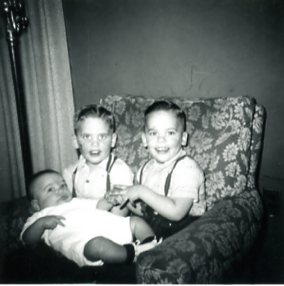

Compared to most mid-century couples, my parents married late. Dad was 34, Mom 29, and they figured they had no time to waste in starting a family. My brother Danny, born August 25, 1949, came first, and for a brief time he reigned unchallenged, the celebrated prince. For Dad, it was a long-deferred dream to have a son. I arrived 14 months later, on October 26, 1950, and when Danny’s exclusivity suddenly expired and he was forced to share the love and attention, he wasn’t happy.

Our parents expected us to be friends, encouraged a companionship that never evolved. They dressed us in matching clothes; bought toys and games we might play together; celebrated birthdays and measured our growth with pencil lines on the kitchen door jamb. But when I study childhood photos of Danny and me, I don’t see a single shot of him being affectionate toward me. I’m the interloper.

My younger brother Dave was born four years later, on July 7, 1954. An adorable kid, funny and sweet-natured, Davey became Dad’s favorite – the only son who shared his passion for baseball and the only one, for a long time, who rarely angered him. This didn’t sit well with Danny, either.

Despite our proximity in age, or maybe in part because of it, Danny and I were foreign bodies in constant collision. From the beginning we were profoundly different: in temperament, in interests, in the friends we chose and the ways we engaged with the world. He was scrappy and blunt; I was dreamy and sensitive. He liked to play outdoors, build forts, scratch and holler and rattle the status quo. I was indoors, looking at books and old movies on TV, organizing puppet shows.

Why so different? Danny’s aggression, his impulsivity and adrenaline-seeking instincts – the same qualities that later potentiate his drug use, trouble with authority and attraction to fast-moving vehicles – probably originated in the womb. In 2016 I saw a PBS documentary about the impact of genetics on risk-taking behavior, and of course I thought of Dan. Boy babies receive twice the testosterone of girls, the narrator said, and some boys more than others. “At 15 weeks, when the brain and body are crucially sensitive to hormonal changes, a second surge of testosterone occurs in the embryo and alters the regions of the brain that process fear and excitement.” Danny definitely received that extra dose.

When I was a toddler, Danny pushed me to the ground in our backyard in Chicago and my forehead hit a brick. The wound required four stitches and the resulting scar, which I have to this day, formed the letter V. For years Dan boasted that the V stood for victory – his personal mark of triumph over a weaker adversary. Later, when we were 5 and 6, I playfully grabbed him in the bedroom and said, “Danny let’s dance!” He shoved me against a dresser and once again the blood gushed from my forehead.

There was always rivalry, always resentment, but one day I discovered the strength of our bond. That summer of 1960, Danny and I spent a week at camp, sleeping in side-by-side cots in a dormitory. One day on a whim, he got on the afternoon bus that took the day campers home. True to his nature, he didn’t tell anyone he was leaving. Just before dinner, as the campus grew still and the hot August sun started to cool, I realized Danny was missing. I panicked, ran back and forth across the campus. I thought he was lost or injured or dead.

Danny returned two or three hours later, nonchalant and expressionless. When I asked where he’d gone and told him I got worried when I couldn’t find him, he shrugged. “That sounds like something you would do,” he said. And walked away.

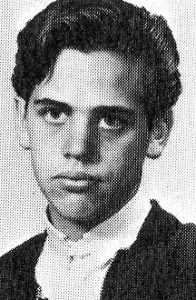

By the time he’s 13, Dan – no longer Danny – exists in his own orbit. While Dave and I go to movies together, watch the same TV shows and create a silly, hand-drawn newsletter mythologizing the neighborhood dogs, Dan grows more and more autonomous. He isn’t home much and when he is he battles with Dad, vexes Mom and treats Dave and me like pests. Two years later I start high school and Dan orders me never to speak to him or acknowledge him on campus. He’s a terror and I’m no angel, either. Until Dan gets his teeth straightened, I mock his crooked overbite. One night after dinner, our next-door neighbor Steve dubs him “Menu Teeth” because the evening’s meal still lingers on Dan’s upper and lower bite. I go to town on that one: “Menu Teeth” becomes my pet epithet for the summer.

It doesn’t occur to me that in some ways I’m as culpable as Dan in creating conflict. This is the place where memory is a rogue and incomplete, self-serving narrator: when I realize how little I know of what Dan felt about me, my slurs and sniping, my joking about his teeth and his bad report cards. Did he remember the cruelest things I said to him, or did they never burrow into his memory as his meanness did into mine?

