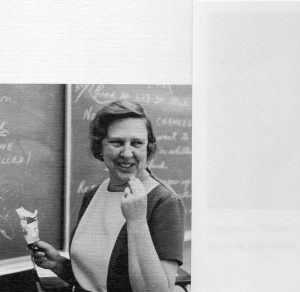

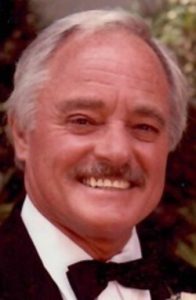

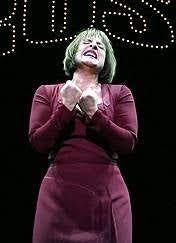

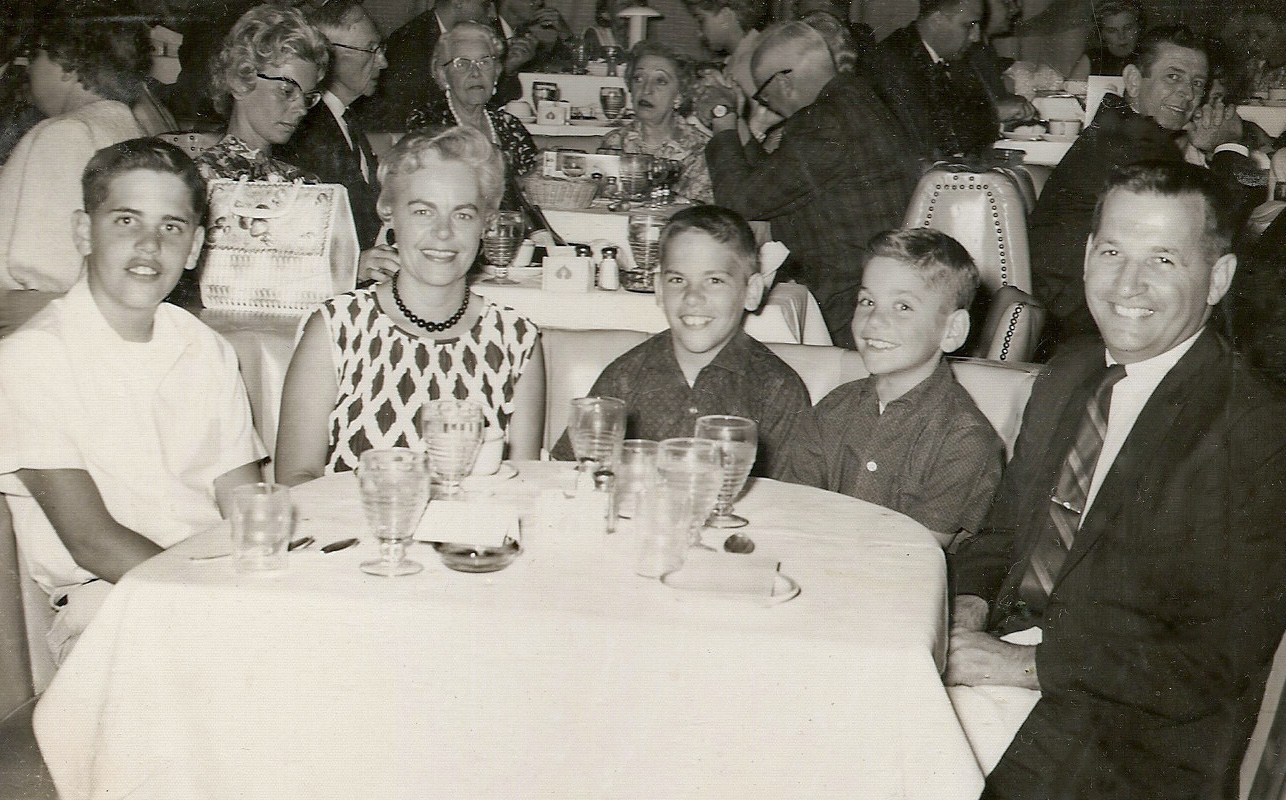

The magnificent Shirley Shaffer. Such fond memories.

