[Disclaimer: I acknowledge the similarities to Tom Brady are too great to simply ignore. A retired superstar, despite all prior protestations, simply cannot resist the opportunity to return to the field of his great triumphs just one more time to go for the gold. So, too, when I saw this week’s Retro prompt, and given my experience both as a litigation attorney who often dealt with juries and as a long-time resident of New York City (where no one – and I mean no one — is exempt from jury duty), I just had to write one more story this week. But that’s it. Honest. I’ll just see everyone at the Retro Hall of Fame induction ceremonies.

* * *

I trust everyone reading this who knows me at all will take the above disclaimer for the tongue-firmly-in–cheek bloviation it was intended to be. I also know how lawyers so often go on and on with their professional war stories, despite the stories typically being more interesting to them (and their egos) than to their listeners. So, in consideration of this, I have chosen just four jury adventures – two as a juror and two as a lawyer – and have reduced them to very abridged, bullet-pointed mini-stories. Not exactly RetroFlashes, but I guess you could call them “lawyer’s briefs.” Any curious and/or masochistic reader who wants to hear more of the details can contact me, preferably with the offer of a drink in exchange.

Here they are:

The Automobile Accident Case Where I Was Chosen Foreman of the Jury

-

- * I shouldn’t have been allowed on the jury in the first place because I was a lawyer.

- * I certainly shouldn’t have been chosen foreman by the other jurors; see above bullet point.

- * As a lawyer, I knew with about 95% certainty that the only automobile accident cases that go to trial in New York are not really between the parties involved in the accident, but are being pursued by their respective insurance companies because they couldn’t reach a settlement. (The parties are required by their policies to cooperate with their insurers.) Jurors should not know this fact.

- * In fact, I was able to convince two reluctant jurors to come around to the verdict I and the rest of us wanted to reach. I am sure they were unduly influenced by the fact that I was a lawyer. This is not the way it is supposed to happen with juries. (n.b., Henry Fonda was not a lawyer in “Twelve Angry Men.) But we all got home in time for dinner.

The Federal Securities Class Action Where I Got Myself “Dinked” from the Jury Pool

-

- * The judge explained that this shareholders’ class action case would take several weeks to try. This is not unusual for such complex cases, where millions of dollars are at stake. In fact, the trial lasted several months. I simply didn’t want to spend that much time on jury duty.

- * To get myself “dinked” (removed from the jury pool) by the plaintiffs’ counsel, I made it clear in voir dire that, as a lawyer, I had a great deal of experience with class action cases. But that, as my clients had without exception been large accounting firms or corporations being sued by their shareholders, I had always been on the defendants’ side of things and had an inherent scepticism about the plaintiffs’ motives, particularly since I knew that shareholder class actions are almost always instigated by a group of specialized plaintiffs’ law firms, not the shareholders themselves. These law firms then find a few small shareholders to act as the clients and the firms typically are rewarded with 1/3 of the amount awarded to the plaintiffs by the jury (or, more likely, as settled by the parties). Again, standard knowledge for a lawyer with my practice, but something that jurors aren’t supposed to know.

- * Just to be real sure I got dinked, I also made a point of noting that the CEO of the defendant corporation (a now-defunct financial behemoth) was on the board of trustees of the museum that my then-wife was president of. To state the obvious, presidents of non-profits (and their spouses) are not inclined to tick off their generous trustees/donors. A jury decision adverse to such a trustee/donor would very likely tick him off.

- * Unsurprisingly, I was dinked by the plaintiffs’ counsel in a nanosecond of my voir dire being completed. Then I headed quickly back uptown to my office, a free man.

The Case With the “Too Perfect” Juror

-

- * When I was the General Counsel of one of the “Big Eight” accounting firms, we were sued in Minneapolis by a former bank client, claiming that we had screwed up the audit of its financial statements to its significant detriment. In the jury pool was an audit partner of one of the other Big Eight firms.

