John and Stella

John thought about Stella the whole way. It took the whole day to ride the train from the city where he lived to the town on the coast where his grandmother would meet him. As he scanned the platform for his grandmother’s canvas hat, John wondered how big Stella would be. He wondered what color she would be painted, and if her name, Stella, was already there on her stern in big curving letters.

A story about a boy, his grandmother, and a boat.

When John shook his grandmother’s hand they way she liked him to, he barely noticed that it seemed smaller and bonier than last year. And when she called him John, instead of Junior the way everyone else did, he didn’t mind. He was getting older after all, maybe she was right, it suited him, John. It sounded like the name of a boy who was old enough to have his own boat, not just a little kid anymore.

They walked together through the shady lanes of the town, down to the dock, but John wasn’t listening to the way her voice sounded rough and tired, how it skipped a little when she talked, like stones skip over the slow water in the cove before the tide turns. John was thinking about Stella and he couldn’t wait to get to the island to see her.

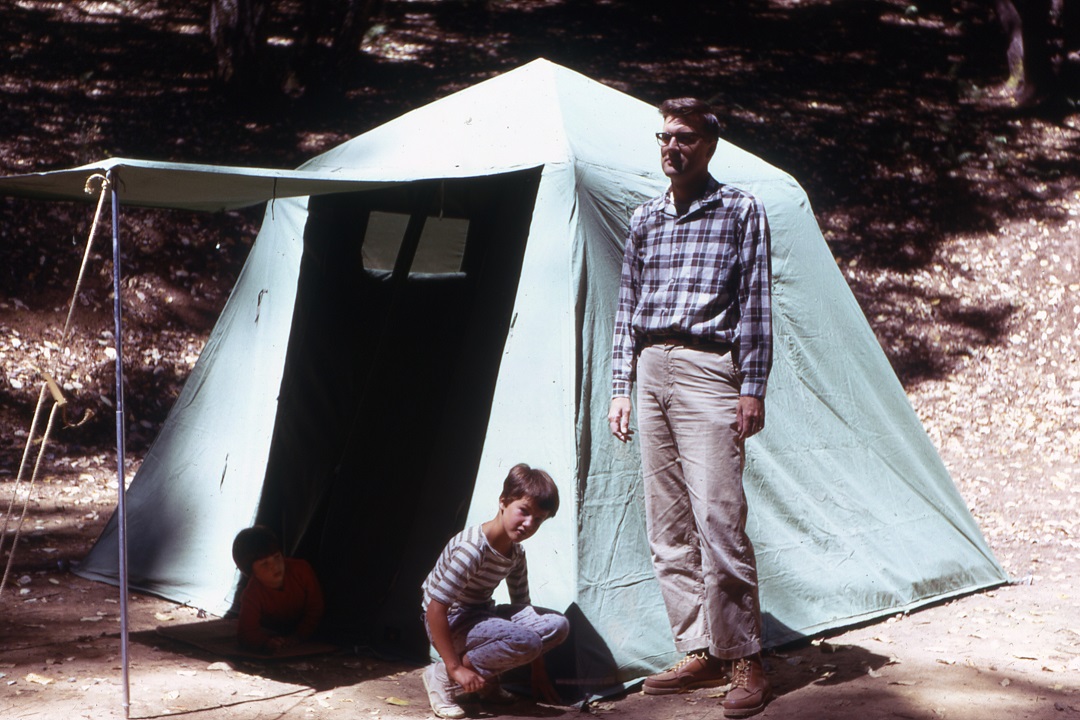

Grandmother had lived alone on her farm for almost as long as John could remember. He knew the stories about Grandfather, how he had built the porch for her to sit on in the evenings, how he had planted the berry bushes along the edge of the field when they were first married. But John didn’t remember his grandfather very well. He had been a very small boy the last time Grandfather rowed him around the island in the dinghy. Grandfather had pointed out an osprey nest on the top of a tree by the ferry. John remembered the great blue herons that leapt up out of the reeds when they rowed close to shore, but he couldn’t remember his grandfather’s face. It had been a long time ago.

Now John was almost grown up. This summer he was coming to the island all by himself, because Grandmother needed his help. Every summer of his life he had visited the island with his family, for a week or two, and sometimes in December they came to cut a Christmas tree from her woods. But this year John had come alone, and, as his grandmother had promised in her letter, starting tomorrow he would have his very own boat, with a real outboard motor, the Stella. As John and his grandmother bumped across the water on the last ferry, he fell asleep on his bench and dreamed of racing across the water, salty spray like a fountain behind, sparkling in the sun.

By the next week, John had begun to notice more changes in his grandmother. She seemed shorter, and she walked like her knees hurt when they went down to the shore. She got tired after only a little time in the garden, and she sometimes fell asleep on the porch after lunch. John wasn’t sure if he was supposed to worry about her, and he was so busy that he didn’t have time to ask questions.

