A phone message I received from Dave, one of my roommates in a group house in 1975, led to one of my life’s most truly magical moments.

When Dave returned to the phone and told me the call had been from a “John Steptoe,” I thought my roommates were playing a practical joke.

I was living with five roommates in a six-bedroom duplex on Dana Street in Cambridge and working full-time as a day care teacher in Dorchester, a multi-racial, working-class section of Boston. I had dabbled with various forms of writing all through high school and college, ranging from leaflets about the Viet Nam War, to lyrics for song parodies performed as part of a street-theatre troupe, to humorous pieces for the Harvard Lampoon. In balancing or blending creative expression with my work life, I didn’t feel myself an anomaly among the roommates who had shared time with me on Dana Street. Claudio had worked in a bookstore but spent much of his spare time playing a variety of musical instruments until he split for Puerto Rico; Lin had started a job teaching in a public school in Boston but quit to work for five dollars a day and live in the United Farm Workers Boycott House across the river; Bill was writing song lyrics (serious ones, not parodies) while working at one of the Boston hospitals as his obligation due to having successfully filed as a Conscientious Objector to the war.

I got interested in trying to write children’s books after a few years of reading books to preschoolers and bringing groups of kids to the library regularly in search of new offerings to place in our library corner. I developed strong opinions about what books I liked, and what books were engaging for the children with whom I worked. The children in our center were from low-income families with hardworking (mostly) single parents. The largest proportion were of Black American heritage, but there were also others of Jamaican and Haitian background, one or two who were Asian-American or racially mixed, and a smattering of white kids, nearly all Irish-American. We had three white girls in my class one year, and their names were Colleen, Kara, and Kelly.

I was always on the lookout for books that showcased characters with whom the kids I worked with might identify and settings or situations that might affirm aspects of their homes and communities. For instance, I was excited to find the book, Friday Night is Papa Night (author, Ruth Sonneborn; illustrator, Emily Arnold McCully). It depicted a Latina mom and her young children waiting for the father to come home because, due to his work schedule, they only saw him on weekends. The tension builds as Papa fails to show up as planned. In the end there is a happy resolution, with the children greeting their dad way past their bedtime and joyously receiving the treats he has brought for them. This was well received in our story time.

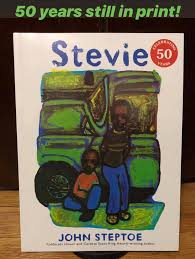

I was even more excited to discover the work of John Steptoe, an African-American author who, I came to learn, was just about exactly my age. He was a 16-year-old student from Brooklyn, attending New York City’s High School of Art and Design when he began drafting his first manuscript, Stevie. Harper & Row would publish it with his own illustrations in 1969. The book made a huge splash—because he was so obviously talented and because there were almost no authors or illustrators of color depicting scenes of life in impoverished communities of color. His first several books featured his paintings of African-American children and families in unglamorized urban settings. His characters spoke in Black vernacular, and he brought them to life as fully-dimensioned, emotionally deep characters.

From near the beginning of Stevie, here is an example of the narrator’s voice: “The little boy’s name was Steven but his mother kept calling him Stevie. My name is Robert but my momma don’t call me Robertie.”

I had found Stevie as well as his next two books, Uptown and Train Ride, in the library and put them at various times in our library corner and read them with our children. Leafing one day through a pile of Life magazines that someone had collected so that children could cut out pictures from them, I discovered a feature article in which Steptoe was interviewed and the entire text and illustrations from Stevie were reproduced in full color. (Researching this narrative, I see it was in the issue of August 29, 1969.) I carefully removed those pages and created a wall poster about John Steptoe that was on display in our classroom—a rented space in a YMCA—for at least several months.

Who could imagine, when I put up that poster, that my future magical moment (and more than a moment) would have something to do with this groundbreaking and brilliant author-illustrator?

My first effort to write a picture book manuscript came before I even worked in childcare, It was called Deedee’s Idea, and my protagonist was the daughter of a cleaning lady working and living in a castle. I never submitted it for publication. My next try was during those days working in Dorchester. I modeled the first-person voice of my protagonist—though the story was fictional–on that of a boy in my class named Greg. I had heard so many of the children with whom I worked, including Greg, talk matter-of-factly about their mother’s boyfriend or their father’s girlfriend, but I had never seen that reality represented in picture books. My Mama’s Boyfriend was my attempt to fill that gap.

Lucille Clifton (1937-2010). She won many awards, mostly for her poetry, including the National Book Award for Blessing the Boats: New and Selected Poems 1988–2000. She did not respond to the letter and manuscript I sent her in 1975.

