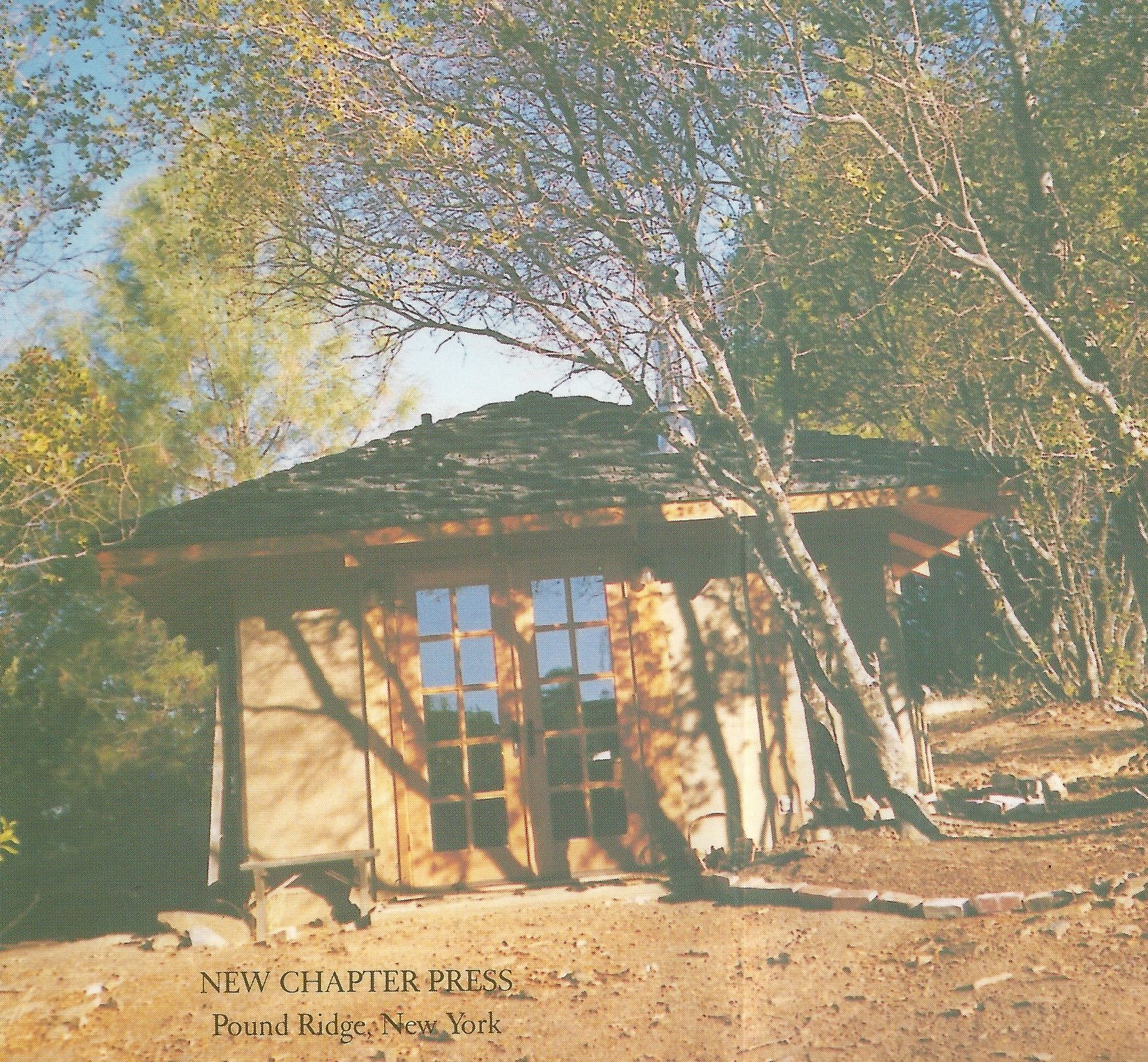

The Earth House, complete with windows. From the dust jacket.

Editor’s note: “Windows” is excerpted from Jeanne DuPrau’s poignant, lyrical memoir The Earth House. The tale begins, as another excerpt recounts, with a vague disquiet. Jeanne and her partner Sylvia learn to meditate from a teacher called The Guide, and decide to build a house made of rammed earth in a group compound in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Then life overtakes them and they try to use those insights to cope. This chapter recounts their quest to find suitable windows for the house.

