“Trust but verify.” So said President Reagan vis a vis the Soviet Union and nuclear weapons.* A manifest contradiction, I believe, at least as to “real” trust. “Real” trust, as opposed to, say, transactional trust – the more superficial trust found in ordinary, day-to-day financial and mercantile exchanges. Real trust is built upon a shared fundamental honesty. In such instances verification makes no sense. It is implicit in the relationship. Unless, of course, the relationship is a mirage. Two experiences inform this view, the first revealing and the second devastating.

I discovered that those key staff members I had interviewed had withheld documents and flat-out lied to me, to my face. People I knew and trusted.

I was General Counsel of a conglomerate of investment management firms. In February one year I learned of a potential issue at our Chicago subsidiary and launched an internal investigation, reviewing documents and interviewing key staff members, including the CEO of the firm. I determined that there had been some transactions that seemed to violate federal securities law but they involved former, not active clients and were several years in the past (and prior to the conglomerate’s acquisition of this firm.) I informed my boss, the CEO of the conglomerate, of my findings and said that I would add appropriate training at the annual compliance meeting at the end of the year. But in August I received a call from someone who identified himself as an Assistant US Attorney in Boston. He informed me that he had a Grand Jury subpoena for my company and asked where I wanted it sent. Probably the worst day of my career. It was clear that it pertained to the matter I had investigated internally. I wondered what I had missed, what errors I had made, etc. I retained outside counsel to investigate and two years later they reported significant violations of securities laws that involved the Chicago CEO. An SEC enforcement action ensued. I discovered that those key staff members I had interviewed had withheld documents and flat-out lied to me, to my face. People I knew and trusted. As a result, my internal investigation was worthless. I would not call myself naïve, but I was shocked that colleagues would do such a thing and was profoundly embarrassed.

A few years later I had left the conglomerate and was doing securities and commodities compliance consulting on my own. A colleague that I had known and worked with for about six years approached me about joining forces with him and another colleague. “Jack” was a contemporary with equivalent experience to mine. He had worked at the SEC for some years and later with a major player in the investment management world. We launched our firm. Oftentimes in conversation Jack talked about some significant personal financial issues, including dealing with the fallout from identity theft. He regularly made clear that he was far from financially secure. At one point in the midst of a regular three-way business discussion among us partners he mentioned that his daughter, who was getting married soon, cried herself to sleep every night because it seemed that he, Jack, would be unable to fund a reception. Having experienced more than one failed marriage and knowing how difficult it was even in the best of circumstances for some marriages to succeed, I offered to lend Jack a fairly significant sum so his daughter could “start out right”. Jack gratefully accepted. Sometime later it was clear to me that our business venture would not succeed as such, so I opted out and went back to working on my own.

Not long after I did, and as a result of my communication strategy regarding that development I got a call from “Bill”, the owner of a firm where Jack had worked when we first met and for whom I had subcontracted several engagements. I knew that Jack’s parting from Bill’s firm had been contentious and that there was ongoing litigation. Bill proceeded to summarize what Jack had done – and failed to do – when Jack worked for Bill. And what had transpired in Jack’s subsequent employment with “Ted” in Florida. It was all of a piece: Jack was a master at skimming tens of thousands of dollars in loans and advances, all obtained under false pretenses. The “identity theft” story? A tall tale. E-mails obtained by Bill’s attorneys included an exchange wherein Jack, having scored another fraudulent windfall, crowed “identity theft does it again!” to which his son, an accomplice, replied, “Dad it’s just theft.” I was more than a little surprised. And then Bill described how Jack had even come to him with a sad story about needing to find a loan shark so he could fulfill a promise to his son, who was about to get married, to fund his honeymoon. Bill had taken pity and loaned Jack the money. Gulp. In an instant it became clear to me that Jack had scammed me, too. Jack, someone I had known, worked with and even associated with over a long period. I knew I would never see the money owed, but the shock of that realization paled beside the shock and devastation of the betrayal.

Dante wrote that the hottest places in Hell are reserved for those who, in a period of moral crisis, maintain their neutrality. Not so. The hottest places in Hell are reserved for those who, through dishonesty, breach relationships of trust for personal gain.

