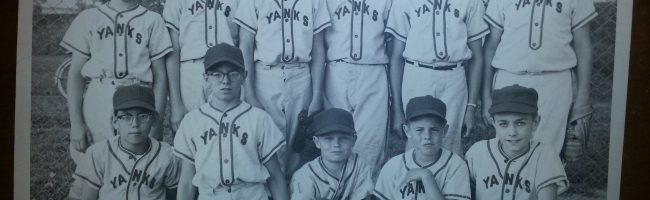

A group photo of my Fall Creek Little League team from the north side of Indianapolis in the summer of 1960 evokes a cavalcade of memories and reflections. It gives the lie to any assertion that group photographs, as a genre, are stiff or staid or a matter of meaningless formality. This one helps me to recapture the social world I inhabited at the age of 10. It also conjures my father, the team’s coach, at a much younger period (age 40) than I generally picture him. And it deepens my appreciation of a question he posed to me a few years before he died.

I received the photo just a few years ago from Gordon Dunne, front-row, right. Gordon continues to live in Indianapolis and is one of a scant few high school friends with whom I have maintained contact. He sent me a copy of the picture after reading about Dad’s passing. I was not a kid who easily made close friends while growing up—often preferring to rely on my brother Leon’s more developed social skills and tagging along with his friends or relying on our mother to invite over kids whom we knew by way of their parents. I rarely invited over peers that I had gotten to know independently; Gordon was one of those few. He had come to know and admire both of my parents and remained aware of them as he stayed in Indianapolis. He fondly recalled playing on the Yanks, the team that my Dad coached.

Gordon’s family, like mine, were registered Democrats—which was not commonplace in my neighborhood or among the broader population of the affluent white suburbs of Indianapolis. While coaching the Yanks, my Dad once came home from a meeting of all the team coaches to report that another coach had been extolling the virtues of Richard Nixon—then the Vice President and the GOP candidate for President. “What I really like about him,” Dad quoted him as saying, “he reminds me of that Senator McCarthy.” This was six years after the anti-communist witch-hunting senator from Wisconsin had been censured by the U.S. Senate. Dad, a lawyer and founding member of the Indiana Civil Liberties Union, said he was so flabbergasted that he didn’t say anything. But political kinship wasn’t the reason for my bond with Gordon. I was drawn to his easygoing personality and his sense of humor.

One of the first jokes Gordon told me and other boys was during recess in third grade or so. A woman is riding a bus and has a bad headache and is searching desperately in her pocketbook for her aspirins, but having no luck finding them. “My aspirins! My aspirins!” she calls out loudly. (But in Indiana, we pronounced the word aspirin as assburn.) The bus driver calls out, “Lady, if your ass burns, stick it out the window and let it cool off!” This was a really risqué joke for me at around age 9. I always remembered it, but I’m positive I never told it to anyone.

My brother Leon and I are the two boys with glasses on the left of the front row; I am on the end, with one knee up and one down. This team would mark Leon’s final year in Little League. Note the ball in his left hand: he was a left-handed pitcher and—truly unusual—a left-handed second-baseman. (It’s much quicker to make the throw to first when you are throwing across your body from the right side.) He would become ineligible upon turning 13 in 1961. In contrast, this was my first year in the Majors. I was just one year behind Leon in school, but my December birth date put me two years behind him so far as Little League was concerned. I was 10 in the summer of 1960 and would get to play two more baseball seasons before moving up from Little League to C League.

There was a rule, at least in the Fall Creek Little League, that Major League teams should carry two ten-year-olds on their rosters. The two on our team were Tom Bushman and I. Tom is in the front-row beside Gordon. There were other teammates (including Gordon) who were going into sixth grade like me at Fall Creek School, but they were already 11 and would have just one more year of eligibility.

Tom, like me, had an older brother on the team. His brother Bill is in the back row, with his hat obscuring just a bit of my Dad’s left cheek. Dad was concerned early in the season that Tom had a weak arm and wanted him to be able to throw the ball in from the outfield. For decades, Dad was fond of quoting Tom’s response when he suggested that Tom should throw the ball around at home with his brother Bill—get some extra workouts in to supplement our time together as a team. “Why, Mr. Fink,” Tom asked, “you think Bill needs the practice?”