I could not believe that something as tangible as carpentry could require that you deal with abstractions like five sixteenths or nine thirty-seconds.

We went shopping for windows. This meant going to places with warehouses in back and store-like areas in front where doors and windows were on display. It was odd to see doors and windows standing alone, not in walls. They became obstructions in space rather than openings, the exact opposite of what they usually are. You had to go around them instead of through them.

The friendly salesman showed us sliding aluminum windows in brown, black, and silver; large-paned windows with grids slapped onto them to make them look like small-paned windows; plain wood windows drenched in preservatives; wood windows coated with vinyl; and vinyl windows without any wood in them at all. All these windows were highly technical. They came with brochures explaining how the chemicals and vinyl made them impervious to drought, rot, and warp, though not explaining why the vinyl coating would not, after a while, begin to crack and split, making the windows shabby in a way that couldn’t be repaired by a simple coat of paint. We asked the salesman to figure up how much a plain wood window, about four feet by six feet, without vinyl, would cost. “Nine hundred forty-six dollars and twelve cents,” he said.

I fell into a foul mood. It wasn’t just that this seemed like a lot of money. Even if I’d had the money, I wouldn’t have wanted to spend it on the windows I saw in that store. The problem was, they were ugly, cheap-looking, ill-crafted, phony, dishonest windows, and the thought of putting them into what I hoped would be a simple, beautiful, at-one-with-the-environment house filled me with despair. Sylvia, who was better at keeping things in perspective, did not get as worked up about the windows as I did, but she disliked them, too.

It is a serious matter, beauty. I think the skin-deep definition is wrong. A truly beautiful object is not likely to be pretty on the outside and ugly underneath; wholeness is necessary to beauty. When you look around at the world—at the things that occur naturally in the world, that is—you don’t see much that’s ugly. Water, trees, flowers, rocks, fish, birds—all are astoundingly beautiful. If you take a couple of steps back from your human bias, less immediately appealing things such as cactus plants and boa constrictors and sinkholes full of boiling mud are also beautiful. Whoever made the ten thousand things of the world (let’s imagine for the moment that someone did) paid close attention to the fine points. No detail has been sketched in carelessly, or left out in the interests of time. Why is nature like this? Why would any craftsman be so zealously attentive to every tiny detail?

The philosopher Krishnamurti says that attention is love. That makes perfect sense to me. This world, which is so beautiful, which displays infinite attention to detail, must grow out of love. Then does ugliness come from lack of love? Certainly one reason we have ugly aluminum windows is that the manufacturers can make a lot of them easily and cheaply. The only love in that is the love of money. Look behind nearly every ugly thing and you will find that it was made with a dead indifference, or with the hope of gain. Making a beautiful thing takes time, attention, and care. That’s what I wanted in the windows, so they would match the rest of the house.

I explained the problem to the Guide. “Why don’t you make your own windows?” she said. I smiled tolerantly, thinking this must be a joke. I have no skill at woodworking. Once I tried to make a toilet paper holder with a flat piece of wood, a dowel, and a drill, and the result had to go into the firewood pile. But she meant her suggestion seriously, and I could see no alternative. Maybe, I thought, Sylvia would be good at woodworking. She had made our outdoor shower floor, after all; and she’d done other things that, while not exactly carpentry, were more or less in the construction field: she’d painted the entire outside of the house one summer, all by herself, and she’d installed a drip-watering system in the garden. This was evidence of a sort of handyman inclination, I thought. “Do you think you might have a talent for window-making?” I asked her. She didn’t know. She looked doubtful. But she was willing to give it a try.

We signed up for a woodworking class at the local high school. June, another member of the Center, enrolled with us. She had some experience with wood, having made meditation benches for meditators whose legs would not fold.

We signed up for a woodworking class at the local high school. June, another member of the Center, enrolled with us. She had some experience with wood, having made meditation benches for meditators whose legs would not fold.