It takes a long time to learn gratitude. When I look back and recall some of my schoolteachers, I’m sorry I never took the time to thank them — to let them know their hard work made a positive impact that still reverberates in my life.

I wish, sometime before she died, I had located my third-grade teacher Mrs. Shaffer. Picture a vivid personality, bright-red hair, a clarion voice, and take-charge personality. Mrs. Shaffer is an East Coast Jew, a bit of a Shelley Winters type — and therefore out of place in WASPy 1950s West Covina. She has moxie; she knows who she is.

As a kid I like her very much: She’s sassy and peppy and outspoken, but warm and caring beneath the brass. At our school there’s something called the “freeze bell” which rings loudly at the end of recess and requires students to stand completely still for 15 seconds and then walk — not run! — back to our classroom. One girl is making faces for the amusement of her friend. Mrs. Shaffer, the teacher on playground duty, quickly approaches and admonishes her. I can’t hear what the girl says in return but Mrs. Shaffer shouts back, “Young lady, it’s time you learn how to speak to your elders and superiors!” It sounds harsh and dictatorial but in the moment I’m impressed by Mrs. Shaffer’s quick comeback and command of language. It feels like a scene from a movie.

Mrs. Shaffer teaches us penmanship, and endeavors to foster a love for reading. One day she has us read a short biography of Abraham Lincoln, with the assignment to summarize it in writing for class. “Eddie, did you write this yourself?” she asks me the next day. “Yes,” I answer, a bit puzzled by the question.

“Well, it’s very good,” Mrs. Shaffer says. She’s the first person to tell me I have writing talent. I still remember how good that felt.

Fast-forward nine years. I’m a senior in high school and Mrs. Browning is my English teacher. Quiet and conscientious, she’s a totally different personality from Mrs. Shaffer but similar in that she’s all business. She’s divorced and raising two teenage daughters while teaching five or six classes a day. I get the feeling she’s lonely, was probably hurt deeply when her marriage ended.

I imagine her going home to fix dinner each night for her daughters, asking how their day went and staying up late to grade papers and write lesson plans at the dinner table. The next morning she’ll dress quickly, fix breakfast and dash off to school. She is undeviating in her professionalism and devotion to teaching.

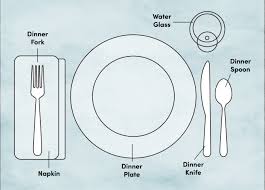

Mrs. Browning isn’t chummy. She doesn’t gossip, curry friendships with students or ask personal questions like some teachers do. Consequently, she doesn’t inspire the affection that the light-hearted, “cool” teachers do. But in retrospect, I appreciate her and know I learned more from her than from any other two or three instructors combined. She doesn’t nag or call out the slackers in class, but treats us as adults and expects us to step up and do the work correctly. She gives detailed instructions on how to write a term paper: where to type the footnotes, bibliography and index. She sets a timetable for completing each task. I miss several deadlines — it takes me years to develop a fraction of her discipline — but the example she sets never leaves me.

I never got the satisfaction of thanking Mrs. Shaffer or Mrs. Browning in their lifetimes. But three years ago when I opened a Facebook page called “You Know You’re From West Covina If…,” I saw an old photo of my seventh-grade English teacher, Mr. Nyeholt. The memories flooded in and I decided to search for him online.