- * At first, my outside counsel was thrilled with this, figuring that the partner would be our perfect juror for many reasons. However, being in-house at my firm, I knew a bit more of the “inside baseball” among the Big Eight firms. And, as such, I knew that this partner’s firm considered itself the ne plus ultra of all accounting firms and that he might be only too willing to dump on another firm’s professionals for being incompetent hacks. So I convinced our outside counsel that, if the plaintiff’s counsel didn’t dink this guy, we should.

- * The plaintiff’s counsel, obviously fearing that there might be some sort of “professional courtesy” among the Big Eight firms and that the partner might well also be able to convince other jurors, immediately dinked the guy, so we didn’t have to use up one of our allowed peremptory dinks to do so.

- * Ironically, a number of years later, this partner’s accounting firm spectacularly collapsed. I won’t name names, but one of its biggest clients was Enron.

The Case Where I Was A Problem to the Jury

-

- * In another big bank case against my firm, this time in Sacramento, I actually had to be called as a fact witness because I had been involved in some preliminary document retention issues relating to the case. No; this was nothing like Trump and his classified documents misdeeds; it was all quite benign “chain of custody” issues, but it was not unreasonable that the plaintiff’s lawyer would want to call me to testify.

- * And my testimony was singularly dull and non-contentious. But the plaintiff’s lawyer, who was one very smart guy, kept working things into his questions to elicit from me the facts that I had grown up on the East Coast, was based in New York and had attended both an Ivy League college and an Ivy League law school. All irrelevant, but the sort of ostensible background questioning that is difficult to object to.

- * Although the case was in Sacramento, the jury was comprised primarily of elderly, white, blue-collar and very conservative residents of the surrounding agricultural area. The plaintiff”s attorney’s clear motive was to paint me as some sort of odious “Eastern elite” – and probably, without actually saying it, Jewish as well. At least that was my take on it.

-

- * And not just my take (or paranoia). We had jury consultants in court each day, monitoring, as best as they could, the jury’s feelings. (Such consultants are a standard part of big jury cases – at least if your side can afford them.) They made clear that the jurors just didn’t like me. This was also confirmed by the dirty looks one of the juror’s – an elderly lady – gave me once when we passed in the hall during the break. Of course, I could not speak with her, but her looks said it all.

- * As a result, the consultants, our outside counsel and I all agreed that it would be wise if I were not in the courtroom for the rest of the trial – let alone sitting at our counsel table. So I wasn’t, and just got reports back at the end of the day as I hung out in our lawyers’ temporary office near the courthouse.

- * To try to counter this narrative about me, our outside lawyers tried to get before the jury the fact that the plaintiff’s lawyer who had painted me to be an “elite” was himself a graduate of Stanford and Stanford Law – not exactly shabby institutions. But there never was a good moment to do this. Our lawyers were also unsuccessful in being able to inform the jurors of the plaintiff’s lawyer’s fancy Mercedes Benz parked outside of the courthouse every day. And he was careful to trade in his usual custom-tailored suits for a couple of shabby off-the-rack ones for the trial days.

- * We lost the case. No one blamed me – and we did have some “bad facts”to deal with in terms of our auditors’ work – but my presence in front of the jurors obviously didn’t help.

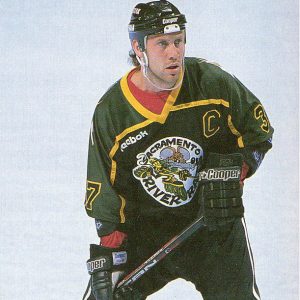

- * A few months later, when I was in a sporting goods store in New York and randomly perusing an assortment of minor league hockey team jerseys, I happened on one for a team named, unbelievably, the “Sacramento River Rats.” I immediately bought the jersey and sent it to the plaintiff’s counsel with a note that said, in full: “Dear ______, I saw this jersey and couldn’t help but think of you. Best, John.” Shortly after that, he sent me a photo of the jersey, which he had prominently mounted on a wall in his office.

Further affiant sayeth not.

Ah John, don’t tease us with only one story – come back!

And until you enlightened me I thought a dink was a pickleball shot hit on a bounce from the no volley zone intended to arc over the net and land in the opposing NVZ creating a difficult shot to return!

