The first time I went to IKEA I was thirty-five and about ten months pregnant. I had my arm in a cast, the result of a slapstick tumble I had taken a few weeks earlier on a rain-slicked street in Astoria, Queens. I had been on my way to a piano gig at the Manhattan Grand Hyatt and was wearing a black chiffon Zsa-Zsa caftan and a parka. My belly was so huge I couldn’t see my feet, let alone the slippery wooden ramp propped on the curb. Down I went. A chorus of Greek women, concerned about the baby, surrounded me and called an ambulance. One of the Emergency Medical Technicians made a joke about needing a crane to get me onto the gurney.

"Don't worry. They have everything at IKEA. They probably even have the IKEA birthing room. Look, you've already peed your pants in a liquor store. What have you got to lose?"

The baby was fine; the arm, cracked at the elbow; the ego, deflated.

What better time for a little shopping?

“Enough of this indignity,” said my Swedish-American friend Lesley as she looked at my cast. “Über-pregnant andmaimed? This is pathetic. You are two weeks past your due date and need to have this baby pronto. A trip to IKEA is in order. Swedish meatballs are known to induce labor. They are magical.”

Lesley, who was smart, helpful, and funny in an Albert Brooks kind of way, had given birth six months earlier. She was anxious for me to join the New Mother Club.

Let me say this and get it over with: I didn’t like being pregnant. A ham-fisted, steel booted trampoline artist had invaded my previously lithe body and the ruckus drove me crazy.

My feet swelled every time I ate.

“Why bother with shoes?” said Lesley. “You could just wear the shoeboxes.”

I had tried everything to get labor started: hot baths, a tiny glass of Merlot (Lesley’s idea), awkward aerobic ambles around the block. Sex. Even swimming. My crawl stroke had become an actual crawl.

A few days after breaking my arm, I was waiting in line at the liquor store—not a good look for a pregnant woman, I know, but I was buying a bottle of champagne for a friend’s birthday—when my water broke. We grabbed our pre-packed suitcase and raced to the hospital, only to be told the imagined amniotic fluid was urine—a bladder mishap. Or pishap. The doctor sent us home to wait it out.

“Ah,” said Lesley. “The third-trimester Walk of Shame.”

Sure,I thought. I’ll try IKEA meatballs. Why not?

“What if I go into labor in IKEA?” I asked Lesley.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “They have everything at IKEA. They probably even have the IKEA birthing room. Look, you’ve already peed your pants in a liquor store. What have you got to lose?”

We drove to IKEA. I ate the damn meatballs (Köttbullar, $3.99). At that point I would have eaten a snake testicle (Rattelbals, $ 301.29) if they offered one and I thought it would speed things along.

Köttbullar aside, I loved IKEA. The whimsical Scandinavian names of household articles large and small—named after towns and people—were a linguist’s fantasy. To entertain myself I wandered through the store, inventing my own names for merchandise. In the children’s department I spotted a plastic bib (Sloppgard, $1.00), a set of tiny wooden blocks (Chöke, $2.99), and an adorable crib that would later convert to a real bed (Nytemäre, $49.99).

I was so intrigued by the living-room department I forgot about my pregnancy. I shuffled my swollen feet past affordable sofas (Näpp, $169.00) and practical coffee tables (Crapholdor, $29,99), mentally decorating rooms I didn’t own, marveling at fabric combinations, and occasionally lifting my plastered broken arm, pointing to a display, and saying things like, “Look. They even make colorful soup ladles.” (Glop, $1.39.)

Big-haired Long Island mothers pushed parade-float strollers through aisles of baby items—Bratsy, Dipewop, Spitlik—and I wondered if I would ever have my own bundle of glädje, or if I was destined to forever roam the IKEA showroom floor like a pregnant zombie, staring longingly at childproof flatware (Stabsma, $2.99) and searching for my former self (Svvelte, out of stock).

I bought numerous Slopskidtowels and a Ristsprane bookcase for the baby’s room.

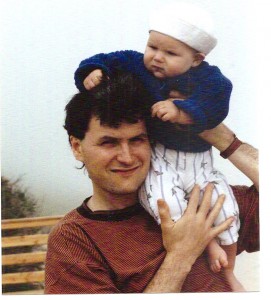

When I arrived home my patient husband wedged me into the bathtub and washed my hair, carefully avoiding the cast on my arm. He dried my back with the Slopskid, then, using the special IKEA Allen wrench, assembled the Ristsprane—the first of dozens of IKEA storage units he would build over the next few decades.

“I don’t think the baby will need a bookcase, like, right away,” he said. “This might be a bit optimistic.”

“We can store other stuff on it,” I said. “Why do they call this screwdriver thing an Allen wrench? Was it named after someone named Allen? Woody?

“Maybe Steve,” he said as he twisted the screws into place, stopping periodically to stretch his cramped hands.

I watched him, grateful beyond belief to be married to a jazz bassist willing to risk his livelihood by building a bookcase for an infant. I waddled across the room, plopped my blimpish body on the tiny sofa, and sobbed.

