Scouting was a big part of my younger years. I enjoyed the camaraderie with other Scouts, had a great time camping, and learned a number of skills that I carry to this day. In various “leadership” roles, I learned much about achieving goals, cooperation, and communication. More importantly, I developed self-confidence, learned about perseverance, and practiced life skills not gained in a classroom.

Scouting was a big part of my younger years. I enjoyed the camaraderie with other Scouts, had a great time camping, and learned a number of skills that I carry to this day.

The foregoing seems like a glowing advertisement for the (Boy) Scouting experience, which I suppose it is. But in retrospect (on myretrospect.com, fittingly), I have decidedly mixed emotions – some about the experience, but decidedly more about the organization.

I did the full gamut of Boy Scouting, starting as a Cub Scout at age 8. Girls were Brownies at age 7, which rankled me. They got to be part of their club, wear the uniform, earn their badges, and we boys had to wait another year.

I was a regular Boy Scout starting at 11, and joined an Explorer Post at 14 or 15.

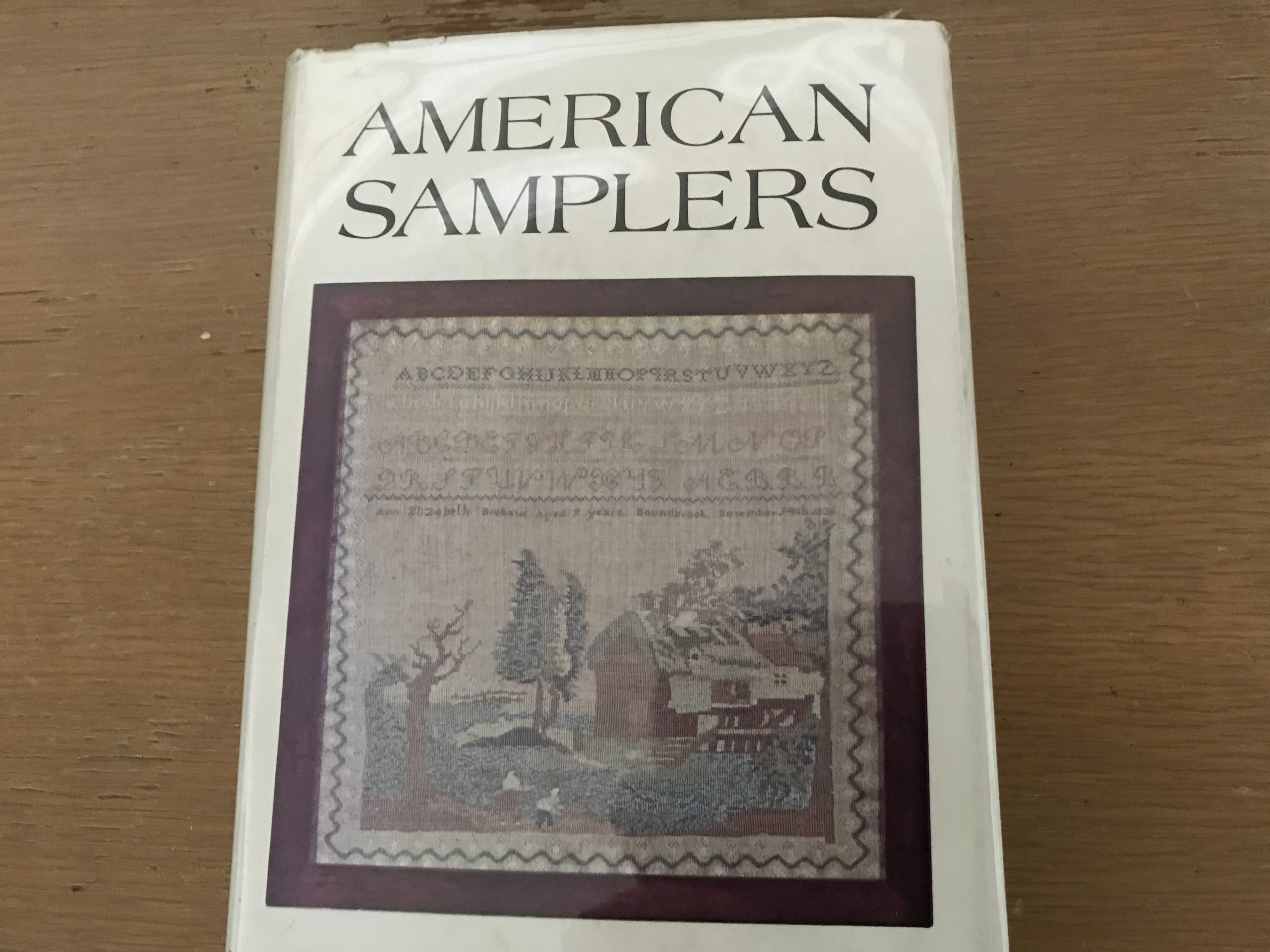

Ranks and badges were a big deal. Attaining the rank of Eagle Scout was the epitome of success, pushed by the organization, and praised by the entire community. I bought into it and got the badge in due course; ultimately it proved, to me, at least, more of an endurance exercise than anything else. After one became a “First Class Scout” the trek became a race to earn the 21 merit badges (you can see them on my sash). There were ten “required merit badges” and another eleven you could choose from dozens (now hundreds, I think) on all kinds of subjects. (I think there’s even a Horsemanship merit badge which would have been no trouble to Mr. Ed, your author). To me, they were all interesting, and we got to build and do fun things, but most (but not all) weren’t particularly challenging. Making sure you were able to schedule your time to be able to attend the classes for the more arcane required badges was more difficult, really, than the work.