(Which actually sounds like a bit more fun than duking it out in a courtroom!)

Too kind, Dana, but I think this was my one appearance in an Old Timers’ Game.

As someone who has played pickleball a few times – -though I find it immensely inferior to tennis — I can confirm that “dink” is a legitimate pickleball term (as is “kitchen” for the NVZ). But lawyers have been using the term dink in the context of jury selection for as long as I can remember, albeit never to the judges, lest they consider it demeaning of the process. And, of course, one of the main purposes of dinking is to avoid too much duking later on in the trial.

John, this is fascinating (and often humorous) reading and offers your very unique legal insight. The “variables” that I mentioned in my own story are fairly obvious ones, but some of the variables you raise, and at other times imply, are often unseen or undetected by most people. Thanks for sharing this well-written piece.

Thanks, Jim. I hadn’t read your story when I wrote mine, but I am not surprised that you, too, cited “Twelve Angry Men” — and, indeed, had much more direct contact with it than I did as someone who has simply watched it a few times. And I really appreciated all your insights. I remain ambivalent about jury trials (as a defense lawyer in primarily civil cases, I usually preferred judges) but, as you note, there are just so many variables at play, both for good and bad. And getting home for dinner is not particularly good.

Wonderful story, John, as only you can write them! So glad you ventured out of Retro retirement to write it. I do remember you having that case in Sacramento, and I’m a little surprised at the type of jury you had. We are known to be one of the most diverse cities in the country (we are frequently used for focus groups about new products for that reason), and very urban, so how you got a jury of white redneck farmers is beyond me.

Thanks much, Suzy. As to the Sacramento jury, I am afraid I have to fess up a bit on that one. (If you’d buy me a drink, I’d tell you the whole story.) In fact, based on our jury consultants’ advice, our side had consciously tried to get a conservative, rural jury. They advised us that such jurors disliked banks and probably had had bad experiences with them (the plaintiff was a mega-bank, particularly in California) and, also being big on personal responsibility, they would not be receptive to the bank’s efforts to blame its problems on an outside adviser. Well, so much for that very expensive advice….

Also, thanks for the reference in your story to “peremptory” jury challenges. I have now corrected the reference in my story accordingly, and shame on me, as a lawyer, for screwing that up. Like the confusion between “moot” and “mute.”

Funny stories, but I found the fact that class action suits actually are usually instigated by law firms in order to create the conflict that they would then profit from, to be more than a bit depressing. It made me conscious of how the vast majority of us are merely helpless pawns to be played and sacrificed by people with lots of money.

Thanks, Dave. Like you, when I was first learning about class actions in law school, I perceived them as a wonderfully enlightened way for the “little guys,” with only small amounts at stake individually, to get great justice from the big, rich bad guys. That is still true to some extent — I think in terms of environmental class actions. But, once I started practicing corporate law and learning more about how class actions actually work in that arena, I felt like the guy who had gone inside the sausage factory and looked around.

Hi, John! Have missed you but respect your decision to pull back. No need ti reply to this comment — just wanted you to know.

Thanks, Laurie. Too kind and thank you for carrying on with Retro. And, of course, I HAD to reply: Retro survivor’s guilt, I suppose.

So fun to have you back, even for this one, perfect-for-you story, John. And what tales you have to tell, too. This insider story is great from every angle (I knew immediately you were referring to Arthur Andersen, who ultimately was found not guilty, but too late!). We benefitted from Andersen Consulting breaking away from them too (hence Accenture and Dan’s early retirement). Thanks for giving us your unique perspective on jury duty.

Thanks very much. Betsy. So nice to have not totally worn out my welcome with Retro stalwarts like you. And glad you liked my mini-stories.

Of course, you’re right; it was Arthur Andersen, whose longtime motto was “Think straight, talk straight,” an axiom allegedly passed on to the firm’s namesake by his mother. And its demise was particularly ironic/unfair (choose one) since, in fact, a jury did find it guilty of crimes relating to Enron in 2002. But then, in 2005, SCOTUS reversed the conviction (for some pretty good reasons, IMHO), but by then it was too late to save the firm. RIP, AA.