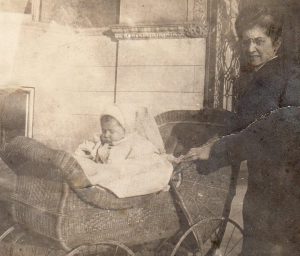

Sadie Kaufmann Guthmann on her wedding day, 1902.

By Edward Guthmann

Every year, Grandma spends the winter with us in California – in order to avoid the frigid Chicago winters and the risk of falling on ice. Even when I’m 5 or 6, she seems ancient to me.

I’m in the third grade going home on the school bus. The sun is out and kids are making the usual racket when the bus passes an old woman walking on the side of the road.

“Hey!” the boy next to me shouts and points. “Look at the midget!”

“That’s no midget,” I say evenly. “That’s my grandmother.”

True story. Grandma wasn’t a midget, but she was very, very short. When she got married in 1902, she stood 4-foot-10 and weighed 92 pounds. By the time I was growing up in the 1960s, she had shrunk and was probably 4-foot-7, 4-foot-8 at the most.

Sadie Kaufmann was born in Chicago in 1878, the child of German Jewish immigrants Simon Kaufmann and Rebecca Lehman Kaufmann. Rutherford B. Hayes was president that year. Pancho Villa, Joseph Stalin and George M. Cohan were also born in 1878, Anna Karenina was published, and Thomas Edison patented the phonograph.

Every year, Grandma spends the winter with us in California in order to avoid the frigid Chicago winters and the risk of falling on ice. Even when I’m 5 or 6, she seems ancient to me. Her skin is wrinkled and crepey, her walk is slow and lopsided and she’s easily bewildered. Grandma doesn’t talk much during her visits – mostly because she is nearly deaf.

She wears a transistor hearing aid, which fits in a little sleeve and clips to the bra strap under her dress. A thin raggedy wire twists upward, connecting to the plug in her left ear. This primitive device is barely functional, probably five percent as effective as hearing aids are today. When she talks on the phone, she has to hold the receiver upside down with the earpiece against her bosom.

Grandma, standing right, was 4-foot-10 at her tallest. Left to right: my Aunt Rollie, grandfather David Rafael Guthmann, my Uncle Dave, Grandma and my dad Marvin. 1919.

Given that Grandma hears so little – we have to yell for her to understand — my brothers and I interact with her very little. Her deafness isolates her, and although she doesn’t complain it’s clear that her isolation saddens and depresses her.

Even at the dinner table, where voices are close and she can read lips, Grandma doesn’t say much. Each night as we finish dinner my dad Marv asks her if she’s had enough to eat. And each night she gives the same reply — “Yes, I’ve had plenty” — and then adds a phrase in German: “Sehr gut geschmeckt.” It tasted good.

Kids are generally impatient and disrespectful of the elderly, and with Grandma my brothers and I are sometimes awful. In the mid-‘60s Granny Goose Potato Chips runs a lot of TV ads, and since Grandma’s wobbly gait resembles a duck or a goose, my brothers and I nickname her “The Goose.” Sometimes if she enters the living room, we slowly chant the name in a growly, elongated “G-o-o-o-se” that she can’t hear. If a friend visits the house and doesn’t know about Grandma’s hearing, one of us will say in mock indignation, “Grandma, did you just fart?” – loud enough for everyone but Grandma to hear – and relish the shocked reaction.

Oh, we were bad. Years earlier, when my little brother Davey is 4 or 5, my parents go out and leave Grandma to babysit the three of us. We exploit her slowness and poor hearing, her inability to catch us if we run. At one point Grandma is chasing Danny when Davey approaches her from behind and bops her lightly on the head with a dictionary. Danny and I think it’s hysterical.

Sadie K. Guthmann is a child of the late 19th century and by the time I know her in the 1950s and ’60s she feels displaced. “I don’t belong in this world,” she says. She can’t understand young people’s music or fashion, thinks it’s unhealthy that I spend hours watching television in the afternoon when I could be outdoors playing ball. Does she yearn for a world that was simpler, quieter? Do young people seem more reckless and rude than they were in her day? Probably.

Grandma has very little to keep her busy or engaged. She doesn’t read much because the type in books and newspapers is too small. Most TV programs are “silly” to her, the big exception being Family Affair with Brian Keith as a bachelor uncle raising three orphans (she adores it). She has no friends she could visit or meet for lunch.

She wants to help my mother with dinner, but she’s not steady on her feet. Mom feels bad for her and asks her to dry the dishes, thinking it will help her to feel useful — but Grandma’s eyesight isn’t good and the dishes get half-dried. The only cooking she ever does are matzoh balls (dense and flavorless) and an apple-and-cinnamon pastry called Apple Charlotte (very sugary, not bad).

Mostly she naps and goes on walks. Once or twice a day Grandma dons a woven-straw sun hat that ties under her chin and then flattens into a half-moon when she takes it off. She wears a coat or a cardigan, heading off through the neighborhood in her lopsided but stoic, determined walk. She always wears a dress. Not once in her life has Grandma ever worn pants.

As she walks she issues a little tune of sorts, barely audible, that seems to establish a rhythm and propel her forward. It’s the same soft, three-count whistle you hear as she walks through the house: “Phoo-phoo-phoo, phoo-phoo-phoo.” Like The Little Engine That Could: “I think I can, I think I can.” Sometimes if she starts to stumble, she laughs and says, “Look at me, I’m shikhur” – the Yiddish word for drunk.

During her three-month visits, Dad takes Grandma once or twice to temple for Friday night Shabbat services. She wears her best knit dress, her girdle and stockings, her heavy black old-lady shoes. She applies lipstick and rouge, brushes her wispy hair and corrals it in a hairnet. To complete the ensemble, she brings out her ancient fox-fur stole, its taxidermied head and legs still intact.