John got up early each day and fed the chickens. His grandmother expected him to pick blackberries and raspberries from the huge, overgrown bushes in the back field, which scratched his arms even through the old long-sleeved shirt she gave him. He went alone into the woods to find mushrooms, picking them carefully so they wouldn’t break. John struggled to climb up over the granite ledge behind the barn and pick the blueberries that grew wild there, scraping his knees. His grandmother also needed him to help her in the garden, pulling up weeds, picking carrots, onions, baby beets, and beans, and washing everything carefully in icy water he pulled up from the well himself. All week long he worked in the garden, by his grandmother’s side, listening to her breath whistle softly. He was waiting for Saturday.

Saturday was John’s day with Stella. At first he had been surprised by how old and ugly the boat was. There had been no motor, just a couple of wobbly oar locks and some seats that gave him splinters right through his shorts. John had worked very hard, listening carefully to his grandmother’s instructions, sometimes getting frustrated at the slow job of fixing her up. He was so eager to put Stella in the water and go! But gradually, all by himself, he turned her into a beautiful little dinghy.

He scraped away the old paint, and repainted her light blue and white, and he replaced the rusty oar locks with the shiny new ones waiting in a paper bag in the kitchen. John sanded the seats and painted them with three coats. He threw out the moldy lines and cut new ones from sturdy white rope for the bow and stern. Grandmother showed him how to make special knots that would keep the boat securely at the dock but still let it move up and down with the tide.

When everything was perfect, John painted the big curly letters of her name with dark red paint on the stern. Grandmother told him that Grandfather had named the old dinghy for his first sweetheart, and John found his old stencil behind some old cans of nails in the barn. John fit the stencil carefully in place and held his breath as the beautifully shaped letters appeared at the end of the brush. Stella was a beautiful boat now, and with the smart new outboard motor they had driven to Robinhood Marina to buy, she could race across the river. John kept the old oars tucked inside the boat for emergencies. They were pale gray and the wood was smooth from all the times his grandfather had held them in his hands, but the motor was splendid, and John felt like he could fly in that boat.

The most important job John did for his grandmother was to sell the vegetables she grew and the berries and mushrooms he picked to the summer people who lived up and down the coast. Many of these people lived on tiny islands without a bridge or even a ferry, and they counted on the fresh things that John and Stella brought them. He made many stops each Saturday, pulling Stella quickly up to the deep water docks, tying her fast, and hollering up to the house. Sometimes he would put up the motor and row into a little beach for nap in the shade, but he could never rest for long. There were dozens of white and yellow houses with dark green shutters and flags fluttering and the summer people expecting him every week.

One Saturday, toward the end of summer, John was especially tired. There was so much to do on the farm now, his baskets were overflowing with vegetables and Stella rode low in the water as they set out early over the calm water. After all his stops, he pulled Stella into the cove on the back of Shelf Island, tied her to a big piece of driftwood, and lay down in the shade of the stumpy pines. The afternoon was hot and still. John ate his sandwich, drank his bottle of milk, still cold from dragging in the water, and fell asleep with his head on his canvas life jacket.

John dreamed of the sky over the ocean, first empty and wide, then filling with clouds, black and coming inland fast. He dreamed he was trapped on the island, the tide up and Stella tossing furiously at her mooring. In his dream he heard a voice, soft and raspy, a voice that was familiar but far away. He realized that Stella was calling to him, telling him something important. He didn’t think it strange that Stella could speak, because he always talked to her while they made their rounds. And he knew the many sounds she made, the way her floorboards creaked and scolded him if he stepped too close to the side, a noise like a cat whose tail’s been stepped on. Her oar locks chirped happily rowing around the cove and rattled resentfully when he forgot to stow the oars. He knew the impatient slapping sound of her bow line against the dock, telling him to hurry with his baskets. And how he loved the humming of her little motor! It was a song that buzzed through his body as they sped across the water together.

But in this dream, Stella was using words, telling him that something was very wrong. He could tell by the sound of her voice it was bad, but he couldn’t understand her meaning no matter how hard he strained. Suddenly there was a great flapping of wings, and John woke up with a start. An enormous heron was standing on the beach, her wings outstretched. The heron looked at John with black and yellow eyes and then rose off the beach in a whoosh. John watched the bird rise up and saw the sky rapidly darkening with the oncoming storm. Stella was right where he had left her, tied to a log, quiet and empty.

John jumped into the boat, freed the lines, pushed off and started the motor. Stella leapt to her job, racing across the waves ahead of the rain. John was frightened, the sky was so heavy, it was going to be a huge storm, but Stella was fast. They were soon home.

The farm was filled with a silver light, the trees tossing, the garden gate banging against the fence. John ran to the house and found his grandmother asleep on the porch. Her head lolled to one side, her arms were outstretched, resting on the gray wood of the chair. John felt the little hairs stand up on the back of his neck, and he felt like crying. The storm was coming and his grandmother was asleep!

After a moment she opened her eyes. She smiled and righted herself slowly in her chair. Together John and his grandmother looked over the river for a few minutes, watching the white edges of the waves hurling themselves up into the wind. Then Grandmother stood up and told John to check the windows upstairs. She went into the kitchen to make them supper and find the candles in case the power went out. John could hear her humming as he secured the house. He wasn’t sure what was going to come with the storm, but he knew his grandmother would know what to do, and he was sure he would be able to help her. He smiled as he looked out at Stella fastened tightly to her mooring, her trim jaunty bow turned bravely into the wind.