After one became a “First Class Scout” the trek became a race to earn the 21 merit badges (you can see them on my sash). There were ten “required merit badges” and another eleven you could choose from dozens (now hundreds, I think) on all kinds of subjects. (I think there’s even a Horsemanship merit badge which would have been no trouble to Mr. Ed, your author). To me, they were all interesting, and we got to build and do fun things, but most (but not all) weren’t particularly challenging. Making sure you were able to schedule your time to be able to attend the classes for the more arcane required badges was more difficult, really, than the work.

I really liked earning the lower ranks – Second and First Class Scout. They included a number of outdoor activities that were terrific – a five mile hike, starting and cooking a meal outdoors without using matches, learning and practicing basic first aid, learning how to measure the distance across a river without being able to measure it directly, are high in my memory. And we all had to learn Morse code – a rite of passage for all of us. We could substitute learning semaphore, which I learned in a day, but have long forgotten it; it took longer with Morse Code, but I still remember all of the letters and some of the punctuation. Attaining the First Class Rank instilled a level of confidence that I could do a lot of things on my own without, or with only a modicum of fear. And I carry with me a catalog of knots that I still use today.

Camping was great fun. Every year we’d go for a week or two in the Sierra Nevada, hiking for ten miles or more over the several days. This brought more camaraderie and bonding with other Scouts. And since I was Patrol Leader, being in a leadership position required organizing the trip, acquiring the food and equipment we needed, making decisions about the route, and making sure we didn’t get lost. It wasn’t all fun, of course. Thirst, lousy cooked food, mosquitoes and blisters happened. I felt lucky one year to find a box of Kotex pads left by previous campers (Girl Scouts, I presumed, but maybe not) which I converted to comfortable heel pads for blisters I developed on the second day of one trip. I earned a fair share of teasing for this. I simply thought it was being resourceful.

My most satisfying merit badge (the one on the sash with a crossed axe and pick axe combination in the second row) was Pioneering. I was part of a group of half a dozen or so scouts that met for two weekends at the house of one of our adult scout leaders. It was a real challenge. We had to learn how to lash together tree branches or other poles using nothing but rope – no nails or any other aids. I can’t remember the names of the particular “lashes” but I remember they were a complete mystery to me. How I got through the first weekend, I don’t recall, but I did make the trip out into the field the next weekend where we made a small bridge across a dry stream bed. Designing the structure (very much like an A-frame) was really satisfying, and I thought at the time we could have driven a Volkswagen over it. I’m very glad we didn’t try.

My most disturbing merit badge experience was Firemanship (top row middle on the sash). It was taught by the local Fire Chief with the basic idea to learn fire safety and a bit of the science and technique of fighting fires in the community. It was a four-week class of one night a week for about an hour or two. On the second week, we were presented with a test with no preparation (the first meeting was organizational). Everyone flunked, and the Fire Chief spent the next half hour excoriating us for what he considered evident stupidity in the face of our abysmal responses. I kept my mouth shut in the face of his bullying. Had I been a year or two older, I would have challenged him for his uncalled-for conduct. So that part of Boy Scouts taught me something about people, but I do not think it was what Lord Baden Powell (the founder of the organization in 1910) had in mind.

Perhaps the most exciting (in another way) for a 14-year old boy was the Lifesaving merit badge. It was very hard to get, only because the general way to get it was to take the Red Cross course which was only taught once a year at the high school pool. What was exciting to me was pulling and being pulled around the pool by my assigned partner, a girl a year older and far more attractive than I, wearing a not too suggestive swim suit for the duration of the course. I’m reminded now of the ending of Tom Lehrer’s song, “Be Prepared:”

If you’re looking for adventure of a new and different kind

And you come across a Girl Scout who is similarly inclined

Don’t be nervous, don’t be flustered, don’t be scared

Be prepared!

(And no, the Lifesaving merit badge is not the one with the heart at the top left of the sash.)

It never got anywhere near where Tom Lehrer suggested. I was infatuated, my swim partner had no interest in me, other than to learn the proper life saving techniques!

I fully expected to be an adult leader at some point in my life. But over the years, it became clear to me that Boy Scouting far too militaristic, right wing politically, homophobic, and an organization keen on hiding pedophiles they were aware of in its leadership. My wife and I did take our son to an organizational meeting of interested boys and their parents. Our son recoiled at the militarism and thought one meeting was enough for him.

Years later, I ran into some earnest looking Boy Scouts selling something at a fundraiser in a super market parking lot. Rather than ignoring them, as was my usual wont, I approached them, told them I was an Eagle Scout, but couldn’t support them because of their anti-gay policies. One of Scouts looked straight at me and said he agreed completely with my sentiments. I still didn’t buy what they were selling, but left feeling hopeful.

Are we making progress? I hope so.