if you were along for the ride or not, but we learn a lot along the way.

No, this salmon project was a spin-off of the Diggers in SF. I was a part of that family and spent much time up there. My gypsy converted school bus joined a caravan of trucks that formed the shelter for the first settlement of the family engaged in the salmon project, ca 1975.

As Betsy mentioned, you bring a mythic voice to this tale that somehow makes it lyrical. Respect and stewardship…critically fundamental, yet in imminent danger under the current administration.

Thanks, Barbara. I had no idea I was generating a mythic voice, but I think the scope and scale of the project has its own authentic mythology. I would change your last observation to read, “yet in perpetual danger.” The agent orange is only the most recent obstacle to efforts to re-balance even the smallest elements of our ecoverse. Mister Natural, astride an R.Crumb manufactured red tractor once raised his finger and said, “twas ever thus.” Although I usually disagree, the cosmos changes constantly, never repeated, those salmon have been swimming upstream, or more properly, not been allowed to swim upstream, from ‘way pre the orange assault.

Thanks for reposting this, since I missed it the first time around. The attempts to restore watersheds and salmon habitat have certainly had some successes after the work in the Mattole watershed (and I hope and assume that watershed has continued to improve since the 1970’s). There has been an active creek restoration movement in the Bay Area (we were Friends of Sausal Creek in Oakland), and salmon have just this year finally made it all the way from the ocean, up the Columbia and Okanagan Rivers, to Lake Okanagan, thanks to efforts of indigenous groups and other friends. The work continues, and so much more to do.

The work does continue, Khati. I understand there has been conflict along the Columbia over indigenous fishing rights on the Columbia. I’m guessing our amazing Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, has the restoration efforts on her agenda. And, as much welcome good news, her previous district in New Mexico has overwhelmingly voted in a woman Democrat.