I looked up information about submitting manuscripts to publishers; it all seemed so daunting. I had enough chutzpah that I decided I could bypass the whole messy process. Why not send my story, which I knew was great and also was so much needed, to a favorite author (or two)? The author, impressed with my talent, would then go to bat for me and help me get it published. I went to the photocopy shop, made two copies, mailing one (in care of Harper & Row Children’s Division) to John Steptoe, and the other one to Lucille Clifton (in care of her publisher). Clifton became better known over the next several decades as a celebrated poet, but at the time, I loved a picture book of hers (illustrated by John Steptoe) called All Us Come Cross the Water. Favoring full transparency, I candidly told Steptoe in my letter to him that I was also reaching out to Clifton, and I told Clifton in my letter to her that I was sending the manuscript to Steptoe. I explained to each of them that they were the best models for what I was attempting to do in my writing; in style, setting, theme, and characters, I hoped I was achieving what each of them had so successfully shown the world how to do.

Some weeks passed. It was a Saturday night in the winter, and I was staying over at Joey’s mother’s apartment. Joey was a boy in my day care class. Rhonda (I will call her) had responded to an invite for parents to join our class on a field trip to pick apples at an orchard back in October. After that, she and I began dating.

I called home to check for messages, and Dave answered the phone. It turned out that someone had in fact left me a message. Dave had gone to MIT and worked in computer science. In fact, he had written the software that controlled all the traffic lights in Worcester, Massachusetts. Dave was always precise. He wasn’t going to give me anything off the top of his head; he left to find the piece of paper where he had written down what he said was an unfamiliar name and phone number.

When Dave returned to the phone and told me the call had been from a “John Steptoe,” I thought my roommates were playing a practical joke. I pressed him on whether he had heard me talking about sending my manuscript out a couple weeks earlier. But he seemed to have no clue what I was talking about. He gave me a New Hampshire telephone number and got off quickly because one of the other roommates needed the phone. (There was one landline for the six residents in our home.)

I asked Rhonda if I could make a long-distance call from her phone. I promised to repay her that when the charge arrived on her monthly bill, but she said not to worry about it. I didn’t tell her the nature of the message. While she was putting Joey to bed, I telephoned my favorite author-illustrator, while seated in a mostly darkened living room, aware of streetlights outdoors.

John answered, and I could picture him in my mind (at least, a younger version of himself), thanks to those Life magazine photographs. I identified myself, thanked him for his call, and the magic began.

“I received your manuscript,” he said, slowly and deliberately. “And I read it.” He paused and then spoke words I can never forget. “And I love it.”

I told him how grateful I was that he had taken the trouble to get in touch with me and to say something so complimentary. He then said something like, “Well, I didn’t want Lucille Clifton to get to you first! I wanted to make sure I beat her to the punch!”

I was nearly speechless. He then said, “But anyway, she’s a writer, not an artist. So I figured I have more to offer an author like you than she does anyway,” At some point, he told me he was planning to show my manuscript to his editor; and did I have his permission to tell her that he would like to be the illustrator for this story?

That went beyond my most optimistic hopes—but I admit, not beyond my dreams. This was the precise dream I had when I sent him the story, that he would want to be the illustrator.

I remember very little of what I said, beyond expressions of gratitude, but I recall several snippets of what he said. He continued to speak slowly, choosing words carefully, it seemed, and in no rush to bring the call to a quick end. At one point he told me that he had received dozens of letters in the mail in the years since he had become successful; letters filled with ideas for stories, or actual stories. “But they’re mostly from people in Brooklyn who knew me growing up. They figured, ‘If Steptoe can write a children’s book, how hard can it be? Anybody can do it!’ But they’re all total crap.”

A second time, he referred to me as an “author” with whom he would really enjoy working. It was hard enough for me to even invoke the word writer about myself, To label myself as an author seemed to require an additional giant leap of faith. To have this wonderful and accomplished author-illustrator, apply it to me– this man whose photo and whose art had appeared on a poster in my classroom–was like having someone place a halo upon my head.

It turned out that John was coming to Boston soon to receive an award. We would plan to meet up in person and talk some more. After another phone call, we not only met up, bu he accepted my invitation to spend the night at our house at Dana St., since one of my roommates would be away. He preferred it to staying at the hotel his agent had arranged for him.

He would soon move back from Peterborough, New Hampshire, to Manhattan, and I would visit him in his apartment on Riverside Drive. The apartment was also his studio, so I got to see the very original and compelling artwork he was developing, for the book Daddy Is a Monster…Sometimes. He handed me (and signed) a pre-publication print of one of the illustrations from that book. I still cherish it and have it on display.