Grandma likes going to temple. She doesn’t know anyone, but given that she grew up with devout parents and volunteered at Temple Emanuel in Chicago where she ran the ladies’ sewing circle, Grandma brightens at the opportunity to reconnect with tradition. She especially loves the music. Her hearing is terrible, but the liturgy is familiar enough that once she catches a few notes she jumps right in — singing louder than the rest of the congregation, two or three beats behind. People turn and glance with slight, indulgent smiles.

Grandma likes going to temple. She doesn’t know anyone, but given that she grew up with devout parents and volunteered at Temple Emanuel in Chicago where she ran the ladies’ sewing circle, Grandma brightens at the opportunity to reconnect with tradition. She especially loves the music. Her hearing is terrible, but the liturgy is familiar enough that once she catches a few notes she jumps right in — singing louder than the rest of the congregation, two or three beats behind. People turn and glance with slight, indulgent smiles.

Only Dad knew Grandma when she was younger, when she raised three children in a modest Chicago flat; when she washed the family’s laundry by hand (“That was a big event in our household when Mother got a washing machine”); when she baked the bread and rolls and created a dinner each night on the meager stipend my stingy, autocratic grandfather allowed her.

“Mother never talks about my father any more,” Dad says one day, and seems saddened by it. My grandfather, who died in 1953 when I was two, is rarely mentioned by anyone and only much later do I get a sense of who he was and how my grandmother, in the language that’s become commonplace since her death, was oppressed by him.

“I think he was harsh and not so easy to get along with,” Aunt Rollie said many years later. “He was very, very strict.”

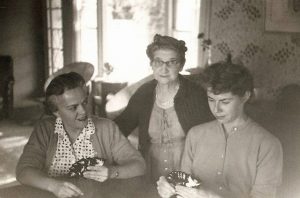

Grandma at our West Covina house. My mom Roberta and our neighbor Betty Blakeney playing cards. 1958 or ’59.

“He had a terrible temper and would hit me from one end of the flat where we lived to the other end,” Uncle Dave told me once, choking back his tears.

My grandfather drank a lot, I later learned, and according to Dad would freely spend money at a neighborhood tavern while limiting Grandma’s allowance. “He was so damn tight all the time. Mother wanted to do this or that and she had such a problem. He was always moaning or groaning.”

I couldn’t appreciate this at the time, but I lost a lot by having a grandmother who couldn’t hear. To a great extent she withdrew because of the difficulty of communication. Due to that and my own self-involvement, I never really got to know her — which makes me sad, since she was the only grandparent I knew. One year during her annual visit, I asked her questions about her early life, partly out of curiosity and partly because I sensed she’d appreciate the interest. I wish I’d recorded it, because all I remember is her saying she quit school after the eighth grade (“I was very foolish”) and went to work for her father.

What else might I know if I’d taken more interest? How she met my grandfather? What Chicago was like when she was growing up in the 1880s and 1890s, before the automobile? What prejudice she experienced as a Jew?

Grandma died in 1972, four months shy of her 94th birthday. She was greatly diminished at the end and spent her last two years in a nursing facility near my parents. My mother visited her every day at the Clara Baldwin Stocker Home, and after a while Grandma believed Mom, her daughter-in-law, was her birth daughter. “Roberta, how many children do you have?” she once asked. And every day the same plaintive question: “When am I going home?”

I have some letters Grandma wrote me when I was small and fortunately a wealth of photographs that my father and Aunt Rollie kept until they died. I’m grateful for them but I regret, much too late, that I didn’t learn more about the stories that go with them.

I like this story for many reasons. I have recently been listening to audio books about people who lived in the era of the Grandma’s youth. Life had changed dramatically since then and it is no wonder Grandma, with the added difficulties of hearing loss and physical fragility, felt lost and confused. And, to the boys, she seemed like a visitor from a past about which they were not very interested.

The sad truth is that we don’t often catch on in our youth that the stories of the elders around us will one day provide important insights into our own ancestry, lives and times. So, we listen but we don’t record, we remember some things but only vaguely. We are left with ghost-like pictures in our minds and wish that we had listened more carefully, asked more questions and done some recording.

Edward’s story reminds me of all of this in a poignant way for I am now an elderly grandma, myself, looking at the whole thing from another direction. Ah Life!

Thank you, Edward. I always enjoy your writing!

As you know as a journalist, sometimes not having the story is the story. Here, you’ve done a great job of giving us what you remember about your grandmother and what you could piece together, supplemented by these priceless photos. In the end we have a sense of her, what she suffered yet the joy she took in her children and grandchildren, that helps to counter the lost mystery of her life. Thanks for sharing this.

Thank you, John.

This is a wonderful story, Edward, and we learn a lot about your grandmother even though you didn’t know her very well. In some ways she reminds me of my grandmother, who wasn’t deaf but was often ignored or belittled by her grandchildren. It’s lovely that you have so many pictures!

Hope we can all find another place to post our stories, I’ve enjoyed reading yours.

Thanks a lot, Suzy. I would love to find another place to post stories. Terribly disappointed that Retrospect is folding!

First of all, this is a great title! And it signals courage and a respect for your grandmother in the face of the comment that prompted it. It is just possible that you were kinder to her than you remember. But, oh, your sensitivity and generosity and honesty (as in all of your writing) is throwing us, your readers, into poignant memories of our own grandparents or great aunt and uncles.. A bit of guilt, a bit of sadness and a large dose of wistfulness. I feel that this kind of treatment of the elderly old is pretty much universal due to the self-involvement of even the kindest of children. Eddie G, your writing is so lovely and evocative. This is just the latest example of it. Thank you, dear Author.