The final throes of pregnancy test even the strongest women.

“This is God’s way of making you ready for labor,” said a snarky friend. She was at my apartment, sporting a super slim pencil skirt and crop top, and balancing a chilled martini in one perfectly manicured hand, an unlit cigarette in the other. A year ago I had looked like her. Now I looked like four of her. I wanted to karate chop her chiseled midsection with my cast, but I feared causing another pishap. I had already peed in public once this month; a second round seemed distasteful.

“I think it’s God’s way of making me want to shoot myself,” I said. “But thanks for the support.”

“You know,” she said, glancing with obvious disdain at my IKEA bookcase. “I adore IKEA. They make such cute cardboard containers for accessories (Sluttbox, set of 3, $2.99). Maybe you could use them for baby jewelry or something.”

“It’s a boy,” I said.

“It’s New York,” she snapped. “Try to have an open mind.”

“Be careful,” said my sister, Randy. “You couldhave a very fast labor and delivery. My friend in Butler had her baby in the car, right in her pants.”

“Must have been some big pants,” my husband said.

“I feel like this will never be over,” I said.

“Well,” said my sister. “No one stays pregnant forever.”

***

A child was born. It took almost thirty hours of labor, a Philippine nurse who liked to perform selections from Madame Butterflyunder her breath, a lot of medication provided by MY HERO—an anesthesiologist who resembled the neighborhood crack dealer, and, when it became apparent the baby was not anxious to vacate a perfectly comfortable piece of NYC real estate, a C-section.

After a lot of hoopla, I was allowed to hold our son. In a heartbeat I forgot the swollen feet, the broken arm, the sore back and aching legs. I looked at him and turned into a joyful, maternal cliché.

Lesley brought me homemade soup in an IKEA container (Likuidgladje, $1.69) and wine in an IKEA sippy cup (Drönk, $1.20). She admitted she made up the IKEA meatball story.

“Well,” she said. “We had to do something to get you to the other side. Welcome to motherhood.”

***

2017

IKEA, for better or worse, has been a big part of my motherhood story. We’ve been living in Germany for twenty-three years, and have taken frequent trips to IKEA to purchase the material things that keep a household running smoothly and inexpensively.

It recently occurred to me that I’ve never purchased anything in an upscale “real” furniture store. Our modest home is decorated (quite nicely) with a mix of New York City dumpster-dive finds, antiques of negligible value from family and friends, “gotta leave town fast” spit backs from departing American expat families, dining chairs from a castle where I used to perform, and paintings from the Washington Square Art Show. Even my grand piano, cigarette-scarred and elegant, was purchased, second hand, from a jazz guy in Pittsburgh.

The rest, the stuff that glues together the ragtag pieces of our lives, comes from IKEA. The store has never disappointed me, even when I’ve been particularly susceptible to disappointment. If I’m having a bad day I stroll through the IKEA showroom, fantasize about loft beds (Krässh, €129.99) and pick up a lawn chair (Gartenswäag, €19.99), a night lamp (Elderblynd, €24,55), or a toilet brush (Covfefe, €6.39).

I have an IKEA Family Card and I always, always stop for the complimentary hot beverage (Söpewasser,free).

Our adult children have recently left home to start their own lives and careers. This year, to help them with their new apartments, we have made a record number of trips to IKEA, buying mattresses (Bäkkpadd, €119.00), dressers (Jammkräp, €54.99), curtains (Pervstopp€14.99) and dishes (Ramenscoop, set of 4, €4.00). The kids each have their own starter sets of Ristspranebookcases, lovingly assembled for them by their devoted father, who might as well keep an Allen wrench in his back pocket, just in case.

Little by little, they’ve sorted through their belongings here at home, taking what they need, dissembling their childhoods one trip to the dump at a time, until finally, one day, the shelves are empty. I enter my son’s room. It’s lonely in here, like he was never here at all. Even the smell of him is gone. My daughter’s room—now my office—seems blank without her paints and posters and piles of sweatshirts.

I guess I thought my kids would always be around—arguing, laughing, slowing us down, challenging our “fly by the seat of our pants” parenting instincts, collecting rocks, throwing rocks, watching Seinfeld DVDs, playing the “Axel F” theme on my piano, and refusing to eat eggplant.

The original IKEA Ristspraneshelf—where I once stacked cloth diapers with an arm in a cast—looks forlorn. Over the decades this shelf has held Lego cabins, school reports, Batman action figures, Harry Potter volumes in two languages, a stuffed dog named Ruby, an NBA autographed photo of Steve Nash, a replica of a Chinese Terracotta Warrior, handcrafted heart-shaped figurines, and books about Steve Jobs and Eleanor Roosevelt.

I think back eighteen years, to when our daughter was a toddler. While I was in a decorator stupor, distracted by an area rug in an unusual shade of taupe, she disappeared into the IKEA Marketplace. I raced around the showroom searching for her, sick with worry. After the longest ten minutes of my life, I found her in the lighting department with a lampshade on her head.

“Look, Mommy,” she said. “A party hat!”

