We have a large, one-story house with a basement under most of it. About 800 square feet is finished space. The rest is broken into a series of storage and utility rooms; lots of good space, including direct entry into the garage through the laundry room.

When we purchased the house in December, 1986, the finished basement (still in it’s original form) had paneled walls, tiled floor (unfortunately, we later discovered, laden with asbestos, which we had properly removed), a large solid mahogany bar with working sink, small fridge, hidden wine racks and glass washer behind on the upper level. The lower level had a working fireplace. We were told the original owners (we are only the third owners of this home) had the room decorated like the Copacabana Night Club.

I returned to work just as we began renovations in the main part of the house. David was 18 months old. We hired a full-time nanny. She lived in this space. There was also a half bath outside the hallway. She used a guest bathroom over the garage to shower each evening. During a renovation in 1991, we turned the half bath into a full bath, but that was not the case during the time we had nannies and Dan’s sister living in this space.

It was quiet, private space with entrance through the garage. We didn’t track comings and goings. Jill, our first nanny, who stayed almost two years, was able to provide furniture – the couch, a bed, some chairs. We brought in the large, old TV.

Jill was wonderful with David, but there were other things afoot with her. I wrote about her in Jill-Sharon. Yet I was truly sorry to see her go. Astonished when she turned up working for a family in Cambridge several weeks later. As I wrote in the other story, though we had no real trouble with her, we came to the conclusion that she was high-priced call girl. She gave me two weeks notice and left all the furniture behind.

I, however, had a full-time job and had to scramble to find a new nanny on short notice. I put ads in papers (quaint, I know). I wasn’t making enough money to go through an agency (which required a huge fee). I got little traction. Eventually, I got a nibble from a college girl from Colorado who was chasing a Harvard man. They had dated the previous summer when she worked for a dentist’s wife. She was still hot for him and wanted to come back. She was already in town, staying with the family, who no longer needed her service, but she was paling around with the wife (!). The Harvard man had moved on; she was trying to lure him back. If this sounds like a soap opera…well it was. The wife gave her a good reference so I hired her. At this point, I was desperate.

She was the product of divorced parents and painted a rosy picture of getting along with both (each had remarried, and she had a little half sister whom she babysat a lot; that “happy” domestic scene was also a lie).

She needed a lot of supervision. She liked to play, but wasn’t the mature woman I had previously with Jill, who was 27. Gretchen was 19 or 20, going into her Junior year of college and underage.

On my way out one day, I, again, noticed she’d left the lamp on her end table turned on. As I went to turn it off, I noticed she’d obtained a fake ID- she had left it out on the end table (drinking age was 21 in Massachusetts). I was upset. I confronted her and told her about in loco parentis. She lived in my home, I was responsible for her. She protested – all the kids had them, besides, she was going drinking with the dentist’s wife (whose marriage was falling apart). And the Harvard guy she desperately craved wanted nothing to do with her, so she was on the make. Good grief!

I had a young, pleasant guy working in my office. I have no idea why, but I introduced her to him. The next thing I knew, he was also sleeping in my basement. If he was late coming into the office, people would look for me, “Where’s JP?” Suddenly, I was responsible for both these kids, plus my own 3 year old, all while trying to do my job.

I became pregnant during that summer and suffered from terrible “morning” (all day) sickness. The smell of her perfume set me off and I had to ask her to refrain from wearing it. She was set to study abroad at the Sorbonne in the fall. She was supposed to go home to Colorado to pack up for the trip, but her father discovered it was cheaper to fly from Boston than from Denver, so changed her plans. She was furious. She couldn’t go home to collect what she wanted to bring to Paris, or say good bye to her family. I don’t blame her for her outrage or hurt feelings. Her mother had to send all her winter clothing to my house and she had to pack accordingly. Again, she was caught in family drama. Unwittingly, I got caught too. I was the adult figure in her life; I had asked her to stop wearing her beloved fragrance. She took her rage out on me.

JP helped her pack up her belongings and the items that wouldn’t go to Paris were packed in boxes that stayed in my basement for a while, waiting for him to take them and ship them back to her home. I was sick, had “baby brain” and the company I worked for was in turmoil. I was soon laid off. I wasn’t looking through my jewelry box or wearing certain clothing items.

I first noticed my high school class ring was missing, then my father’s high school class ring. And the monogrammed circle pin my parent’s gave me for my 16th birthday. None of the items were particularly expensive. They had great sentimental value and were irreplaceable. Her boxes were still in my basement. I asked JP if Gretchen had raided my jewelry box. He looked at me with a straight face and said no.

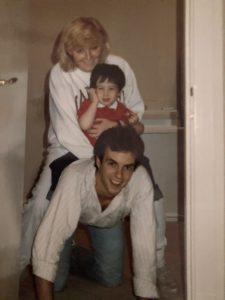

Months later I discovered a sweater purchased in Paris in 1983 was missing. That was valuable. It was cashmere with suede and leather insets, a unique piece. Here I am wearing it in November, 1985. It looks over-sized now, but it was very chic at the time. I was heartbroken. I had also been played for a sucker.

Long after the boxes had been shipped back to Gretchen’s home, JP confessed that she HAD stolen the various pieces from me. Now, he felt terrible for lying to me and apologized, but the damage was done. I thought about contacting her parents, but didn’t. Would they go through the boxes to find my little bits of jewelry? How would they punish this girl that they were already emotionally abusing? I let the matter slide. I was sad about losing my ring and pin, but my father died shortly after Jeffrey was born. His class ring was a tangible link to him that was gone forever.

Next to use the space as her home was Dan’s sister Carol, who lived with us for about 6 months in 1989. She was on-again, off-again with a guy in Washington, DC that none of us approved of. To get away from him, she moved back to Boston, came to work with Dan at Index Systems and lived with us while she saved enough money to get an apartment with friends.

Carol has always been great with kids and she was with ours. We didn’t charge her rent, but asked her to babysit on Saturday nights, which seemed like a good deal. She could come and go as she pleased, join us for meals, generally enjoy being part of the family. We loved having her around. Soon, she did move nearby with friends, but we continued to see her.

We did a huge renovation of the basement in 1991, including changing the half bath to a whole bath and putting in a comfortable sofa bed in front of the big TV screen. The surround sound system was Dan’s request for his 40th birthday. I used money I’d inherited from my father for all the renovations. Carol helped me plan Dan’s surprise 40th birthday party down in that space, welcoming guests through the garage door entrance, so that Dan would be surprised –Happy 40th!.

We enjoyed seeing Carol, even when she announced her engagement to the guy no one approved of. We all went to Washington, DC for the small wedding. David was her ring-bearer. She had two nice kids with him, but the marriage didn’t last. She moved in with her parents in Florida and followed her mother to Kansas when Gladys moved there toward the end of her life. Carol lives there today, working as an administrator at a Jewish day school. She’s always been great with kids.