————————————————————–

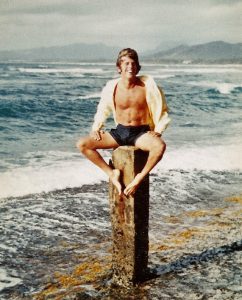

My brother Dan died May 3, 1980. He was a helicopter pilot and instructor, and after taking off with a 27-year-old student that morning, he crashed into an open field near Palos Verdes Estates. A Federal Aviation Administration investigation cited mechanical failure, with no fault on Dan’s part. All R-22 helicopters were grounded.

A death in the family makes life stand still. Everything seems embossed in sharp relief. Time is warped and surreal. People’s jokes sound callous, their voices strident. Your parents suffer an enormous loss, a haunting. But life blithely locomotes forward, unbending and indifferent.

I’m sorry Dan didn’t live a long and rich life, obviously because he deserved to, but also because my memories of him are dominated by teenage conflicts. As we got older, we reached a partial détente. In my sophomore year at Humboldt State, Dan and a friend drove up and crashed on my apartment floor. Three years later I was living in San Francisco and he visited two or three times. He was friendlier on those occasions, and we didn’t revert to competing and grandstanding. He didn’t say it, but I think he wanted to open a new chapter in our relationship. In retrospect, I wish I’d understood the olive branch he was holding out to me. I still stockpiled the slights and stings of the past, still identified as the wronged person. Unhealthy as it was, I nurtured my grudge because of its familiarity. Like a stalwart companion who doesn’t judge, it held me close.

After Dan died our parents rarely spoke about his turbulent side. “He was a good boy,” Dad said after the accident. There was something devastated but insistent in his voice – like a fist raised against a world that might think less of his son. As if he wasn’t fully convinced of that statement, but needed desperately to believe it.

After Dan died our parents rarely spoke about his turbulent side. “He was a good boy,” Dad said after the accident. There was something devastated but insistent in his voice – like a fist raised against a world that might think less of his son. As if he wasn’t fully convinced of that statement, but needed desperately to believe it.

In death, Dan became for my parents the wayward, high-spirited son who redeemed himself with a career in aviation. In the narrative they embraced, his scrambled life acquired purpose, pride, legitimacy. Instead of recalling the chaos of his teen years and early twenties, Dad extolled Dan’s later achievements. Or he’d get a sentimental twinkle in his eye and say to Mom, “Remember when Danny was 3 or 4? You made him pancakes for breakfast and he said, ‘You’re a good cooker, Mommy!’ ”

Grief is different for everyone, and in fact never stops. You don’t “get over” a death in the family. You incorporate it, you manage it. It becomes part of your experience and therefore part of you. The pain subsides but the presence of the deceased is somehow always inside you. “The past is never dead,” William Faulkner wrote in Requiem for a Nun. “It’s not even past.”

This story is adapted from Wild Seed: Searching for My Brother Dan, a memoir I published in 2017.

Edward, thanks for this insightful story about your relationship with your older brother. Having read your book, it was familiar to me, but I enjoyed reading it again. Do you think some of the personality differences between you and Dan could be ascribed to birth order? Not talking about his resentment at being displaced, or your testosterone theory, but rather the general characteristics ascribed to firstborn and middle children. Seems like they might fit.

Thanks, Suzy. I don’t know if our personality differences could be ascribed to birth order, but I do think his need for dominance is something you see a lot in the oldest sibling.

So moving, Edward.. Good writing renders the reader empathic, in this case I have to admit all the more so because of a shared experience, right down to my Dad’s, “He was a good boy.” As the last one in my family to remember my brother, I hope I’ll never “get over it.” Thank you for your eloquence. Your book remains on my nightstand…read, reread, and a reminder.

Thanks so much for your kind words, Barbara.

This was such a powerful story of your relationship with your brother, Edward. It begs the question of how much was determined by birth order and how much by a person’s innate nature. As an early childhood educator, I sometimes encountered this level of conflict between siblings who were close in age. In retrospect, there was often an underlying cause (example ADHD) that accounted for some of the behavior. I’m eager to read your book. Just ordered a copy.

Thank you, Laurie. I would guess Dan’s innate nature was more of a determinant than our birth order. Hope you enjoy the book; thanks for your interest!

A moving story and a deep analysis of what can happen to an evolving relationship when one brother dies. Your description of being invested in the idea of a “wronged person” certainly resonates, but it seems as if you let go of it. Thank you for introducing us to Dan.

Thanks, Marian!

Powerful story, well-told, Edward. I had a clear grasp of the troubles you had with your older brother and how the conflict affected you. He was also reckless and seemed to enjoy bullying you, until his adolescent years became difficult for him too. Your hindsight view of the college visits can only be viewed through the prism of what follows.

Your narrative of his death and how it changed, or didn’t, the family perspective is wise, wounded and gives the reader a glimpse into personal tragedy. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Thanks, Betsy!

Ah Edward, your tale is so beautifully, and so movingly written and so insightful.

I too lost a sibling who, like Dan had been the difficult and worrisome one, who died tragically before many issues between us could be resolved.

Thankfully my parents, unlike yours, didn’t live to see her tragic death, my sympathy Edward.

Thank you for the kind words, Dana.