Pregnancy ends with the birth of a child. Childhood ends with the birth of an adult. Motherhood never ends, but it sure seems different these days. I miss my kids. It’s a new phase for me—fraught with opportunities for redecorating, renovation, and reinventing myself. It’s a little lonely, but also a little exciting. Maybe I’ll head back to IKEA and buy myself a Sluttbox. Maybe not.

Music helps.

Sometimes your shelves are full; sometimes they’re empty. Sometimes—like when you’re pregnant—time moves too slowly, but more often it rushes by faster than the twist of a Woody Allen wrench.

I gather up a dusty IKEA basket (Weepmum, €1.19) and remember the things it once stored.

***

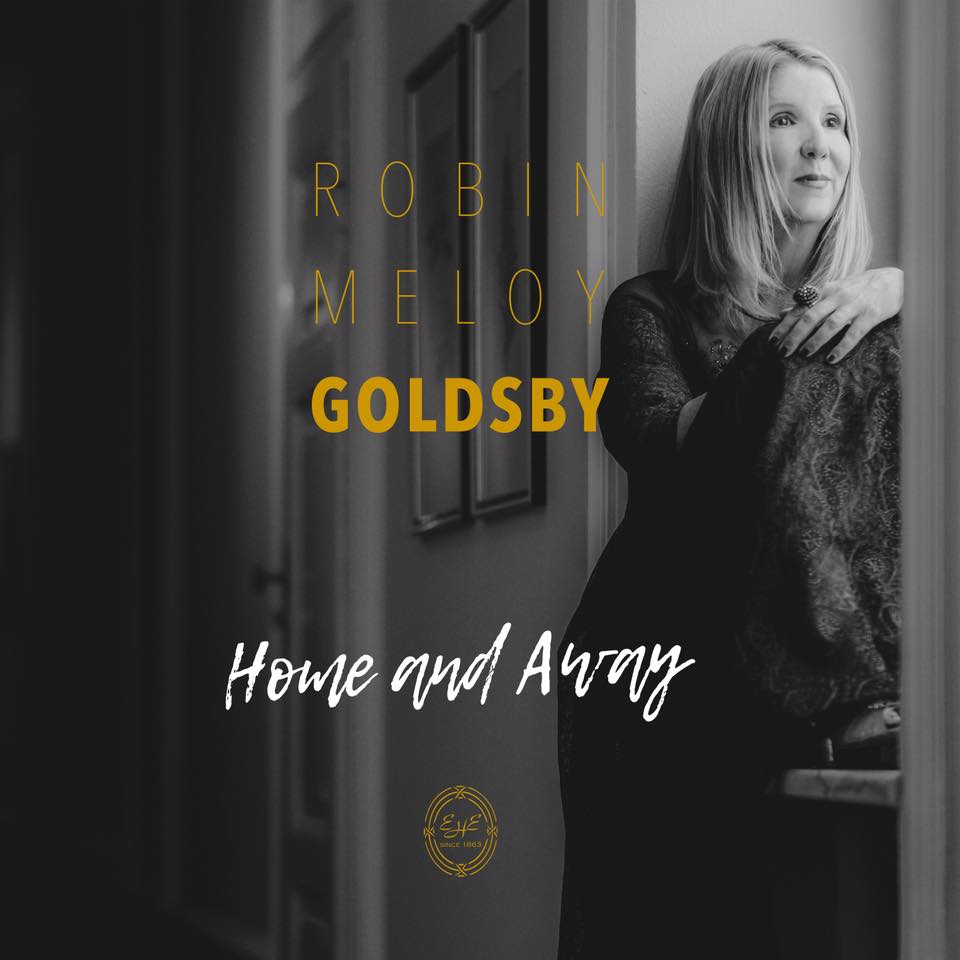

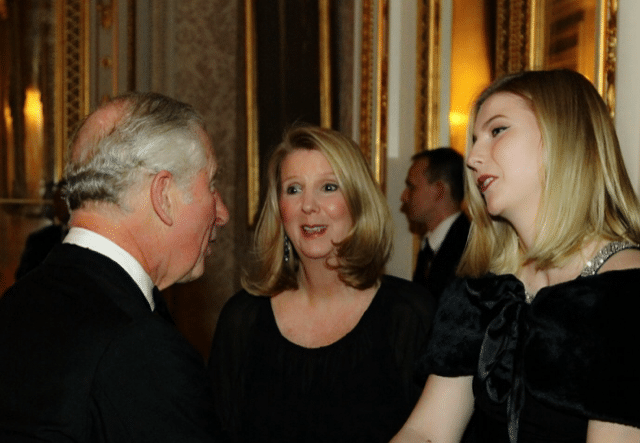

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist. She is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; and Rhythm: A Novel.

New: Manhattan Road Trip, a collection of short stories about (what else?) musicians. Go here to buy Manhattan Road Trip!

Sign up here to receive Robin’s monthly newsletter. A new essay every month!

In case you’re wondering, the German word for Allen wrench is Innensechskantschlüssel.