– – – – – – – – – –

* Those who watched the terrific HBO miniseries Chernobyl may recall that one of the characters mentions that this was a “borrowing” from a Russian motto/saying.

Retired attorney and investment management executive. I believe in life, liberty with accountability and the relentless pursuit of whimsy.

Thanks for the great story, Tom, starting with the perfect title.

Having been a lawyer for big accounting firms for years, I have myself had to deal with a multitude of financial frauds, SEC and Grand Jury investigations and the like. So your story particularly resonated with me. I’d like to think I never got fooled — by my own clients at least — but I can never be sure of that. I can easily imagine how horrific a feeling it must be to learn that. That said, I would think that Jack’s betrayal of you would be even more painful. So I salute you for your own honesty in sharing these horrific stories with all of us.

Which reminds me, pal, I may need a little help if one of my daughters finally gets married….

Sure thing. Provided I have funds left over after buying this great bridge a good friend told me about.

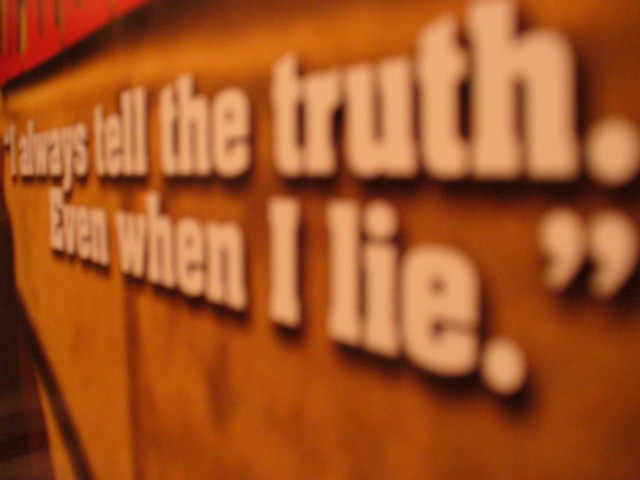

Thanks for this story, Tom. I love your title and the quote in your Featured Image. Had to google the quote to find out it was from Al Pacino in Scarface, a movie I’ve never seen. The two experiences you describe are horrible, and I can’t even imagine what that would be like. Your description of who should get the hottest places in Hell is perfect, I think even Dante would agree if he heard your stories.

Thanks, Suzy. I suspect that place is severely overcrowded.

Tom, what traumatic experiences of lying in the business world, especially involving people you trusted. I wonder if you, or anyone commenting for that matter, has ever been asked to lie in a corporate situation. This happened to me twice. The first time was in creating advertising for a software product that the company wanted to say was used for one purpose when it actually was being used for another (I resigned the client). The second was when a vice president instructed me to lie on an FDA form to claim some software had been validated when it hadn’t. I refused, since that lie could mean jail time, and a few weeks later the VP fired me (out to the parking lot, the whole bit). He subsequently was fired and I was asked back, so not only was honesty the best policy, it all worked out in the end.

Marian I’m glad it worked out; it’s comforting when doing the right thing is rewarded. To your question, I don’t recall ever being asked to lie in a corporate situation. As an attorney lying puts one’s license at risk of suspension or revocation. Whether or not that discouraged colleagues from asking me to lie or not I don’t know but I’m pleased no one did. Private practice was another matter: never directly unambiguosly asked to lie but attempts were made. By a handful of persons who quickly became former clients.

Betrayal in business is bad enough, but being scammed by a friend who played on your personal relationship and feelings — that’s beyond awful. So sorry you had to go through this experience, Tom.

Thanks, Laurie. In the “making lemonade” department: I spoke on panels and in client training sessions about this “affinity fraud”. I always asked the question, “do you think you might fall for something like this? Let’s have a show of hands.” Typically about half would raise their hands. All women, no men. Then I would ask, “do you think that someone like ME might fall for something like this? Let’s have a show of hands” No one ever raised a hand. And then I’d tell my story. I think everyone got the message.