Mother was very insecure and depressed. She didn’t like to cook, had a maid for much her of life, didn’t know how to do laundry or iron, wasn’t good at domestic chores. She got by. Her entire life, she never drove on a highway.

She didn’t like her own looks and projected that displeasure and neuroses onto me, which didn’t help my own sense of self-worth.

Before I married I remember she told me that “sex wasn’t all it was cracked up to be”. That was not helpful advice. She belittled and criticized me a lot. I sought out surrogate mothers for comfort and support; older cousins and friends’ mothers. Also my warm father, who eventually divorced her. Yet, when the time came that she needed assistance, I moved her to an assisted-living complex near me in the Boston area, and cared for her for the final 15 1/2 years of her life. I felt that obligation. She did teach me about commitment and follow-through.

From my mother, I learned to be a lady. I learned good manners from her (before the complete breakdown of her mental health caused her internal filter to collapse and she said anything that popped into her head; frequently something nasty or inappropriate).

But mostly I learned to love the arts from her. I took beginning ballet at the age of 7. She spent a year in New York in 1935, studying with the greats of the era, trying to be a modern dancer. It wasn’t to be, but she looked back at that time as the happiest of her life. She appreciated and encouraged my interest in acting and singing. I began talking voice lessons in 11th grade.

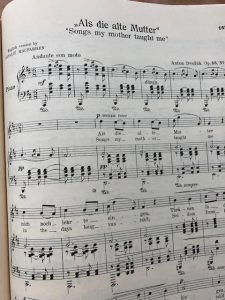

“Songs My Mother Taught Me” from the classic song book 56 Songs You Like to Sing was the first song I sang with a new teacher, a former opera singer, in 12th grade. Mother did teach me the Broadway repertoire when I was a very young child. She’d sing Rogers and Hammerstein show tunes while bathing me. She had a lovely voice and I was a quick study. I’d sing them out, full-blast, on my backyard swing each morning; “Oh what a beautiful morning”, to the amusement of our neighbors. For that, I am eternally grateful.

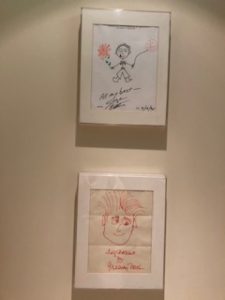

11th grade, after “Arsenic and Old Lace”; I played Elaine, the love interest. Surrounded by friends, and relatives. Mother is on the right.

I came full-circle at the end of her life, as I would sing a recital of Broadway show tunes, accompanied by the Activities Director, once my mother moved to the skilled nursing section of her life-care community. I went once or twice a year to sing for the residents. Mother just beamed. My singing finally gave her pleasure. As I was friendly with all the staff, I continued for five years after her death, until the Activities Director retired.

She took me to see the great European ballet companies when they came on tour to Detroit. My parents had season tickets to see the Broadway touring companies and would take my brother and me to appropriate shows (Carnival, Camelot, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying). The Metropolitan Opera came on tour to Detroit every year; my parents took me to one performance each season. I remember on a flight home from Brandeis one year, I noticed a man studying a score in the row in front of me. I engaged him in conversation and discovered that he would be singing in the opera that I would see the next evening.

My mother took me often to the Detroit Institute of Art and the Cranbrook Institue of Art, two of my favorite places on earth and molded my love and appreciation for the fine arts early. We dressed well. She had taste and refinement. I learned all that from her.

When it came to parenting, I did not ask for any advice from her. In fact, I tried to model my parenting after my father, who was a sweet, gentle soul, always good at listening, rather than my mother. Instead, I tried to be UNLIKE my mother as a parent. She was not a good role model. These days, I try to dwell on the good and move beyond the difficulties I encountered with her.

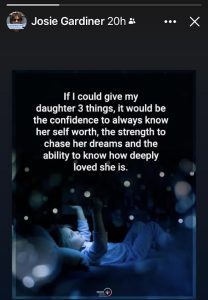

My wonderful Core instructor, Josie Gardiner, posted the above on Facebook as I wrote this story. She inspires me every day. I think her wishes speak volumes and I second her thoughts for all mothers and children.