Two decades later, Tom and his wife would buy a house on North Park Drive just down the street from my parents. He would be one of the air traffic controllers to go on strike fighting for safer and saner conditions in the air traffic towers in 1981, and thus he would be one of the casualties of the early months of the Reagan Presidency. Bill made a complete career transition, opening a carpet-cleaning business. From what I heard, be ran the business with integrity and was much happier without the stress of the airport tower. But in 1960, we knew him only as our best pitcher. Tom and I, as the younger brothers and the two 10-year-olds, mostly got into the lineup only a few innings per game, and mostly played in the outfield, But Dad gave me a few innings at first-base, my favored position, from time to time.

I remember Gordon’s personality off the field but in truth, I do not retain any good visual images of his conduct on the diamond.

In the middle of the front row is Jeff Kuhn, a kid in my grade who was 11. The smallest member of the team but also very athletic, you could always count on Jeff to give the maximal effort at all times. He almost never struck out. And if he got on base, he could steal.

Paul Ford is on the right end of the back row. He was in my grade, often in my class at school, and also lived in my neighborhood. He was our starting center fielder. This photo shows him when he was sort of slow and strong and a little beefy; in seventh grade, his hormonal changes would turn into a track star who had no extra pounds and could outrun anybody. He would also be the first boy I knew to “go steady,” and I think it lasted all the way from seventh grade through the end of high school.

Our catcher, Brian Dixon, is on the left of the back row. Speaking in a high-pitched, almost squeaky voice, he would maintain a running commentary while receiving the pitches. “Pitcher catcher, pitcher catcher, pitcher catcher!” Meaning—don’t even think about the batter; it’s just you and me.

I don’t remember much about Brian but I do recall that his father spoke in some kind of accent, perhaps from Scotland or Wales. His father stunned me by saying that, even in the summertime, Brian had to be up by 6:30 every morning. I’m not sure if they had animals to feed or what, but most of us had the luxury to sleep later than that during summer vacation.

Next to Brian Dixon is one of our 12-year-olds, Eric Filippo. I think he was our starting first baseman. In between Bill Bushman and Paul Ford are two similarly looking boys with blondish coloring whom I cannot recognize. However, I know that one of them was named Don Scotten, and I believe he played third base. Since I haven’t named a shortstop, the other boy may have been our shortstop when Bill Bowman pitched (and he may also have played second base when Leon pitched.) I am quite sure that Bill Bowman was the starting shortstop when he wasn’t on the mound.

This brings me to that conversation I had with Dad a few years before he died. It was so unusual for him to ask for help in remembering something. In fact, I can’t put my finger on any other similar conversation I ever had with him. Typically, he not only remembered the names of all his own high school friends and college friends and men who had shops or dental offices in his hometown of Newton Falls, Ohio, and people he met during his years in the Army. He even tended to remember the names of people I talked about from high school and college as well or better than I did.

But here he was, calling one day from his law office, where he continued to work every day right into his 90s. He wanted to know if I could help him. He had been trying to remember the names of each of the players on that 1960 Yanks team—which, he reminded me, had won the league championship. He had nearly all of them all in his mind, but he was missing one. He proceeded to go through the lineup. “Brian Dixon was our catcher. Either Leon or Tom Bowman pitched. Eric Filippo was at first base…Leon was at second…”. He went right on, “Paul Ford and Jeff Kuhn” in the outfield, and I’m pretty sure he mentioned another boy, Jay Trieb, who also played outfield and isn’t even in the photo. But Dad was right; he was certainly on the team and in fact was our best base stealer. Dad mentions someone for each position, but he is missing the name of our shortstop. Over 50 years have passed, and Dad is frustrated that he’s forgotten the name of one of his Little League players. It was such a powerful moment that I even discussed this during the eulogy I gave for him in 2015.

If only Gordon had sent me that group photo a few years earlier.