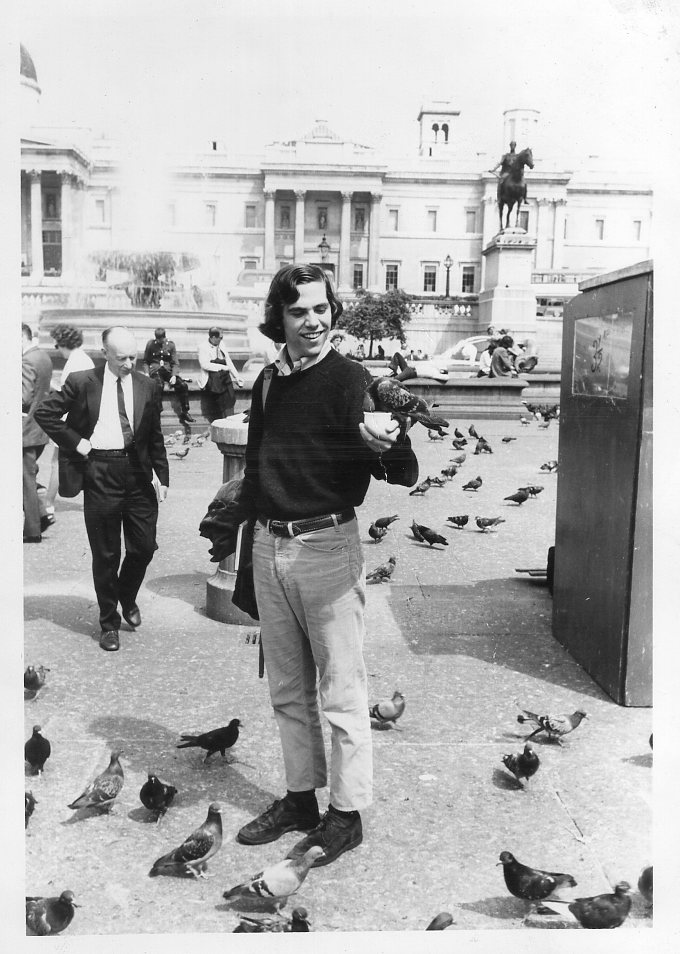

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood hadn’t aired yet, but in seventh grade Mr. Nyeholt was my Mister Rogers: someone who makes you feel good about yourself. On the surface he couldn’t have been more different: whereas Fred Rogers was plain and dweeby, Mr. Nyeholt was dashing and athletic. But in the most important way Mr. Nyeholt was similar: He had a calm, steady voice, never lost his temper and never spoke sharply to anyone. He listened, and treated his students with respect. As a result, nobody acted out in class. We’d all found a friend.

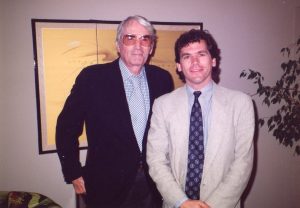

When I saw his picture in 2015, I remembered what a great guy he was. I googled his name and amazingly located Mr. Nyeholt right away. He was still living in West Covina fifty years later, and his address and phone number were online. I dialed his number.

“I’d like to speak with Henry Nyeholt,” I said when a man answered the phone. It was his son-in-law. He asked why I was calling and when I said I’d been a student of Mr. Nyeholt years ago, he stepped away to bring him to the phone. I was nervous. “Mr. Nyeholt,” I said when he picked up. “I’m sure you don’t remember me but you were my English teacher at Cameron Junior High…”

“Oh? Well, in that case you must be old!” he joked.

“I am. I found you online and I just wanted to tell you what fond memories I have of being in your English class. You were kind and you treated your students with respect. You were a wonderful teacher and I want to thank you.”

There was a brief pause. “That’s very nice of you,” he said. I think he was startled.

Mr. Nyeholt told me he was ninety one, still married to his wife of sixty six years, and had retired many years earlier. I didn’t know what to say next, so I wished him well and said goodbye. The phone call lasted three minutes at most.

The next day I emailed three friends who were at Cameron Junior High with me. When each responded and said how much they liked Mr. Nyeholt — April: “He was kind, soft-spoken”; Donna: “I appreciated him for motivating us to find an interest to study on our own all year”; Alan: “I owe him big time” — I decided to print out their remarks and mail them to our former teacher.

Two weeks later I received a letter from Mr. Nyeholt’s daughter, telling me how elated her dad was to receive the phone call and subsequent mail. That felt good. A couple of years later, I googled Mr. Nyeholt again and read that he died in December 2017. I learned he was a Navy veteran. A father of five, grandfather of ten. He taught school for thirty five years and, like most schoolteachers, he was probably undercelebrated.

There are bad teachers in everyone’s life; I had my share. The great ones are a rare and wonderful occurrence. If you have the opportunity to thank a teacher who’s still living, do it now. For yourself, and for that person whose gift will always be with you.

Once

Once