It turned out that I met John at a turbulent time in his personal and professional life. John and his wife would break up around that time—or maybe they already had, by the time I met him. He began exploring his bisexuality. And he was having a hard time meeting deadlines for the projects to which he was already obligated (in fact, he was way past the deadlines), Thus neither his editor nor his agent ever allowed him to think seriously about getting involved as the illustrator for my manuscript.

It turned out that I met John at a turbulent time in his personal and professional life. John and his wife would break up around that time—or maybe they already had, by the time I met him. He began exploring his bisexuality. And he was having a hard time meeting deadlines for the projects to which he was already obligated (in fact, he was way past the deadlines), Thus neither his editor nor his agent ever allowed him to think seriously about getting involved as the illustrator for my manuscript.

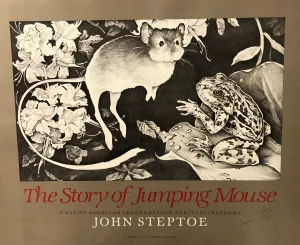

A dozen years later, John would be one of the many creative artists (especially in New York City) who would develop AIDS during that terrible pandemic. But that was after gaining even greater stature in the world of children’s literature. His art continued to become even more glorious and captivating, while in content he shifted from the urban realistic fiction of his early career to embrace the retelling of folk tales. He won awards for The Story of Jumping Mouse, a retelling of a Native American tale, and for Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters, an African tale.

He was only 39 at the time we lost him from AIDS in 1989. I had not been in touch with him for a number of years; I always wrongly assumed there would be many future opportunities to reconnect.

Two of John’s books (including Daddy Is a Monster) featured likenesses of his own children, Bweela and Javaka., They appeared as characters in the narratives (as did he, as the Daddy), bearing their actual names. Javaka would go on to become a children’s book illustrator (and eventually, author) himself.

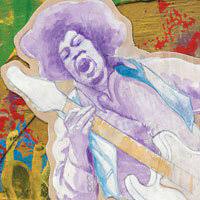

When I was teaching Children’s Literature at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, I always introduced my students to the work of John Steptoe. I also introduced them to a splendid book published in 2010 called Jimi Sounds Like a Rainbow, portraying the childhood and early career of Jimi Hendrix. Its author is Gary Golio and the illustrator is Javaka Steptoe. Some of the spectacular illustrations make you think that you have been trapped inside the guitar sounds of Hendrix!

The affirmation from Steptoe did not lead to a breakthrough in my career. John was candid with me in the ensuing months about the difficulties he was having meeting his obligations, and that he was not going to able to bring my manuscript to life or help me to get it published.

I did get my first children’s book published a few years later (1980), but it was Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold, not My Mama’s Boyfriend. That book turned out to be the beginning and the ending of my career as an author of children’s books (at least, until my next one appears).

One might say of my contact with John Steptoe that “nothing came of it.” What I believe still to be a good story remains unpublished. But that does not reduce the sparkle or the spark of that experience of affirmation. All I have to do to feel it again is to recall that amazing telephone conversation, sitting in a darkened apartment on a winter’s night in Dorchester.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Dale, of course I thought your connection with John Steptoe would result in that book being published. I’m sure that’s where you were leading us. But even though it didn’t work out, it was still a magical moment or series of moments.

Yes, Suzy, I’m happy that you appreciated the magic of that episode, regardless of the outcome in terms of publishing.

Wonderful story Dale!

Altho I was a YA and not a children’s librarian of course I know the sensitive and beautiful work of John Steptoe.

Altho your book collaboration with him wasn’t to be, so much came from your relationship – and so much to treasure.

Wonderful. “…the sparkle or the spark…” — nice.

Thanks!

What a magical time, Dale, and even though that particular book wasn’t published, the validation that John Steptoe gave you was amazing. I’m really glad for you that you got to meet him.

True magic, Dale — the kind that doesn’t always have a neat, perfect ending — and nicely told. And I also know of John Steptoe and his magic through my involvement with Bank Street College (and its wonderful bookstore).

Getting the call and confirmation from John definitely qualifies as magical, Dale. And then meeting him, having him stay with you…perfection. You got to meet someone you truly admired. It is too bad your book didn’t pan out, but that doesn’t deprive this story of the magic of the moment.

Thanks for including all the pictures of the books and illustrations–I wasn’t familiar with John Steptoe and it sounds like we lost a really talented person too early. It must have been truly overwhelming to have him respond to your letter in person, and with such enthusiasm and praise–a magical moment indeed. And then getting to know him a bit–wonderful. Even if your book never got illustrated and published, you still scored.