The class was held in a drafty box of a building with barn doors on the front and machines inside that had the look of dinosaurs, their jaws and fangs frozen in the moment before they closed down on their prey. Sawdust covered the floor, and the place smelled like oil and hot metal. The teacher explained each machine and told us how to work it. I fought a desire to go right home. Each time he turned on one of the machines it made a hideous screech or roar or whine. You had to wear earplugs against the noise, and then you couldn’t hear what anyone was saying. Many people in the class had taken it before. They were taking it again only to have access to these tools. They were making advanced things like laminated tabletops and cabinets and futon bases.

We told the teacher we wanted to make windows. He looked interested, in a skeptical way, and said we should go to the library to find books about windows, and also to a junkyard, where we could buy the sort of window we wanted and take it apart to see how it went together. We went to a salvage yard down by the railroad tracks, where the piles of junk were like a small mountain range, in the middle of which was a tiny shed, where an electric fan blew air on a fat man in overalls. From him we bought an old window that was just barely not falling apart.

To make a good window, you have to keep a visual image of the finished product in your head for constant reference. Otherwise you end up with pieces of wood that will fit together properly only if you turn them upside down or backwards. Sylvia had trouble with this. The image in her mind kept dissolving when she wasn’t looking at it and reassembling itself in faulty ways. “I can’t do spatial relationships,” she said, after having drilled some holes in the wrong side of the frame. She confined herself mostly to tasks that did not require visualization, such as fetching the T-square from the tool closet.

My problem was with precision. It seemed to me that the smallness of the lines on the ruler between the quarter-inch marks was an indication of their lack of importance. I could not believe that something as tangible as carpentry could require that you deal with abstractions like five sixteenths or nine thirty-seconds. When the marks on the ruler seemed too small, I put my pencil line where my intuition told me it should go. The consequences of this technique were occasionally out of all proportion to its harmlessness, as when, for example, a hole and a peg missed each other by a sixty-fourth of an inch.

Once you’ve cut the pieces of the window, you have to put them together so that they are at exact right angles and stay that way rather than relaxing into parallelograms. This requires you to make joints where two pieces of wood come together. We studied joints in the books we’d found in the library. There’s the mortise and tenon joint, the rabbet joint, the dovetail joint. On paper they look simple. You make a sort of peg on this piece of wood and a hole for it to fit into on that piece. In practice this is hard because you need special tools to do it. You need a router with a certain kind of bit, a drill with a certain kind of jig, a saw with a certain kind of blade, and our workshop was equipped with only one of each of these.

We spent quite a bit of time in wood class waiting for someone else to finish using the tool we wanted. Someone who was making forty-two slats for his laminated tabletop always got to the saw ahead of us. The floor of the wood shop was cement; standing on it for two hours made my back hurt, but there was nothing to sit on except the stools at the work tables, which were occupied almost all the time. Also, of course, you couldn’t have much of a conversation while you waited for the saw or the router, because there was too much roaring and screeching going on. My dearest memory from those evenings of woodworking is of Sylvia leaning against a table, with her arms folded, wearing ear protectors that were like large old-fashioned headphones and looking wanly down at the sawdust on the floor.

Wood class lasted eight weeks. By the end of that time we had measured and cut four boards for the frame of our first window, a practice window that was to be a model for the real windows we would make later. We had drilled holes in these four boards and put them together with dowels, an easier method than making the joints, and the result was the final product of our two months of work: a nice wooden rectangle.

We also learned many valuable things. Sylvia and I learned that we disliked woodworking a great deal and were not good at it, and June learned that she liked it well enough to volunteer to make our windows for us, which she did, lavishing upon them time, attention, and care. They were beautiful. This is how learning woodworking solved the window problem, proving the Guide right, as she so often is.

Jeanne DuPrau is a writer of fiction and non-fiction for children and adults. She is best known for The City of Ember, a New York Times Children’s Bestseller, and its three companion books, The People of Sparks, The Diamond of Darkhold, and The Prophet of Yonwood. The Ember series is read by children from the age of ten on up and often by adults as well. It was made into a movie starring Bill Murray in 2008. Jeanne is also the author of a young adult novel called Car Trouble, a memoir called The Earth House, several non-fiction books, and various essays, book reviews, and stories.

I love your description of keeping the visual image of the finished product in your head for reference and Sylvia couldn’t do that. You describe everything so beautifully; I can hear the sounds and smell the smells perfectly. Lucky for you, June was better at woodworking than you or Sylvia and was willing to make your window frames, as well as becoming a constant friend.